By Rav Hershel Schachter

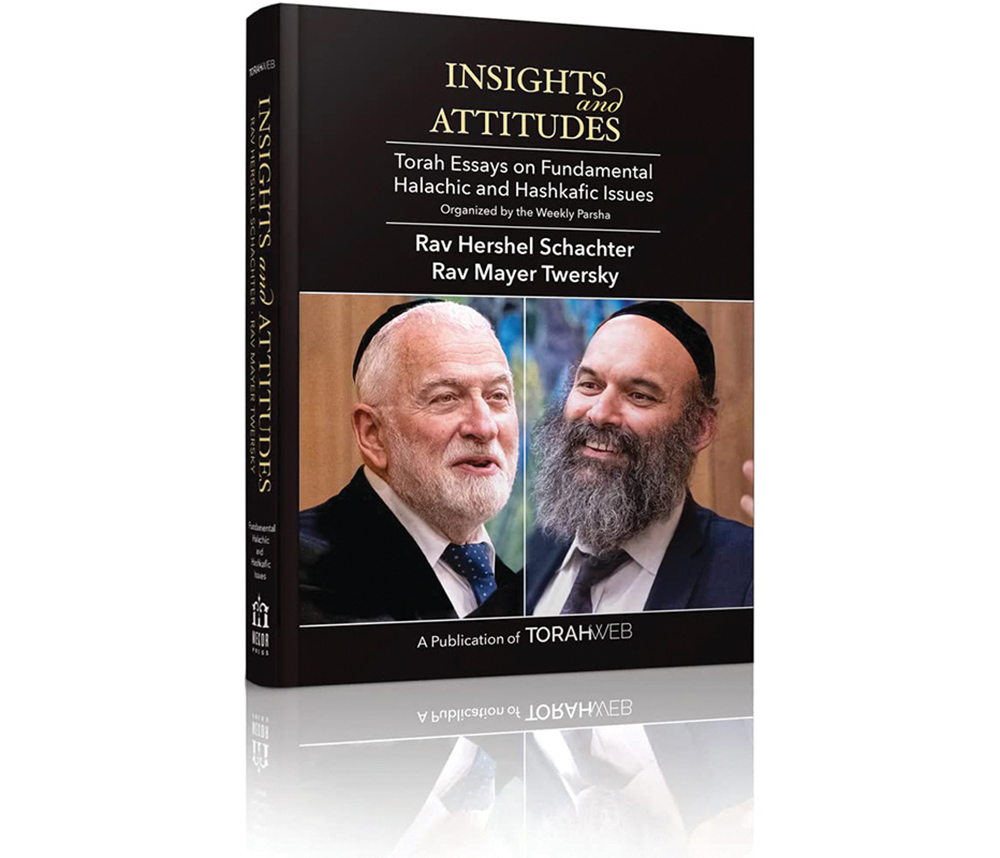

Editor’s note: This series is reprinted with permission from “Insights & Attitudes: Torah Essays on Fundamental Halachic and Hashkafic Issues,” a publication of TorahWeb.org. The book contains multiple articles, organized by parsha, by Rabbi Hershel Schachter and Rabbi Mayer Twersky.

I

Some of the non-Orthodox denominations celebrate the bas mitzvah of young girls at 13—the same age that the boys celebrate their bar mitzvah. These groups felt uncomfortable about the discrimination between the sexes which had been practiced by Jews for millennia, and finally did away with it.

The rationale for this distinction is presented by the Talmud as follows: the Torah says (Bereishis 2:22) that God created Eve from the body of Adam. The term used is “vayiven,” from the verb bana, “and He built.” The Rabbis had an oral tradition that this verb “vayiven” has an additional level of interpretation, from the root “bina.” “Bina yeseira, additional wisdom” was given to women more so than to men. Women mature intellectually at an earlier age than men; therefore girls should become bas mitzvah at age 12, while boys only attain their intellectual maturity at age 13 (Nidda 45b).

