New York—First and foremost, it’s a yeshiva. But it also offers a college campus and Manhattan-based yeshiva high school education that is not offered anywhere else.

Since it opened on September 3, 1916, high school students at the Marsha Stern Talmudical Academy/Yeshiva University High School for Boys, best known as MTA, have experienced a top-notch yeshiva high school with their own instructors. In 1945, a brother school, known as Brooklyn Talmudical Academy (BTA), was founded in the Flatbush neighborhood to serve that specific community, which sought the same hashkafa and quality of education for their sons. The school later merged into MTA in 1981 and has formed a large cohort of similarly educated graduates.

However, what sets today’s (and many previous generations of the school’s) students apart is that they are offered the chance to take college courses, basically steps away on their own campus, and are offered advanced coursework, when necessary, in Tanach and Gemara, since they are also the high school division of Yeshiva University’s Yeshivas Rabbeinu Yitzchak Elchanan. “Whether it’s a top student or a student in a regular track, there are ways we can speak to each and engage them in a variety of ways that are not available anywhere else,” said Joshua Jacoby, MTA’s executive director.

“Our goal, throughout, is to maximize that student’s experience,” said Head of School Rabbi Josh Kahn. “We are centered around the student—how we can support and nurture the talmid,” he said.

Rabbi Kahn, who is midway through his first school year leading MTA, has enabled Rabbi Michael Taubes, his predecessor, to focus his energies more fully as the school’s rosh yeshiva. Rabbi Kahn’s friendly charisma and invigorating influence have already become apparent, and he knows most of the students’ names, despite his being just a half-year into his tenure. Rather than placing his office in the downstairs lobby away from the students, he made the conscious decision to move his office to the second floor, amid student classrooms.

“It’s a statement that his office is right in the heart of the school,” said Jacoby. “It’s already affected the culture of the school. It’s always been great, but I’ve had students come in to me to say, ‘School is so great this year.’ They liked it last year, but they are noticing the increase in energy,” he said. Even during the search committee process, Rabbi Kahn’s exemplary teaching skills and vitality “just blew everyone away,” added Jacoby.

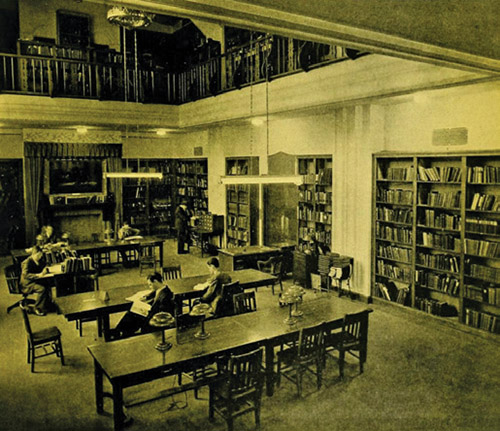

Things looked a little different in Washington Heights in 1929, when MTA first moved to Yeshiva University’s uptown campus (now known as the Wilf Campus) from the Lower East Side where it was founded. There were certainly fewer cars, but the core mission of MTA in the fall of that year remained the same for MTA this past fall. Torah studies continue to take priority in the morning, with a strong secular-studies curriculum in the afternoon. “Tradition is fixed,” noted Dr. Seth Taylor, the school’s resident historian and the principal for general studies. “The premise of the school, that Torah and Judaic studies should be in the morning, remains the same. Torah takes priority over everything else. But modernity is dynamic and changes all the time. The challenge for our school is to adapt our curriculum to the ever-changing demands of the world, while remaining loyal to tradition.”

Dr. Taylor, who has been with MTA for 28 years, is also the author of “Between Tradition and Modernity,” a book commemorating the first 75 years of MTA history.

The history of MTA is not simply an institutional history of a school, said Taylor. “It’s really about the founding of Modern Orthodoxy.” Education was at the center of the arguments and debates in the early 20th century about how Jews, who were coming over from Eastern Europe, should react to this new opportunity called America.

