When Andrew Burian came to America alone, after surviving the ghetto, death camps and two death marches, he tried to tell people what happened but no one wanted to listen. His landlady brushed him off. She said it was hard here, too; they had ration cards and no sugar. So he stopped talking—until his children were old enough to start asking questions.

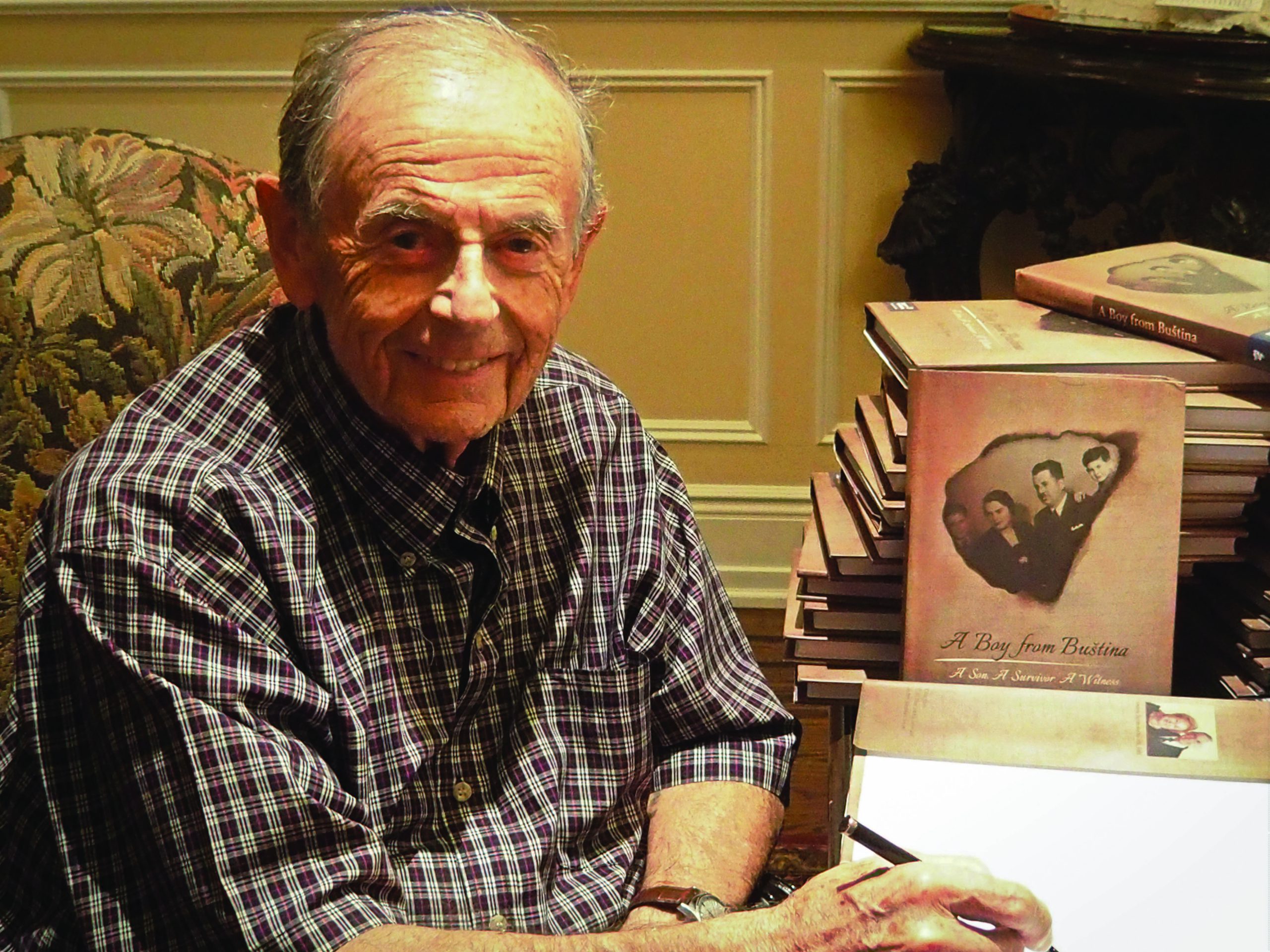

Burian began putting his story down on paper, so his children and grandchildren would know what happened, and wrote for 25 years, sometimes stopping and putting it away when the memories became too difficult. When it was finally complete, Burian’s children, Dr. Matilda Anhalt of Englewood and her brothers Saul and Lawrence, thought the memoir should go beyond the immediate family. Lawrence brought the manuscript to Yad Vashem, where he is a board member, and the book was published this summer. Burian, his wife and his children will present excerpts from “A Boy From Bustina” on Monday, September 26, at 7:30 p.m., at Congregation Ahavath Torah in Englewood, in a program open to the public.

“He never talked about it when I was growing up,” Anhalt said in an interview with JLNJ, along with her father. “As a child, I was always aware something was different. I remember asking him what the numbers on his arm were and he said, ‘It’s my telephone number.’ The story came to light in bits and pieces. There are two stories I didn’t know until I read the book.”

As he got older, Burian began sharing more of his experiences by speaking to Jewish groups and then to the schools his children and grandchildren attended, including Yale Law School, Princeton and Harvard. He has spoken at numerous Yad Vashem events such as a conference to train teachers how to teach the Holocaust in their classrooms. He recently spoke before 16,000 people at Liberty College, a Christian University, where students stood on line to meet him. “They had never seen the numbers (tattooed by the Nazis); and some didn’t know anything about the Holocaust,” Anhalt said.

“People didn’t want to hear years ago, but now they’re desperate to hear,” she said. She is amazed at the outpouring of emails she is getting since she sent out invitations to the Ahavath Torah event. “People are writing back with their own stories. There’s a need to tell and share, not just from my father’s generation but from mine as well.”