By insisting that the girls observe their bas mitzvah at age 13, just the same as the boys, one is in effect insulting women and denying that they were created with this bina yeseira.

In a recent study published in Time magazine (May 10, 2004, p. 59), it was reported that the brain mass of females reaches its maximum size at age 11, while that of the males only reaches its maximum size at age 12 and a half. It would appear that the ages of bar and bas mitzvah were established by the halacha in accordance with this attaining of maximum size of the brain mass, and the rabbis derived this point of biology from their additional level of interpretation of the pasuk in Bereishis. The Talmud (Bechoros 8b) relates that in the days of the Tanna’im, the Rabbis were able to read in between the lines of the Chumash and discover scientific details in the area of biology which the scholars of Athens had not yet ascertained through their scientific research. In later generations, however, this ability to darshen pesukim was lost, to the extent that the chachamim couldn’t even figure out halachos by reading in between the lines of the text of the Torah.

II

A new trend is emerging among certain “modern Orthodox” circles. A scholarly woman is called upon at a wedding ceremony to read the kesuba. They say that “halachically there is nothing wrong with this!” In a certain sense this statement is correct. If one only judges the issue from the perspective of the laws of siddur kiddushin, there’s nothing wrong. Strictly speaking, the reading of the kesuba is not at all a part of the marriage ceremony. This minhag was introduced in the days of the Rishonim, after the Geonim had done away with the ancient practice of having a long pause (of several months) between the erusin and the nissuin. When a young girl would marry for the first time, the pause would be “a yahr un a mitvoch.” The date for the chuppa would be set for the first Wednesday following the entire year after the erusin (see Kesubos 2a). In the days of the Talmud, there would have been no objection if בורא פרי הגפן were recited over the cup of wine used for the six berachos of nissuin, despite the fact that that same beracha had already been recited in connection with the cup of wine used for the birkas erusin,57 because there was a pause of months in between the two occasions. However, once the Geonim introduced the practice of having the nissuin follow immediately after the erusin, the reciting of the blessing of בורא פרי הגפן the second time seems very strange! There was no longer a pause of several months between the two berachos, but merely a pause of a few moments, and the reciting of the second beracha really seems absolutely unnecessary! This is what prompted the Rishonim to institute the slow reading of the kesuba in between the erusin and the nissuin, to establish a hefsek between the two berachos al hakos, so that the second בורא פרי הגפן will not seem so superfluous. It is for this reason that many have the practice that if someone is scheduled to speak under the chuppa, or if a chazzan is going to sing something, that these take place right after the reading of the kesuba. The greater the pause, the better. Some rabbis have the practice of reading the kesuba very quickly. I remember that when Rav Eliezer Silver, zt”l would be called upon to read the kesuba at a chasuna, he would do so very slowly. Since the whole purpose of kerias hekesuba is to introduce a pause between the berachos over the two cups of wine, the longer the pause, the better! (See BeIkvei HaTzon, p. 268.) So it is a correct observation that if one only studies Even HaEzer Hilchos Kiddushin and Hilchos Nissuin, there’s absolutely no mention whatsoever that anything is wrong with a woman reading the kesuba.

But when a shaila is researched one must look through the entire Shulchan Aruch, and consider all the various aspects of that shaila. Simply not appearing in Even HaEzer Hilchos Kiddushin or Hilchos Nissuin, does not make an issue non-halachic. Orach Chaim Hilchos Kerias HaTorah is just as halachic as Even HaEzer Hilchos Kiddushin. In Hilchos Kerias HaTorah, the Shulchan Aruch (282:3) quotes from the Talmud (Megilla 23a) that although judging from the perspective of Hilchos Kerias HaTorah alone a woman may receive an aliya, from the perspective of hilchos tzeniyus this is not permitted. All people were created betzelem Elokim, and the Torah has instructed each of us to preserve his tzelem Elokim. One aspect of Elokus is the fact that Hashem is a “Kel mistateir”; He always prefers to hide betzina. Therefore, we assume that part of our mitzva of preserving our tzelem Elokim is for all of us to lead private lives. The prophet Micha (6:8) uses the verb “leches” in conjunction with tzeniyus: והצנע לכת עם אלקיך. The Rabbis of the Talmud (Sukka 49b) understood the choice of that particular verb to be an allusion to the expression in Koheles (7:2)

