The gentile mob was massing outside the fortified villa walls and Avraham felt his fear mounting. Murmuring prayers and with his faith fortified, he prepared to confront the rioters outside. Avraham Pelengrino was alone in the Abensur home. He was there by choice; he could have opted to flee as virtually all of the Jews in the town did when the disturbances threatened to break out, but Abraham was made of tougher stuff—and perhaps he also had something to prove.

The year was 1617 and the location was the German port city of Danzig (also known by its Polish name as Gdansk).

Since the expulsion of the Jews from Spain and Portugal, many secret Jews, or Marranos, who had lived hidden lives as Jews while maintaining a Catholic facade, had slowly cultivated a vast network of commerce and trade spanning much of the European mainland, the Mediterranean, as well as many faraway colonies in the Americas and Africa.

One such family was the de Millao clan from Lisbon, Portugal. The Portuguese Jewish merchant Paulo de Millao (called Mosche Abensur in the Jewish community), son of the Marrano Enrique Dias Millao-Caceres from Lisbon, escaped from Portugal in 1610 and settled in Danzig. Other members of the family were found in the Portuguese “sister” community of Hamburg as well as in the “mother” community of Amsterdam of course.

As the historian Ronnie Perelis relates in his book “Narratives From the Sephardic Atlantic,” the aforementioned Moshe Abensur, formerly known as Paulo de Millao, set up a sugar operation in the Baltic port city of Danzig in 1613. Abensur came from a prominent family of Portugese-Jewish sugar merchants; his better-known brother-in-law, Alvaro Dinis, had set up a major import business in the port city of Hamburg.

The connection between our ger tzedek, Manoel Cardoso/Avraham Pelegrino, and the de Millao family begins in a Portuguese Inquisitorial dungeon in 1606. The aforementioned Enrique Dias Millao—the patriarch of the de Millao clan—was arrested by the Inquisition for active “judaizing.” He was eventually burned at the stake in 1609, deeply impressing his once cellmate, the young Manoel Cardoso. During their many talks in prison Abraham became convinced of the truth of the Jewish faith. He did not tell his inquisitors about it, but rather decided to fool them and pretend that he had recanted. He was released from prison and eventually escaped, along with members of the de Millao clan, to the freedom of Hamburg. There he underwent a formal conversion, was circumcised and took on the name of Abraham Pelengrino (which means “the wanderer”).

From a Comfortable Christian To an Indigent Jew

Pelengrino was born Manoel Cardoso de Macedo in Portugal in 1585. His family was a prominent “old Christian” one, as opposed to Marranos or Anusim.

Manoel started his life as the son of a wealthy businessman in the Portuguese Azores. He traveled to England to study because his father did business there. Manoel was a curious thinker and began growing uneasy and restless with the Catholic faith that he was inculcated with. England at the time was a Protestant country and that denomination of Christianity found appeal with the young Manoel. When he eventually returned to Lisbon, the Inquisition got wind of his new “heretical” beliefs and he was sent to prison where he met other prisoners, many of whom were secret Jews. One cellmate in particular made a deep impression on him—and that was the aforementioned Enrique de Millao, who would eventually be burned at the auto-da-fe for his beliefs.

Manoel recalled how the elderly Marrano handed him a book of Jewish law. He was shocked to find that there were still people in the world who actually kept the laws of the Bible. He spent an entire night reading the contents of that booklet.

He eventually made up his mind to leave Christianity behind completely and become a full-fledged Jew. He eventually escaped to the freedom of the bustling port city Hamburg to live his life as Abraham Pelengrino, the ger tzedek.

The twists and turns of Manoel’s fate are recorded in his own words. In his autobiography, he paints a picture that conveys the staunch religiosity of his strict family and the challenges that he was up against. In one conversation the father turns to young Manoel and says, “Son, have you said something against our Holy Faith? Because there is an inquisitorial official here to arrest you. If he would be here because you were a thief, a murderer or a highwayman I would save you, giving you my own horse and money, and if I would not have it I would carry you on my back, because this is what fathers do for sons, and sons for parents. However, for something pertaining to our faith, I would go myself seven leagues on foot to get the wood to burn you.”

The de Millaos in the Northern European Ports of Amsterdam, Hamburg and Danzig

The next leg of Abraham’s journey leads him to the children of his former cellmate—the de Millaos, who are still in Portugal. He is passionate about learning all he can about Judaism, noting wryly that in his father’s house it was always said that the Jews adore “the Toura” (a play on words, instead of Torah, “Toura” means a heifer). Manoel gains the confidence and trust of the de Millaos and is eventually entrusted with a plan to get the family out, but it goes awry.

Enrique’s widow entrusted him with a grand scheme that would take him as well as one of the de Millao daughters out of the country in the dead of night, but two officials at the Lisbon Customs House noticed the suspicious activity on the water and alerted the authorities. Amazingly, the inquisition does not suspect that Manoel is involved in Judaizing. Being of “old Christian” blood and recently arrested for flirting with Protestantism, the authorities are thrown off the scent of Judaizing on the part of Manoel.