“We were no longer in the shtetl, we now had this opportunity to participate in the American economy; how were we to educate our children? How could we preserve our traditions while at the same time open the door to all that America has to offer?” said Taylor.

Rabbi Kahn said it was fortuitous that he has begun his tenure this year. “The centennial backdrop is the perfect paradigm for me, in the sense that a transition to a new school really is about learning the institutional knowledge of the yeshiva and getting a sense of the rich history of the yeshiva, but then being able to use that to pivot to a point of reflection and look toward the future. On a personal level, you know typically the first year as the head of school is learning. Learning what makes MTA special, what makes it what it is,” he said.

“If you look at one brick, sometimes you don’t realize it’s supporting a whole wall. So you can’t say, ‘Let me just tweak that one thing.’ Sometimes you don’t know how it interlocks with 20 other systems within the school, and how it may seem like a small detail; it really is a major part of the culture and what makes that school unique,” Rabbi Kahn said.

Together with his colleagues, Rabbi Kahn is now charged to help create and draft a vision for the school for the future. “I was not brought here for change. I was brought here for growth. The goal is to make sure that MTA is maximizing who we are; constantly focused on growing and doing what we do better.” Rabbi Kahn also chose a fascinating question of the year, which he has posed to students, staff and faculty: “If we take Torah seriously, what does that mean?” He has already collected a number of answers that have shown that the school’s current residents continue to work to understand their own identities as deeply as did those who first started the school in 1916, as well as those who joined in subsequent years.

As part of the centennial celebration, photos as well as memories have been collected, using a number of media. Current students have been hard at work compiling written and oral histories of many of the school’s living graduates. Particularly, the oral histories have been taken with the help of MTA’s Tova Rosenberg, the creator of the much-duplicated “Names, Not Numbers” program.

The centennial celebration—which is celebrating the rich history of YU High School for boys, both MTA and BTA—was launched in the school this past fall at the beginning of the academic year, and continued this past week at MTA’s annual dinner, which itself launched the YUHSB Centennial Capital Campaign, intended to raise money to modernize the classrooms of the yeshiva, room by room.

One development that has been evident at MTA over the last quarter century is that technological leaps in the outside world have been mirrored in the classroom and broadened in ways designed to enhance education. “For much of our history we were the only game in town. Over the past couple of decades, the school has gained many more competitors and we have therefore had to transform ourselves not only to the challenges presented by competitors, but also by the changing economy,” said Taylor.

The increasing impact of digital technology influenced MTA to create a STEM program, where students can develop not only a foundation in STEM and computer coding, but also a concentration in that area. “We have also developed an intensive program in writing in our freshman year to ensure our students are college ready. Moreover, we have a much more elaborate guidance department now than has ever existed in the past,” said Taylor.

Now, the school is taking the steps forward to modernize the school building on Amsterdam Avenue, in the heart of Washington Heights. The building opened its doors for the very first time in 1929 to serve the growing high school, college and beis midrash program. Ira Bernstein, a 1930 graduate of MTA who attended the dinner on Tuesday evening, was moved to the building his senior year. “His was the first graduation to take place in Lamport Auditorium, and when interviewed he refers to it as ‘the new building,’” said Jacoby.

To modernize the building, the MTA staff worked with a wide variety of stakeholders. “Over a year ago we started the process and the expert design team—who have worked with a wide array of schools across the country—came in to MTA to hold focus groups with parents, students and faculty,” said Jacoby.

The leadership spent time listening to those groups, and then worked together to build an action plan to bring the building into the school’s next century. “The goal is to maintain the incredible and rich history and legacy of the building, while innovating and modernizing for the best educational standards of today,” said Jacoby.

Aside from recruitment purposes (as almost all of the competing schools have modernized over the past decade), most important is that the modernization “will enhance the education by providing spaces that are best suited for the current trendsetting learning needs. The new layout will provide the flexibility for students and faculty to learn in a variety of ways. It’s also been proven in various studies that aesthetics go a long way in education. Just simply improving the air quality alone can provide a big difference.”

Learn more about the MTA’s centennial campaign at http://centennial.yuhsb.org.

By Elizabeth Kratz