The mishna on Bava Batra 64b discusses someone who sells his house without explicitly mentioning in the contract that he’s also selling the cistern on the land. In such circumstances, the pit/cistern isn’t included in the sale. However, how can the seller access that cistern, as he’d have to traverse the buyer’s property? Fourth-generation Tanna, Rabbi Akiva maintains that the seller must turn around and purchase an access path, while the Chachamim (Sages, presumably fourth-generation Tannaitic colleagues) say that this isn’t necessary, because an access path was surely also withheld from the sale.

In our slightly erroneous printed Gemara text (in Vilna, Venice and Pisaro), second-generation Rav Huna—who is Rav’s famous student who took over Sura academy after Rav’s death—quotes Rav that the we rule like the Sages1. Meanwhile, Rav Yirmeyah bar Abba I—a second-generation student-colleague of Rav—cites Shmuel that the halacha is like Rabbi Akiva. Rav Yirmeyah bar Abba I then challenges Rav Huna’s account of Rav; for he often said before Rav that we rule like Rabbi Akiva, and Rav never spoke up to oppose the idea.

Here we’ll interject to point out the irregularity. Yes, Rav Yirmeyah bar Abba will occasionally quote Shmuel, but he is really a primary student of Rav, and later teaches many of Rav’s students! Why should he put forth a Shmuel-oriented position, more than say, Rav Nachman or Rav Yehuda? Also, based on experience if not explicit words out of Rav’s mouth, he believes this is also Rav’s position, so he should say so up front—instead of only presenting it as Shmuel’s position. Neither problem is catastrophic, but it does seem slightly off.

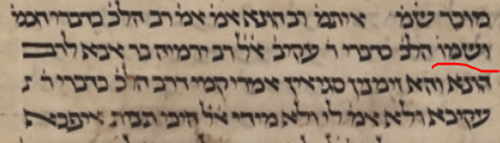

An examination of some manuscripts resolves these difficulties. One manuscript (Oxford 369) doesn’t have Rav Yirmeyah bar Abba present Shmuel’s position in the first debate, substituting Rav Nachman. While this makes more sense, it’s a likely mistaken copy from a bit later in the sugya, where Rav Nachman speaks. Instead, the likely correct text is as appears in Florence 8-9, Hamburg 165, Munich 95, Paris 1337, Escorial, Vatican 115b and the CUL: T-S AS 75.170 fragment in slight variation, namely איתמר רב הונא אמר רב הלכה כדברי חכמים ושמואל אמר הלכה כרבי עקיבא. We might interpret this as Rav Huna only citing Rav, and Shmuel’s statement as a standalone. However, as I’ve suggested works in dozens of other sugyot, this a double citation. Rav Huna first cites Rav, and then cites Shmuel. It is to this (in the aforementioned manuscripts) that Rav Yirmeyah bar Abba objects to his contemporary Rav Huna, that he thought Rav also holds the Shmuel position.

Aside from the satisfaction that comes from scholastic interactions making more sense, and in having the correct Talmudic text, there’s a possible pragmatic halachic ramification. As we’ll see in a bit, Rav Yirmeyah bar Abba’s version of the mishna reverses the Tanna and attributed position from what we have: (Rabbi Akiva, need purchase) and (Sages, implicitly withheld), so that Rabbi Akiva holds its implicitly withheld. If Rav Yirmeyah bar Abba were the one who tells us that Shmuel rules like Rabbi Akiva, Shmuel now rules the reverse of what we thought2!

Reversed Attributions

The sugya continues with Rav Yirmeyah bar Abba’s objection: “Many times I said before Rav that the halacha here was like Rabbi Akiva, and didn’t say a word to contradict it.” Rav Huna asked him, “How did you teach the mishna?” Rav Yirmeyah bar Abba explained how—which is the reverse Rabbi Akiva/Sages attribution than our text. Rav Huna explained, “That’s why he never said anything to you.”

There’s a parallel in Rosh Hashanah 22a. The Tanna Kamma in a mishna notes that relatives generally cannot combine together to form a pair of witnesses. Despite this, a father and son who witnessed the new moon should both come, so that if either is disqualified, the other can join with an unrelated witness. Rabbi Shimon maintains that, for new moon testimony, all relatives are valid to join together in a pair. Rabbi Yossi relates an incident in which Toviya the doctor, Toviya’s son and his freed slave all witnessed the new moon and went to testify. The Kohanim accepted him and his son as a pair, disqualifying the freed slave; the court, however, accepted him and the freed slave, disqualifying the son.

