Rachel Smilovitz isn’t the only one celebrating a milestone event this year.

2023 also marks the hundredth anniversary of the New York Yankees first home game in the Bronx, the opening of King Tut’s treasure-laden burial tomb in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings and the introduction of insulin to treat diabetes. But while those events are the stuff of history books, Mrs. Smilovitz, who turned 100 on March 12, is very much living in the present, her positive personality and ebullient smile winning the hearts of everyone she meets.

While today the centenarian uses a tablet to video call her children every night, Mrs. Smilovitz was born in a time and place when news was delivered by the town crier or on notices posted publicly in the center of Tachova, a middle class city located in the Carpathian region of Czechoslovakia. The daughter of Moshe and Shaindel Falikovic, the young Rachel grew up speaking Yiddish, Czechoslovakian and Hungarian as her home town shifted from one country to another in an evolving political climate that often had borders changing shape.

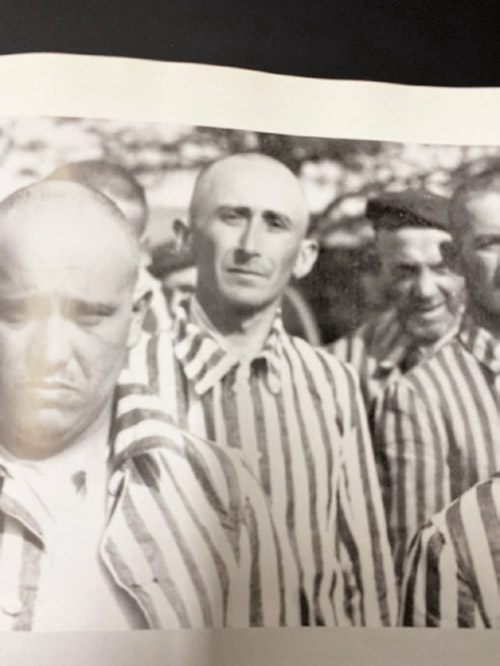

Like his brothers, Moshe Falikovic was a gifted sewer and the family tailor shop allowed him to provide for his family of nine, of which Rachel was the third to youngest. Even as the winds of war began blowing through Eastern Europe, life in Tachova remained relatively stable until the end of 1943, when three of Rachel’s brothers were among those who were sent to forced labor, while the city’s remaining Jewish residents were herded into a ghetto under the protection of the Hungarian government. Nazis photos bear testament to the ghetto’s liquidation in 1944, capturing haunting images of Tachova’s residents emerging from cattle cars after a horrific eight day journey to Auschwitz.

Rachel fared better than many others in the notorious concentration camp, her dexterity as a seamstress winning her a job threading bomb fuses in an ammunition factory, earning her access to slightly better food and clothing than the camp’s general populace. After liberation, Rachel spent time in a displaced person’s camp in Germany before being reunited in Tachova with three of her brothers, the only other surviving members of her family. Rachel also met up with childhood friend Nathan Smilovitz in Tachova, and the two married in Heidenheim, Germany, moving to Israel to start a new life together 1948 before relocating to Brooklyn 10 years later.

Like so many other Eastern European immigrants, the Smilovitzes didn’t have an easy time making a life for themselves on American shores, with both husband and wife joining the workforce to make ends meet. Despite the financial difficulties, the Smilovitzes refused to work on Shabbos and they made sending their children Chaya and Moishe to yeshiva a priority. Mrs. Smilovitz, who went to Erasmus High School to learn English and get an education, worked various part time jobs in a factory and in a cleaning store, providing her with an opportunity to contribute to the family’s financial needs while also being able to raise her children.

While Mrs. Smilovitz rarely discussed her wartime experiences, her Holocaust testimony was recorded by Steven Spielberg’s Shoah Foundation in 1996 and her picture has been displayed at the United States Holocaust Museum in Washington DC as part of the famous Auschwitz Album, which includes photographs of the Tachova transport arriving in the concentration camp. It was only after her husband’s death in 2011 that Mrs. Smilovitz began speaking openly about her life during the Holocaust, with various stories emerging over the years. One took place decades after the war, when Mrs. Smilovitz met a woman who thanked her for giving her sick sister her sweater on a bitter cold night in Auschwitz. The sister was taken to the infirmary the next day and never seen again, with the sweater that Mrs. Smilovitz had acquired just hours earlier in exchange for a prized ration of bread also disappearing. In another instance that also took place years after the Holocaust, Mrs. Smilovitz encountered a woman in Israel whose life she had saved in the final days of the war, carrying her for miles on her back during a death march.