טוב ללכת אל בית אבל מלכת אל בית משתה

This particular form of the verb appears in connection with a funeral and a wedding – occasions which are intended for a public outpouring of emotion. The navi Micha is telling us that even on these occasions, one should tone down the public display of his inner emotions. And kal vachomer—so much more so, all year long, one should try to lead as private (as tzanua) a life as possible.

Sometimes the halacha requires of us to act in a public fashion (befarhesiya), for example to have tefilla betzibbur, קריאת התורה בציבור, etc. On these occasions, the halacha distinguishes between men and women. We only require and demand of men that they compromise on their tzeniyus and observe certain mitzvos in a farhesiya (public) fashion. We do not require this of women. They may maintain their middas hahistaterus, just as Hashem (most of the time) is a Kel mistateir (Yeshaya 45:15). Of course, if there are no men in the shul who are able to lein and get the aliyos, we will have no choice but to call upon a woman, and require of her to compromise on her privacy and lein, to enable the minyan to fulfill their obligation of kerias haTorah. If there is a shul where a woman gets an aliya, this is an indication that there was no man who was able to lein, and this is an embarrassment to that minyan. This is what the Rabbis meant when they said that a woman should not lein—for this would constitute an embarrassment to the minyan (Megilla 23a).

The same is true regarding a woman reading the kesuba in public at a chasuna. Of course, the kiddushin will not be affected in the slightest! The truth of the matter is that no one has to read the kesuba! We have a centuries-old custom to create the hefsek through the reading of the kesuba. Because we plan to satisfy the view of the Rambam that the kesuba must be handed over to the kallah before the nissuin (see commentary of Maggid Mishna to Rambam, Hilchos Ishus 10:7), the Rishonim thought that we may as well read that kesuba which we’re just about to hand over. But nonetheless it is a violation of kevod hatzibbur to have a woman surrender her privacy to read the kesuba in public. Were there no men present who were able to read this Aramaic document?

III

Clearly the motivation to have a woman read the kesuba is to make the following statement: the Rabbis, or better yet—the God of the Jews, has been discriminating against women all these millennia, and has cheated them of their equal rights, and it’s high time that this injustice be straightened out!

What a silly misunderstanding! Our God never intended to cheat women of their rights and privileges! Quite the contrary! He wanted to give women the ability to fulfill vehalachta bidrachav in a more complete way—without ever having to compromise their tzeniyus.

IV

The Talmud records that during the period of the Second Temple the Tzedukim had many disputes with the Chachamim. The Tzedukim did not follow the Torah Shebe’al Peh, and had many complaints against the Rabbanim, based on their fundamental misunderstanding of the principles of the halacha.

One of their big issues was this issue of discrimination against women. According to the Torah law, a daughter will only inherit a parent when there were no sons. The Tzedukim felt that this was unfair, but there was nothing they could do about this because this point is explicit in the Chumash (Bamidbar 27:8). But the following case is not explicit: someone dies leaving a daughter, and they previously had a son who had predeceased the parent, and that son left a daughter, i.e., a granddaughter of the deceased. According to the halacha, the granddaughter receives the entire inheritance while the daughter gets nothing. The Tzedukim were famous for their dispute with the Chachamim in this instance, and they felt that the daughter should at least share along with the granddaughter (Bava Basra 115b). They preached that the Rabbis were cheating that daughter, and that women should have equal rights to those of men!