In the Gemara there, Rav Chanan bar Rava (second-generation Amora, Rav’s son-in-law and Rav Chisda’s father-in-law) said the halacha is like Rabbi Yossi. Rav Huna (again, Rav’s primary student) said the halacha is like Rabbi Shimon. Rav Huna’s argument is that this is Rabbi Yossi we are speaking of3! Also, there’s a practical incident! Rav Chanan bar Rava objected: “Many times I said before Rav that the halacha in this is like Rabbi Shimon, and he never said a word to me.” Rav Huna asked how he taught the mishna, and it was reversed from our version. Rav Huna said, “That’s why he never said anything to you.” Meanwhile, a different citation chain has Rav support Rabbi Shimon—presumably within the unreversed version of the mishna.

These two sugyot show a pattern in which Rav (a student of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi) doesn’t “correct” the attributions in a mishna to his own version, because the person reciting still maintains the correct applied ruling. Now, Chazal are not monolithic when it comes to attributions. You have some Amoraim like Mar Kashisha bar Rav Chisda—chastised by Rav Ashi for carelessness in attributions (Bava Kamma 96b). You have Amoraim like Rabbi Zeira—who are punctilious in citations—including quoting intermediate people in the citation chain (Yerushalmi Shabbat 6b). Several reasons exist for saying something in another’s name—sourced in different Gemaras—giving credit where it is due instead of plagiarizing; spiritual benefits; knowing the reliability of the tradition; building a Sage’s consistent legal theory and knowing how to rule.

There are rules of thumb for how to rule amongst Tannaim and amongst Amoraim, e.g., ruling like Shmuel in monetary matters as he was a dayan, or Rabbi Yossi over his colleague because his reason is with him. Attributions then conveniently often lead to an understanding of how to rule, without needing to explicitly state how we decide. Rav and Shmuel argue in this monetary matter? Just state the argument, and we know how to rule.

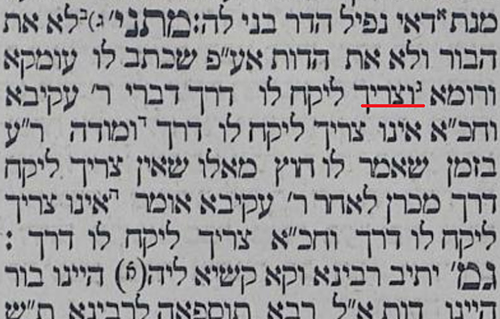

Consider the situation in the Vilna printing, which has footnote marks in different fonts, with and without brackets and parentheses. When I see the standalone block print gimel, I know I can look at the Ein Mishpat Ner Mitzvah in a top margin, and find where in Rambam, Tur and Shulchan Aruch it is discussed. Also, without even looking it up, since they place the footnote on the position with which we (or at least one of these sources) rule, that is the likely winner in a dispute. Thus—in the image shown—the Tanna Kamma wins.

This is convenient in a printed text. In a work transmitted orally—especially one which looks to be brief and thus easy to transmit / memorize—other approaches are appropriate. We often rule like the Tanna Kamma (assumed to be the non-individual position, or the anonymous voice of authorial authority) or the Sages (again, assumed to be plural). An Amora—more concerned with students understanding the accepted ruling than the precise attribution—could conceivably switch around the attributions, creating a source which lists the participants involved but also saying how we rule. This isn’t exactly what Rav does here. Rather, he believes the attributions truly go one way (with the Rabbanan, or Rabbi Yossi, winning), but doesn’t get into an argument regarding a variant—since it’s accompanied by a statement on how we rule.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.

1 Besides any compelling thought in the content of the position, or supporting evidence, we often rule like the Sages, who are assumed to be plural—thus a majority—over an individual Tanna. We also rule like Rabbi Akiva over his colleague—chaveiro, but it’s a matter of dispute whether we also rule like him over his plural colleagues—chaveirav.

2 Yet, immediately after in the sugya, Ravina and Rav Ashi assume that Rav and Shmuel disagree.

3 As we say in Eruvin 51b, רבי יוסי נימוקו עמו—“Rabbi Yossi’s reason is with him,” so we rule like him over his colleague.