In her later years, Mrs. Smilovitz also told her children how her mother had died after

Tachova’s Jews were herded into the ghetto and how she was unable to attend the funeral, but managed to save a small piece of her mother’s tachrichim – burial shroud. Her tailoring skills enabled Mrs. Smilowitz to sew a little pouch that she was able to keep with her in Auschwitz holding that tiny scrap of her mother’s tachrichim, something that she keeps with her until today.

With Mrs. Smilovitz finally comfortable sharing her personal history, son Moishe Smilovitz took advantage of an opportunity to ask his mother if she had any regrets in life. Without hesitating, Mrs. Smilowitz said that she always questioned why when she arrived in Auschwitz with her two sisters, one married with two children and the other single, she didn’t take the hand of one of the children as her younger sister had done.

“In the recesses of her mind, my mother wondered what prompted her sister to jump ahead of her and grab the child’s hand, an action that ultimately led to her being sent to the gas chamber, while her life was spared,” recalled Mr. Smilovitz, a former Teaneck resident. “I told her that God had a different plan for her and that we can’t question that, but to this day, it is still on her mind.”

Mrs. Smilovitz is believed to be the last survivor of the Tachova transport to Auschwitz, and currently lives in Boro Park in a building on 17th Avenue and 49th Street that was home to just a few Orthodox families when she first moved in. Today, the situation is vastly different and Mrs. Smilovitz is the bubby of the building.

“They treat her with such kavod,” observed Mr. Smilovitz. “There is so much warmth and chesed there that her neighbors are like an extended family to her.”

Mr. Smilovitz discovered just how much his mother enjoys her current living circumstances when she changed her mind about making aliyah with him and his family, deciding to stay in Boro Park instead.

“We had everything all set up but she decided at the eleventh hour that she was more comfortable in her own apartment and her own world and not deal with change,” explained Mr. Smilovitz. “We understood and at the end of the day, she has to make the decision on her own.”

Mrs. Smilovitz is, baruch Hashem, in good health and as recently as a year ago she was visiting the sick in hospitals and attending lectures and classes. She currently has a home health aide and many visitors who come to spend time with her, particularly on Friday nights when her neighbors, many of whom belong to different Chasidic communities, come to hear her share stories of a life well lived.

Despite the atrocities she endured, Mrs. Smilovitz has chosen to live a life of positivity.

“She always has a smile on her face regardless of how she feels and bears no grudges and has no regrets,” noted Mr. Smilovitz. “With all the deprivation she had in her life, you would think that my mother would have a sharp edge to her, but on the contrary, she only sees the good in people and is the most optimistic, uplifting individual in the world. We are truly fortunate to have her.”

Over 100 people turned out to celebrate Mrs. Smilovitz’s 100th birthday, with family members coming from as far away as Israel to mark the milestone event in Boro Park. Multiple children and grandchildren gave speeches warmly sharing their favorite Bubbie stories with the many cousins and friends in attendance, which also included Mrs. Smilovitz’s social worker and long time physician.

“My mother spoke too, about how grateful and gratified she was to see all the family assembled from all over the US and abroad and to see the nachas of how educated, religious and successful they all are, but most importantly that they are good upstanding people,” said Mr. Smilovitz.

Smiling broadly throughout the party, Mrs. Smilovitz posed for pictures with her nachas, the opportunity to enjoy her birthday with the people she loves most, the greatest gift of all. Wheeling his mother back to her apartment after the party carrying a large bouquet of balloons bearing the number 100, Mr. Smilovitz said that numerous people stopped to wish her good health ad meah v’esrim – till 120.

“Cars stopped to take a picture of this beautiful beaming person in a wheelchair and to wish her well even backing up traffic to do so,” recalled Mr. Smilovitz. “It was an amazing acknowledgement and an amazing scene. She was walking on air!”

By Sandy Eller