I’ve been following Rav Schachter’s Bava Batra shiur on YUTorah, and he recently addressed whether one may argue with the Gemara. For instance, the Gemara resolves an apparent contradiction between two Mishnayot, and you wish to propose a “better” resolution. Are you allowed to say that, including l’halacha? Rav Schachter pointed to the Rema on Choshen Mishpat 25, a siman about a court or judge who erred.

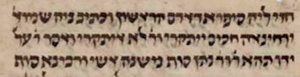

The Rema writes that one may argue even with Geonim, but not something explicit within the Gemara itself. The Biur HaGra explains: Upon the Gemara, one may not add nor subtract—all the more so, to argue. The basis is Bava Metzia 86a, that רב אשי ורבינא סוף הוראה, Rav Ashi and Ravina are the end of hora’ah (“instruction”). Rav Schachter elaborates that there was a cutoff in the type of mesorah of Torah she’baal peh from before and after that generation, so one cannot argue. I’d just add: Rema draws this from Tur (same siman), who cites his father the Rosh. The Tur writes that while the Raavad maintained one could not argue with a Gaon, the Rosh says כִּי כָּל הַדְּבָרִים שֶׁאֵינָם מְבֹאָרִים בַּתַּלְמוּד שֶׁסִּדְרוֹ רָבִינָא וְרַב אָשִׁי יָכוֹל לִסְתֹּר וְלִבְנוֹת אֲפִלּוּ לַחֲלֹק עַל דִּבְרֵי הַגְּאוֹנִים, explicitly tagging Ravina and Rav Ashi as the Talmud’s redactors. Tangentially, some of those thinking to argue with the Gemara are not as great scholars as they imagine, so it would be a bad idea regardless.

“Words of Torah are poor in one place and rich in another” (Yerushalmi Rosh Hashanah 17a), and one often needs to collect other discussions to assemble a full picture. For instance, Rav Schachter mentioned about Bava Metzia 3a that the Rishonim note that a lengthy passage/analysis was added to the Talmudic text by Rabbi Yehudai Gaon. And, one can argue with Rav Yehudai Gaon. Thus, the Talmudic text accrued some additions by Savoraim and even Geonim. (See another example in Bava Metzia 98a, where old manuscripts have the word פירוש/“to explain” before משכחת לה, and Ritva/Ramban note that until the end of the passage is Rabbi Yehudai Gaon.)

A few weeks back, Rashi argued against the Gemara’s explicit conclusion. In Beitza 33a, the Gemara concluded וְהִלְכְתָא: יַבִּשְׁתָּא שְׁרֵי, רַטִּיבְתָּא אֲסִיר, the halacha is that using dry bamboo branches as a skewer to roast on Yom Tov is permitted but moist are forbidden. Rashi explains that this conclusion, and statements of Amoraim in the sugya, are from students of Rav, who held like Rabbi Yehuda that there is muktzeh. Since we maintain like Rabbi Shimon who doesn’t hold (the same level of) muktzeh, it is all permitted. Note that Rosh disagrees with Rashi, for how could one say that Rav Ashi encoded the Talmud’s halachic conclusion against the actual halacha? Besides seeing the importance of knowing scholastic relationships, we see that Rashi, at least, would rule against an explicit gemara—though note that this is because other gemaras indicated we rule like Rabbi Shimon.

Meanwhile, a separate question is whether the setama digemara (the anonymous Talmudic Narrator) is indeed always Ravina and Rav Ashi, sof hora’ah. Some scholars say those are authored by Savoraim—the scholastic generations after the Amoraim. Others say they are even from the Geonim. (To put this into perspective, we’re used to commentaries printed in the margins, but a scribe might copy marginal notes into the main text; also, Rif and Rosh reworked the Gemara and embedded their commentary.)

Not every anonymous passage was necessarily composed at the same time. Most conservatively, an anonymous passage is (only) later than the Amoraim in the passage it discusses. Further along the spectrum, some suggest that it is all composed by Ravina and Rav Ashi, or even in later generations. As for redactors, we have elsewhere discussed whether Ravina (of sof hora’ah fame) is Ravina I or Ravina II. Furthermore, Vatican 115a/Munich 95 manuscripts have “Ashi” rather than Rav Ashi as sof hora’ah; some suggest that this was a later Savora, Rabba Yosef, a student of Rabba Tosefa’a. If so, the supremacy of an even later Talmudic text might be maintained.

This relates to our sugya in Rosh Hashanah 29b. The Gemara wonders whether one who has already fulfilled his obligation (such as blessing on bread and Kiddush on wine) may repeat the blessing to discharge someone else’s obligation. The Gemara proves, via a תָּא שְׁמַע (“come-and-hear”), from Rav Ashi’s statement that, while in Rav Pappi’s academy, Rav Pappi (fifth generation) would recite Kiddush for himself and, when his tenants came from the field, he would recite Kiddush again on their behalf. The technical term “Ta Shema” is used in interpreting/analyzing Mishnayot and Braitot and, very occasionally, Amoraic statements, by later generations who were unsure of/debating the law. Typically it is Stammaic. But Rav Ashi is the Gemara’s redactor, so let him speak for himself! This must be a generation or two after Rav Ashi. (See also Chullin 49a, which has two versions of a dispute involving Rav Ashi. This must be later as well.) We might extrapolate to other anonymous sections. If so, may we disagree?

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.