The Torah sometimes employs repetitive language, for instance הֹוכֵ֤חַ תֹּוכִ֨יחַ֙ (“You shall surely rebuke,”) and אִם־שָׁמ֨וֹעַ תִּשְׁמַ֜ע (“If you diligently hearken to Hashem’s voice,”). This doubled language seems unnecessary and calls out for midrash—hermeneutical interpretation. What about on a peshat level? We won’t diligently hearken to Ted Striker, that these divine commands were directed to Shirley. Rather, that’s just the way people speak, repeating words in alternate forms as flowery speech. Famously, דִּבְּרָה תּוֹרָה כִּלְשׁוֹן בְּנֵי אָדָם—“The Torah employs human speech patterns.”

Now, repetition is used in many languages for specific purposes. Latin poetry employs geminated vocatives (nouns used to address someone)1. For instance, in Ovid’s Metamorphoses 6:640: “Et ‘mater, mater’ clamantem et colla petentem—And ‘mother, mother’ crying out and pleading.” Compare “Moshe, Moshe,” which fifth-generation Rabbi Shimon (ben Yochai)—in the late Shemot Rabba 2:6—says is an expression of endearment and encouragement. Similarly, there are geminated imperatives (verbs instructing someone), in Plautus’ Curculio, “Retine, retine me, obsecro—Hold me, hold me, I beg you!”

If geminated vocatives/imperatives serve such purposes, maybe that’s what they mean in biblical verses as well, on a peshat level. Indeed, maybe that could also be called דִּבְּרָה תּוֹרָה, that human speech patterns are used for emphasis or exhortation, and, therefore, don’t stick out to warrant a midrashic interpretation. Consider that Babylonian Aramaic also includes doubled language. On Bava Metzia 3b, Rabba says אִשְׁתְּמוֹטֵי הוּא דְּקָא מִישְׁתְּמֵט מִינֵּיהּ, the denying borrowing is merely temporarily pushing off the creditor, and on Bava Metzia 6a—in explaining Rabbi Zeira—אִי דְּשָׁתֵיק, אוֹדוֹיֵי אוֹדִי לֵיהּ, the Talmudic narrator says that one of the pair grabs the entire tallit out of his fellow’s hand and the other is silent, he is effectively admitting that he doesn’t own it.

Comprehensive Coverage?

Despite the organic peshat explanation, Chazal will generally interpret stand-out elements of verses. Now, there are over 250 Biblical instances of duplicative language2. I don’t think that Chazal comprehensively explained every instance of duplication. Do they feel they must do so, that it is like a vow such that דָּרֹ֨שׁ יִדְרְשֶׁ֜נּוּ applies? If so, where there’s a gap in Tannaitic sources, maybe Amoraim can help fill the gap.

My sense is that Amoraim—unlike Tannaim—don’t generally directly interpret verses to present novel laws or determine the halacha. They might take the existing laws and discover the biblical source. The mishna on Bava Metzia 30b declared that even if a the scenario of a lost donkey or cow repeated itself four or five times, he must return it, because of Devarim 22:1, הָשֵׁב תְּשִׁיבֵם—“Return, you shall return3.”

On 31a, an unnamed Sage—הָהוּא מִדְּרַבָּנַן, says to Rava, הָשֵׁב חֲדָא זִמְנָא,תְּשִׁיבֵם תְּרֵי זִמְנֵי. This is understood as a bold question on the mishna’s derasha. Why don’t we restrict it to twice, rather than 100, meaning always? Rava response that actually, הָשֵׁב tells us even 100 times, while תְּשִׁיבֵם eases the burden of returning, not only to the owner’s house but even to his garden or ruin4. Is Rava arguing with the Tanna of the mishna, or is he saying that they are citing the context, but only intended the first word of הָשֵׁב תְּשִׁיבֵם?

Quantitative Versus Qualitative

I initially (mis?)understood this as the unnamed fourth-generation Pumbeditan Sage explaining, not attacking the mishna—with doubled language as a numerical derasha—with “twice” meaning repeatedly, even 100 times. Rava replies that this is the intrinsic nature of the biblical law, for each new occurrence is a new obligation described by the verse, and is captured by הָשֵׁב. Doubled language more generally should not be used for quantitative derashot, but qualitatively, to expand the nature of the act.

Rava did not pull this derasha out of his hat. On Bava Kamma 57a, third-generation Pumbeditan Amorim discuss it. Rabba argues with Rav Yosef, objecting via a baraita which makes this very deduction—הָשֵׁב—אֵין לִי אֶלָּא בְּבֵיתוֹ, לְגִינָּתוֹ וּלְחוּרְבָּתוֹ מִנַּיִן? תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר: תְּשִׁיבֵם מִכׇּל מָקוֹם. Besides answering the unnamed Sage, Rava is harmonizing two Tannaitic sources—known to Pumbeditans, predicated on the same5 doubled phrase. The general assumption is that each biblical phrase sources only one law, and each law is sourced in only one phrase. See Sanhedrin 34a, where Rabbi Yochanan, Abaye and Rabbi Yishmael may disagree about the former, but Rava’s not among them.

