Reviewing: “The Koren Tanakh of the Land of Israel—Exodus” Koren Publishers Jerusalem. 2020. 327 pages. ISBN-10: 965776033X.

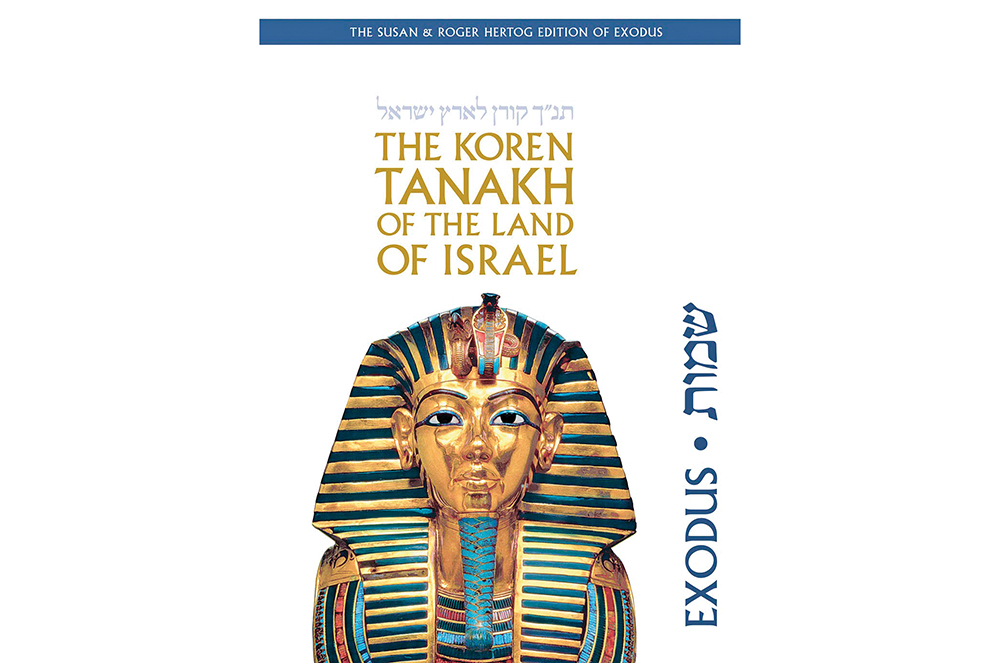

This beautifully produced volume features contributions from several scholars and is visually stunning. It includes high-quality graphics, maps and photographs of ancient inscriptions, artifacts and even medieval artwork. The typesetting is elegant, making it an attractive coffee-table book that draws in the reader. It includes color images, including reconstructions and archaeological finds, and maps illustrating the Israelites’ travels through the desert. However, this reviewer occasionally found it jarring to read sacred verses alongside images of idolatrous deities or partially unclothed figures.

While the book may be compared to Mossad HaRav Kook’s Da’at Mikra series, the key differences are that this volume is in English and places far less emphasis on traditional rabbinic commentary. It also does not provide a continuous commentary on the entire text of Exodus, focusing instead on select verses and themes. The articles consist of attributed contributions from many different scholars in a sort of “encyclopedic” format. Those articles are informative but tend to present basic, accessible information, and there are no footnotes or source citations, making it less suitable as a scholarly reference.

The layout is highly thoughtful: Icons are used to indicate the type of article (e.g., Egyptology, Language, and Near Eastern), and the visuals are in line with the book’s overall aesthetic sophistication. The “Egyptology” and “Near East” sections aim to contextualize the Torah by comparing or contrasting it with Egyptian and Mesopotamian culture and mythology. This highly comparative approach is one of the book’s most intriguing aspects. For example, the Egyptology entries often highlight how Biblical references to Egyptian culture subtly subvert those ideas to emphasize the supremacy of the God of Israel over nature and pagan gods. Most of the Egyptology entries were written by Dr. Racheli Shalomi-Hen of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. That said, not all entries labeled “Egyptology” are properly categorized. For instance, the etymology of the names Shifra and Puah (p. 8) is traced to Semitic/Hebrew roots, not Egyptian ones.

