I’ve been thinking a lot about the shofar during this war and how its iconic, plaintive sound perfectly captures the emotional range of pain from the staccato shriek to the long and doleful howl that has characterized so many days since Oct. 7.

Maimonides describes the shofar as a wake-up call, an alarm that signals externally the work that must be done internally. That work varies in nature. In a famous Talmudic argument, the sages debate the use of a straight or curly shofar on the High Holidays (BT Rosh Hashana 26b). Should we use a straight shofar from an ibex to indicate our own rectitude on Rosh Hashanah when we are bent into submission and made crooked by our sins and save the straight shofar for Yom Kippur? Or, on Rosh Hashanah, should we use a coiled shofar because we are bent into submission as subjects to the King of Kings on God’s annual coronation? Then we stand erect on Yom Kippur with confidence that we will be forgiven and face the day tall and full of possibility.

Today, we only use one shofar on both holidays, a ram’s horn that is curved and twisted. I’ve always loved the shofar’s raw and primitive sound but until this year, I paid little attention to its shape. Its contours have simply been imprinted in my mind in the overfamiliar way that ritual objects look when we regard them as symbols. Although no two shofarot look the same, I never really registered how its gray-brown textured grooves or its varying lengths might affect my own spiritual longings and disappointments.

When it comes to the shofar, I carried only two mental pictures. There are the small, stubby ones you can pick up inexpensively as souvenirs in Jerusalem’s Old City and the fancy, curly ones, sometimes covered in places with a thin layer of sterling silver that sit in libraries and fancy offices. But I had no idea what the shofar we actually use in synagogue looks like because the person blowing it for the congregation has his head under a tallit and I usually keep my eyes closed to help me hear the shofar’s sound without distraction.

But the Talmud recognized that the shofar was more than a primitive musical instrument; it is also a symbol that both mirrors and directs our states of consciousness. Looking at its twisted shape validates our own minds and hearts when they are bent out of shape by the state of ourselves and the state of the world.

When we look at the shofar, we think of the freedom it introduced at the beginning of the Jubilee year. We stand at Mount Sinai when its sound echoed down the mountain and grew in intensity. Then we travel even further back in history and imagine Abraham coaxing the sound out of a ram’s horn after an angel stayed his hand on Mount Moriah and spared Isaac. “Abraham lifted his eyes and saw that behold, there was a ram, after this, which had been caught in the thicket by its horns. Abraham went, took the ram, and offered it up as a burnt offering in place of his son.” (Genesis 22:13)

In one midrash on this verse, a sage ponders the detail of a ram caught in a thicket by its horns. This detail seems unessential to the narrative. But two sages understood that it was a metaphor for Israel’s future entanglement in sin and misfortune. We get stuck and trapped in the thorns but the release of the ram and the use of its horn signals a way out of the thicket where danger lurks (Genesis Rabba 56:9). It reminds us that whatever peril is around us is less powerful than the strength within us. As the shofar’s note strengthens so too does our resolve.

One of my favorite shofar stories involves the writer and Nobel laureate S.Y. Agnon, who was one of the first residents of Talpiot. His house was, at the time of the War of Independence, close to the border with Jordan. There were not a lot of daily buses to the area and no telephones so residents used to go to the top of their houses and blow shofar to let them know when the bus arrived or when they needed to gather in the neighborhood. This detail of the early days of the state also appears in his story, “The Sign.”

The shofar made an appearance, of course, in the stories and Jewish texts Agnon collected for this season called “Days of Awe.” I only recently learned that he began work on it not long after Hitler came to power. He told his readers that he worked on the book during “troubled years

when our violent enemies stood up to destroy us.” At times he had to turn off the light and lie on the floor to avoid stray bullets. But he lived to complete the work, he wrote, despite dark times for the country.

“The shofar,” wrote Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, zt”l, reminds us “of our ultimate destination, telling us how far we’ve yet to go.” This year, I will not close my eyes as the shofar is blown. I will stare at the shofar, bent and warped, as a mirror of my own mind. This year, when I look at the curves in the shofar, I will see in it the twisted metal of thousands of cars and burnt houses. I will look at the way that the hate of antisemitism has distorted us and how violence has misshapen our belief in humanity. And I will think of the sage who argued that we should use a straight shofar to think of how we have stood.”

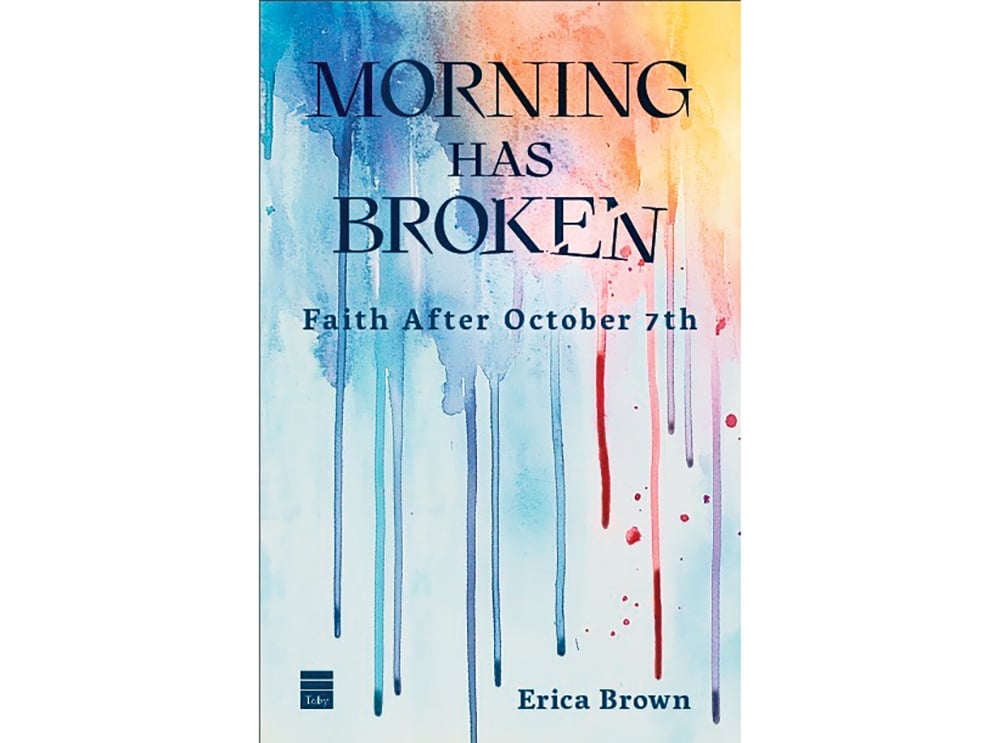

Dr. Erica Brown is the author of “Morning Has Broken: Faith After October 7th”(Toby Press/Koren). She serves as the vice provost for values and leadership at Yeshiva University and the director of its Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks-Herenstein Center for Values and Leadership.