An unnamed Sage6 (perhaps the same one) continues telling Rava that in the doubled שַׁלַּח תְּשַׁלַּח, we send away the mother bird before taking the eggs/chicks once, and a second time. Rava responds that שַׁלַּח implies even 100 times and תְּשַׁלַּח is qualitative, that one must send it away even if he needs the mother for a mitzvah (such as purifying a leper7). We’ll note that again, the mishna in Chullin 141a seemingly interpreted the doubled language as even four or five times. Rava responds at least partly to the mishna, but wedges in an additional derasha. I don’t have another source for the qualitative derasha. Still, Rava’s nephew asks Rava’s student, Rav Kahana, why this additional derasha is necessary—since this law should follow from other principles.

An unnamed Sage tells Rava that in Vayikra 19:17, the doubled הוֹכֵ֤חַ תּוֹכִ֙יחַ֙ implies rebuking once and twice. We’ll note that in Arachin 16b, a baraita deduces from the doubled language that if he rebukes but isn’t heeded, he should rebuke again. Rava responds that הוֹכֵ֤חַ includes even 100 times, while תּוֹכִ֙יחַ֙ qualitatively implies even a student rebuking his teacher8. In Midrash Tanchuma Mishpatim 7, both derashot appear within different baraitot, so perhaps Rava’s not innovating.

The sugya continues with several other qualitative derashot of doubled language, where Rava doesn’t weigh in. Then, the next mishna (Bava Metzia 32a) interprets the duplicative עָזֹב תַּעֲזֹב to mean even if it recurs, four or five times. Earlier, עָזֹב תַּעֲזֹב was used to compensate for עִמּוֹ—to require unloading an animal collapsed under its weight even where the owner isn’t present, so we should consider how both are derived.

Quantitative Is Qualitative

Could quantitative derashot really be qualitative? That is, if someone doesn’t heed rebuke, might that indicate that they will take offense, or that they are someone who shouldn’t be rebuked? If someone’s ox is always running away, or always struggles under its burden, maybe there is something wrong with the ox, or with the owner’s attitude, so an obligation shouldn’t devolve on others, if not for doubled language. There are other derashot about עִמּוֹ, that he need act by himself if the owner opts out, unless the owner is old or infirm.

Consider the parallel Yerushalmi, Bava Metzia 2:10. A baraita (just as on Bavli 33a) deduces from רוֹבֵץ, that the animal is lying under its burden, and not that it is a רַבְצָן, one who habitually lies down. They contrast it to another baraita which says one should unload with him even 100 times in one day. They answer by distinguishing between habitual versus 100 times by accident. Similarly, they contrast כִּי תִּפְגַּע—encountering your enemy’s wandering ox—with the next verse, כִּי תִרְאֶה, if you see, which might imply even 100 mil away, compromising on 7.5 mil away. Here, 100 is distance, but also the trouble you need to go to. Quantitative might, thereby, be qualitative.

Finally, we could point to the doubled וְרַפֹּ֥א יְרַפֵּֽא, discussed in my earlier Jewish Link article, “Reshut for Doctors to Heal,” (January 25, 2024) on Bava Kamma 85a. There were three explanations of the doubling. Rav Pappa quoted Rava: to pay medical costs even when he pays for damage; a baraita discussed by Rabba (or alternatively Rava) conversing with the Sages of the (or Rav’s): if the wound reopens, he must again pay to heal him and pay shevet, his lost livelihood; Rabbi Yishmael’s academy: reshut (power or permission) is given to doctors to heal. The Talmudic narrator tries to fit in all three derashot, in a rather forced manner9. If Rava opposes the necessity of quantitative derashot, he needn’t derive repetitive healing. Conversely, there are qualitative aspects, such as payment of shevet, or whether a wound may be wrapped in a bandage, whereby the injured party caused the resurgence.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.

1 Examples drawn from “Repetition in Latin Poetry:” “Figures of Allusion” by Jeffery Willis.

2 Thanks to Daniel Rosen who sent me a spreadsheet categorizing these repetitions.

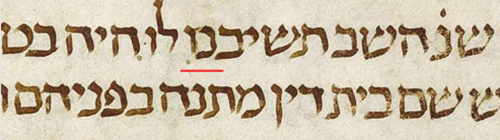

3 Some manuscripts like Munich 95 have the mishna cite Shemot 23:4, הָשֵׁ֥ב תְּשִׁיבֶ֖נּוּ לֽוֹ—encountering your enemy’s or donkey, which more closely matches the mishna’s animal list. Some manuscripts abbreviate the second word, leaving it ambiguous. Hamburg 165’s scribe wrote תשיבם, then erased part of the “mem sofit” changing it to a נו and followed it with לו. We can consider how it is discussed on Bava Metzia 31a and in the parallel Yerushalmi. In an alternate universe, this was this week’s article.

4 Indeed, the immediately following phrases discuss your fellow being distant or unknown to you—such that you store it in your own house, so location of return is what’s in scope.

5 But see footnote 1, whether it’s really the same doubled phrase and verse.

6 See manuscripts with הָהוּא מִדְּרַבָּנַן, unlike the printed text.

7 In addition to this qualitative expansion, note that Vayikra 14:7 discusses sending—וְשִׁלַּ֛ח אֶת־הַצִּפֹּ֥ר הַֽחַיָּ֖ה, so this sending preempts the other sending.

8 אֶת־אָחִ֖יךָ implies equal stature, so a qualitative derasha would include a power differential.

9 First אִם כֵּן, נִכְתּוֹב קְרָא וְרוֹפֵא יְרַפֵּא, and then more forced, אִם כֵּן, לֵימָא קְרָא אוֹ רַפֹּא רַפֹּא אוֹ יְרַפֵּא יְרַפֵּא, מַאי וְרַפֹּא יְרַפֵּא?