There is a principle of זָכִין לְאָדָם שֶׁלֹּא בְּפָנָיו—Shimon can act on Reuven’s behalf to his benefit, even without Reuven’s explicit appointment to do so. However, אֵין חָבִין לָאָדָם שֶׁלֹּא בְּפָנָיו—we cannot act on Reuven’s behalf to his detriment. What if it’s to Reuven’s benefit (זָבִין) but to Levi’s detriment (חָבִין)? Does it matter if Reuven appointed Shimon as his agent?

Related to the above, Bava Metzia 10a discusses the following: Shimon lifts an item to acquire it, not for himself but for Reuven. That is, (A) הַמַּגְבִּיהַּ מְצִיאָה לַחֲבֵרוֹ. Does Reuven acquire? Rav Nachman bar Yaakov1 (third-generation Nehardean Amora) and his contemporary, Rav Chisda (Sura), both say לֹא קָנָה חֲבֵרוֹ, that it doesn’t work. Rabbi Yochanan (second-generation Amora, Teveria) says it works. The Gemara elaborates that this is based on (B), הַתּוֹפֵס לְבַעַל חוֹב בִּמְקוֹם שֶׁחָב לַאֲחֵרִים— “One who seizes for a creditor, to that creditor’s benefit, in a scenario where it’s to others’ detriment,” namely the other creditors. Rav Nachman/Rav Chisda maintain it doesn’t work; Rabbi Yochanan disagrees. (Rashi says it doesn’t work because he wasn’t explicitly appointed an agent; Tosafot disagrees.) Rava—Rav Nachman’s student—challenges him in two ways, but Rav Nachman successfully defends against the attacks.

A bit earlier, on 8a, Rami bar Chama tried to prove that “A” works from a careful analysis of the first mishna. However, Rava showed that it’s not a conclusive proof—perhaps since he’s acquiring part for himself, he can also acquire part for his friend, but generally not. Recall that Rami bar Chama is a fourth-generation Amora, who was Rav Chisda’s student and son-in-law. Fourth-generation Rava was also Rav Chisda’s student and son-in-law, marrying Rami’s widow. Still, Rava’s primary teacher was Rav Nachman. Interestingly, Rami deviates from Rav Chisda’s teaching, while Rava defends Rav Chisda’s and Rav Nachman’s position. Rav Chisda doesn’t speak up, nor is his position mentioned. Tosafot notes that Rava on 8a defends Rav Nachman’s position, so he must have accepted Rav Nachman’s rejoinders.

Consistency in ‘B’

Note that Rav Nachman and Rav Chisda don’t explicitly utter the words that “A is based on B.” Rather, the Talmudic narrator suggests this anonymously, perhaps because of global Talmudic knowledge or because the legal analysis is convincing. Rishonim might assume they explicitly said “B.” Regardless, the point of Talmudic attributions—aside from giving honor to those who developed the ideas—is to understand the consistent legal worldview of individual Tannaim and Amoraim. Can we propound two ideas simultaneously, or are they based on conflicting assumptions? If Ploni says Z, can the legal theory behind it be X?

In Ketubot 84b-85a, Yeimar bar Chashu was owed money by some debtor who died and left behind a boat. That debtor also owed money to fifth-generation Rav Pappa and Rav Huna bar Rav Yehoshua. Yeimar appointed an agent (as Tosafot stresses) to collect the boat. The two Sages intercepted the agent and said, “You’re trying to do ‘B,’” and Rabbi Yochanan says that doesn’t work. Rav Pappa steered the boat with an oar to acquire it entirely; Rav Huna bar Rav Yehoshua pulled it with a rope to acquire it entirely, and the case went forward from there.

Tosafot (our sugya, Ketubot and Gittin) point out the inconsistency in Rabbi Yochanan, for in Bava Metzia, Rav Chisda and Rav Nachman say, “A doesn’t work because A equals B and B doesn’t work,” and Rabbi Yochanan says, “A does work, so presumably, B should also work.” Tosafot answers that we need not equate A and B. Based on Rava’s distinction, since the lifter of the lost item could have acquired it himself, he can also acquire it for his friend, so “A” works. That doesn’t mean that “B” works.

We should also point out Rav Chisda in Gittin 11b. He says that “B” turns out to be a matter of dispute (בָּאנוּ לְמַחְלוֹקֶת) between Rabbi Eliezer (ben Hyrcanus) and the Sages in Peah 4:9. If someone acquires peah—the corner of the field left for the poor—on behalf of a particular pauper, Rabbi Eliezer says it works, while the Sages say it doesn’t work. The idea is that it benefits this pauper but paupers generally lose out. Much later, Amemar, or perhaps Rav Pappa—where both of them learned from Rava—suggests a Rava-aligned distinction: since he could abandon all his property, become a pauper and acquire for himself, he could also acquire for his friend. Assuming that Rav Chisda would rule like the majority of the Sages, this is a consistent Rav Chisda.