Years later, after the destruction of the Second Temple, the early Christians picked up some of the shtik of the Tzedukim. Just like the Tzedukim of old pushed Shavuos off to a Sunday, in order to have an extended holiday weekend (see Menachos 65a), so too the Christians pushed off the observance of Pentecost (the holiday of the 50th day) to Sunday. And so too they felt that the Rabbis had discriminated against women, so they preached (Shabbos 116b) that sons and daughters should always share an inheritance equally. They also did away with the women’s section in the synagogue and developed the notion that, “the family that prays together stays together.”

History repeats itself. In recent years, the Reform and the Conservative movements have expressed this same complaint against the rabbis, or better put—against the God of the Jews: discrimination against women! Look what has become of the Tzedukim, the early Christians, the Reform, and the Conservatives…

V

Rav Moshe Feinstein wrote in one of his teshuvos (Iggeros Moshe, Orach Chaim 4:49) that if a woman chooses to listen to shofar or to shake a lulav despite the fact that these are מצוות עשה שהזמן גרמא (time-bound positive mitzvos), we must determine what motivated her to do so. If she’s upset at the rabbis and at the halacha, and her shaking lulav and listening to shofar are done as a protest to the tradition, then these acts constitute an aveira. Only if her sincere desire to come closer to God is what motivates the woman to volunteer to do these mitzvos is she in the category of “אינה מצווה ועושה,” and deserving of reward.

VI

The non-Orthodox movements have whole-heartedly approved of women rabbis. We read in the papers that a certain “Orthodox rabbi” has stated publicly that “the stupidest thing about Orthodoxy is that they don’t approve of women rabbis.”

In Parashas Devarim we read that Moshe Rabbeinu appointed many rabbis to serve the community. The expression used by the Chumash (Devarim 1:13) is, “Let us appoint anashim.” Rashi quotes a fascinating comment from the Sifrei: what is the meaning of the term “anashim”? Was there even a “salka daitach” to appoint women rabbis?? The expression must certainly mean “anashim tzaddikim.”

Why was it so obvious to the Tanna’im that we cannot have women rabbis? After all, Tosafos (Bava Kamma 15a) raises the possibility of giving semicha to women, and having them serve on a beis din. So if women can possibly receive semicha, why can’t they serve the community as rabbis?

The answer is obvious. Although we must sometimes compromise on our midas hatzeniyus and do certain mitzvos befarhesiya (in public), this is not required of women. Women are not being discriminated against. They alone, unlike men, are given the opportunity to maintain their middas hahistaterus at all times.

VII

Our generation is so much into publicity that this midas hahistaterus is totally unappreciated. We live in a generation in which there is no sense of shame. People will do the most intimate and the most private acts in a most explicit and most demonstrative fashion. Their arrogant attitude has led them to believe that if they were God they would always be bragging, boasting, and showing off, always “making a statement.” They don’t have the slightest notion that God exists, is a “Kel mistateir,” and has created all of us with a tzelem Elokim, which also includes this middas hatzeniyus.

In some kehillos in Europe the nussach hatefilla for Birkas Rosh Chodesh included a request that God grant us “חיים שיש בהם בושה וכלימה”58 i.e., a sense of shame and a sense of tzniyus and privacy. We have a lot to pray for in our generation!

57 The truth of the matter is that historically, reciting of birkas erusin over a cup of wine seems to have been introduced during the period of the Geonim, and was probably not practiced at all in the days of the Talmud.

Rabbi Hershel Schachter joined the faculty of Yeshiva University’s Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary in 1967, at the age of 26, the youngest Rosh Yeshiva at RIETS. Since 1971, Rabbi Schachter has been Rosh Kollel in RIETS’ Marcos and Adina Katz Kollel (Institute for Advanced Research in Rabbinics) and also holds the institution’s Nathan and Vivian Fink Distinguished Professorial Chair in Talmud. In addition to his teaching duties, Rabbi Schachter lectures, writes, and serves as a world renowned decisor of Jewish Law.