He is able to manipulate his inquisitorial tormentors into thinking that there was no real plot, and they let him as well as his fellow arrestees go. In general, Manoel is treated differently by the Inquisition than he would have been had he been a Marrano or a “new Christian”; time and again the inquisitors appeal to his pure blood and urge him to drop his foolish acts and shape up.

Manoel wastes no time and plans an escape anew. This time he succeeds and lands at the de Millao estate in Hamburg. He does not stay there for very long and decides to travel on to another stake set down by a de Millao family member in nearby Danzig.

Enrique’s oldest son, Moshe Abensur, formerly known by his Christian name, Paulao de Millao, established a very lucrative sugar business in the port city of Danzig and he employed many servants. Moshe had a reputation as a very stern and strict man—a shrewd and enormously successful businessman with frenetic energy whose servants feared and respected him.

But one day, shortly after Rosh Hashanah, tragedy struck and all of it came to an end when one of Abensur’s “mulatto” servants turned up dead. The cause of the death was not ascertained, but it marked the beginning of the end for the family in that city. Immediately when word got out on the Danzig street, the local townspeople—filled with jealousy and hatred for the wealthy Jews—seized upon this development as yet another opportunity to lob the infamous blood libel charge. They immediately accused the local Portuguese Jews of having killed the gentile servant for Jewish ritual purposes. Filled with zeal and the prospect of filling their coffers with the Jews’ robbed goods, the locals streamed toward the Jewish quarter.

The small Poruguese-Jewish community in Danzig was seized with terror and Abensur made a hasty decision to leave his property behind and get out immediately with his family and close confidants. But Pelengrino—who had been retained by Moshe as a trusted employee on the estate—in a display of selfless loyalty or perhaps insane courage—made the decision to risk it all and stay behind to protect the Abensur’s property and goods.

As the bloodthirsty mob advanced upon the house, suddenly and mercifully, an even louder commotion was heard as several heavily armed constables pushed through the crowd and reached out to pluck the soon-to-be lynched Avraham from the crowd. From the frying pan into the fire—but still alive—Pelengrino is thrown into the city prison where his cellmates turn out to be violent, sadistic brutes. Pelengrino relates in his diary that he would rather take one month in the Inquisition dungeon than even one day in the Danzig penitentiary system. He eventually leaves prison a broken man in both body and spirit. He now walks with a limp and is also completely destitute.

Amsterdam: At Peace at Last

But Avraham was made of tougher stuff. He decides to make his way to the “mother” community of Amsterdam where the Jewish community warmly welcomes him in. By 1645 he was recorded as the shamash of the exquisite Portuguese Synagogue of Amsterdam. Interestingly, he is recorded as being put in charge of preventing non-Jews and so-called “Jewish-Christians” from entering the synagogue while services were in session. Not much is known of the “afterlife” of Pelengrino in his Amsterdam phase, although recently unearthed records seem to indicate that the community took him under their wing, ensuring that he was married off, thus leaving our tortured protagonist with a happy epilogue.

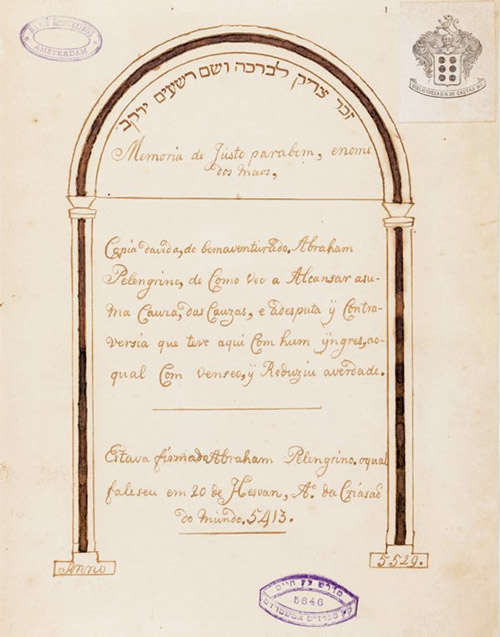

We know all this because Cardoso/Pelengrino wrote a spiritual autobiography while he was living openly as a converted Jew in Amsterdam. The text was titled “Vida do bemaventurado Abraham Pelengrino,” and it survives in a beautifully copied manuscript from 1769 in the collection of the famed Ets Haim Library in Amsterdam (see photo).

Source: “Narratives from the Sephardic Atlantic: Blood and Faith” by Ronnie Perelis. See here: https://iupress.org/9780253024015/narratives-from-the-sephardic-atlantic/

The author is the founding editor at Channeling Jewish History and can be reached at jhistorychannel@gmail.com.

By Joel Davidi Weisberger