Consistency in ‘A’

In Beitza 39a, a mishna states about those who ascend from Bavel to the land of Israel, that water drawn from a public cistern has the travel boundary of the one who drew the water. What if one drew water and gave to his friend—מִילֵּא וְנָתַן לַחֲבֵירוֹ? Rav Nachman bar Yaakov says it’s the boundary of the recipient; Rav Sheshet says it’s of the drawer. The Talmudic narrator analyzes this. One Sage (Rav Sheshet) maintains the public cistern is ownerless; the other Sage (Rav Nachman) says it’s jointly-owned. Rava attacks him based on this understanding, and there’s a reply; either from Rav Nachman or likely the Talmudic narrator. However, this answer would be based on Rav Nachman maintaining that there’s retroactive specification/selection (בְּרֵירָה) in joint ownership, and the narrator quotes another sugya that shows he doesn’t. Rather, the narrator suggests, both Rav Sheshet and Rav Nachman maintain the public cistern is ownerless, but they argue in “A”—acquiring a lost (or equivalently, ownerless) item for his friend. Rav Nachman maintains that it works.

I’d have an issue with this, because the named Amora, “Rava,” should understand his teacher’s intent. Better to leave the objection with no resolution than to switch the underlying assumption and render Rava’s objection pointless. Especially if the Talmudic narrator is Savoraic or later, I’d take Rava’s word.

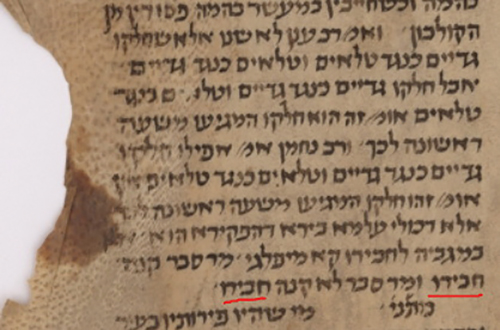

Rashi (there) and Tosafot (here and there) point out that this is a discrepancy. In Beitza, they attribute to Rav Nachman that A works—קָנָה חֲבֵרוֹ. In Bava Metzia, Rav Nachman explicitly says that “A” doesn’t work! Rashi answers that our texts shouldn’t read קָנָה חֲבֵרוֹ, but just קָנָה. It’s an extremely fine point, that the one who says לָא קָנָה intends that even the drawer doesn’t acquire for himself! Then, we can reverse Rav Nachman and Rav Sheshet such that Rav Nachman is consistent. The drawer intended something invalid, so he doesn’t acquire it, and it remains hefker (ownerless) until it reaches his friend’s hands. Our printed texts (Vilna, Soncino and Venice) and the Vatican 134 manuscript follow this emendation, but many manuscripts (Gottingen 3, British Library 400, Munich 95, Oxford 366 and Vatican 109) preserve the חֲבֵרוֹ.

Rashi’s emendation/interpretation seems forced, and I’d expect such a fine point that draws on the standard language of the “A” case, but in a counterintuitive way, to be more explicit. Tosafot finds the emendation far-fetched and notes other resolutions. Rashbam notes that for Rav Chisda and Rav Nachman, “A equals B, where B is that there’s a detriment to others.” Here, there’s no detriment, since there’s plenty of water to go around!

I’d consider Rashbam’s resolution forced as well—if the Talmudic narrator explicitly invokes a dispute about “A” and implicitly “B,” Rav Nachman’s position is reversed, shouldn’t it spell it out? The typical listener would assume that it’s the classic dispute about “A” as it applies in all cases. That’s what אֶלָּא הָכָא בְּמַגְבִּיהַּ מְצִיאָה לַחֲבֵירוֹ קָא מִיפַּלְגִי means—the classic Shas case—not the classic case with a carve-out, because of the particulars here.

Rabbeinu Tam wrote Sefer HaYashar to champion the old yet seemingly difficult girsaot against the onslaught of his contemporaries who sought to fix problems by changing the text. He defends קָנָה חֲבֵרוֹ, and reinterprets the Gemara with Rav Sheshet holding it works and Rav Nachman consistently holds it doesn’t. For Rav Sheshet, “A works, and that’s because of B;” “B works due to (Rava’s distinction of) ‘since he can acquire for himself, he can acquire for his friend.’” Since this is due to the drawer’s own abilities to acquire, it follows the drawer’s boundary. Rav Nachman disagrees. This also seems extremely complicated.

Perhaps simplest is Rabbeinu Chananel — who claims in Bava Metzia that Rav Nachman retracted from it not acquiring—based on Beitza where Rav Nachman maintains the opposite. Ramban is bothered by the Talmud omitting this retraction explicitly. I’d add: If the Talmud will mention an inconsistency in Rav Nachman about בְּרֵירָה, shouldn’t it discuss this inconsistency?

I wonder if the Talmudic narrator can be partially forgetful, recalling that there’s a dispute about “A,” maybe even that Rav Nachman weighed in, but forgetting that Rav Nachman actually held the reverse. Regardless, if this is a weakness in the Talmudic narrator’s position in Beitza, perhaps we can revert to Rava’s understanding and attack on Rav Nachman there.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.

1 Most texts have plain Rav Nachman, who is Rav Nachman bar Yaakov. Vatican 115 introduces him as Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak—Rava’s fifth-generation student—then continues with plain Rav Nachman, to refer to the “bar Yitzchak” mentioned earlier.