The “Flora and Fauna” sections were apparently penned by Dr. Zohar Amar from Bar Ilan University, a scholar whose work I have been following for some time now. But in this limited framework, those entries were obviously abbreviated and shorter than Dr. Amar’s more thorough work in his books on biblical and rabbinic flora/fauna.

The editors wisely steer clear of most chronological debates, probably due to the messiness of the topic. However, the volume does perpetuate several factual inaccuracies that have crept into popular consciousness. For example, it claims that Exodus 12:2 is the rabbinic source for the requirement that Nisan be in the spring (p. 63), whereas more accurate sources include Exodus 13:4, 23:15, 34:18 and Deuteronomy 16:1. The book also states (there) that the fixed Jewish calendar was established during the Second Temple period, even though rabbinic tradition attributes that development to Hillel II, who lived in the 4th century CE, well after the Temple’s destruction.

Furthermore, this volume states that tefillin are worn “on the forehead” (p. 72), an assertion belied by normative halakhic practice. On that same page, the book claims that tefillin were found at Qumran that correspond to both Rashi and Rabbeinu Tam’s opinions regarding the order of the texts in the tefillin, but that myth has already been dispelled close to 20 years ago in Dr. Yehudah Cohn’s 2007 article in Jewish Studies Quarterly. The book also asserts that the name of Pharaoh’s daughter who rescued Moses is unknowable from the biblical text (p. 12), neglecting to mention the midrashic identification of her as Bithiah based on I Chronicles 4:18.

Some of these oversights and others like them reflect a broader tendency in the book to favor archaeology, realia and cultural studies over traditional textual exegesis. The commentary on the Exodus narrative, in particular, leans heavily on Egyptology, sometimes at the expense of classic Jewish interpretations.

Each page includes the original Hebrew Masoretic text alongside a dignified English translation by Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, zt”l, accompanied by the thematic articles and visuals that are the centerpieces of this work. However, despite Koren’s generally impeccable reputation for Hebrew textual accuracy, this edition contains several proofreading errors. Extra letters that are not part of the Masoretic text appear in multiple locations—e.g., two extra yuds on page 13, an extra vav on page 32, an extra kaf on page 50 and another vav on page 62. Additionally, the colon that marks the end of a verse is sometimes laid over a letter instead of preceding it (for examples, see page 32, 61).

This review focused primarily on the first part of Exodus (chapters 1—17), which covers the narrative of the Israelites’ liberation from Egypt. The rest of the book should be treated separately, but in short, those later sections of Exodus primarily offer a legal code (roughly chapters 18—24) and a lengthy account of the Mishkan (“tabernacle”) with its associated appurtenances and paraphernalia (roughly chapters 25—40). In the legal sections, the articles mostly compare and contrast the Torah’s laws to the laws in other Near Eastern milieus. The Mishkan section is adorned with exquisite photographs that imagine how those components may have looked, with the scholarly articles mostly written by Rabbi Menachem Makeover and Professor Zohar Amar.

In terms of the book’s back matter, it contains an eclectic glossary that defines Jewish and Egyptian terms and situates them within their proper context for readers who might not otherwise be familiar with those ideas. It also contains a bibliography that offers sources and further supplementary reading to the book’s article (arranged by chapter and verse where the article appears), extensive photo credits and a helpful index.

In conclusion, The Koren Tanakh of the Land of Israel—Exodus succeeds as a visually-engaging and accessible introduction to the world of the Exodus story, especially for readers interested in its historical, archaeological and cultural background. Its stunning design and curated visuals make it ideal for casual reading or display, and its articles offer useful context for understanding the Torah’s setting and significance. However, those seeking in-depth engagement with traditional rabbinic commentary or rigorous academic sourcing may find its approach too limited. While the book brings much to the table, it would be best used alongside more traditional or scholarly works rather than as a standalone reference.

Rabbi Reuven Chaim Klein, an accomplished author and scholar, hails from Valley Village, CA, with extensive education and ordination from renowned figures. He’s known for notable books like “Lashon HaKodesh” and “God versus Gods.” Rabbi Klein is a prolific contributor to scholarly publications and offers expertise as an editor and subject-matter expert in Torah-related projects. He currently resides in Beitar Illit, Israel, open to research, writing, and speaking opportunities, reachable via email at rabbircklein@gmail.com.