Burian wrote the story from the perception he had at the time as a 13-year-old boy who had been living in a comfortable, loving Jewish home in what was then Czechoslovakia. Anhalt explained that one of his earliest memories of Nazi control was when he realized that his father, whom he thought was omnipotent, was helpless to confront the brutality. “He saw a guard search an influential Jewish woman in an inappropriate manner. He assumed his father would do something—but his father could do nothing. It was very jarring,” she said.

The family was taken to the ghetto and then to the Auschwitz concentration camp where Mengele immediately sent Burian’s mother, grandfather and great-uncle to their deaths. Burian’s father and brother were later sent to Dachau, leaving the 13-year-old alone. Burian said his father had told him three things that gave him the motivation to survive. “He said stay clean so you don’t get sick; stay a mensch, don’t let them make an animal out of you; and when everything is over, head home.”

Burian’s ability to understand and speak several languages saved him from death many times, and ultimately led to a reunion with his father and brother. At one point in Auschwitz, he heard one guard say to another, “Don’t bring the slop to this group, they won’t need it anymore.” He understood that the group would soon be sent to the gas chamber, and he managed to sneak out with the work detail.

After liberation, as a sick child, Burian tried to find his way home but needed to stop for help at a hospital in Budapest. Despite the fact that he was unable to pay, the hospital offered to house and care for him when they saw he could interpret for the doctors to explain the needs of the incoming Russian soldiers. One day he heard someone screaming for a doctor and ran out into the hall, falling over a man slumped by the door. The screamer was his brother; the man on the floor was his father. Later, when it became clear the family could not stay in Czechoslovakia, Burian’s brother settled in France and his father, who had remarried, followed Burian to America.

Burian’s memories are augmented by Yad Vashem’s rigorous fact checking and added details. “They will not take anything they can’t fact check. It took almost a year and they added footnotes of information I didn’t know as a child,” Burian said. Lawrence Burian said in a phone interview that Yad Vashem only accepts manuscripts from authors with the stamina to work with them through multiple reviews and edits. “Our family assumed publication costs but Yad Vashem will not put its imprint on a book if it is not accurate,” he said. “A Boy from Bustina” can be purchased through Amazon, and signed copies will be available at Ahavath Torah. All proceeds will benefit Yad Vashem.

By Bracha Schwartz