Part XIV

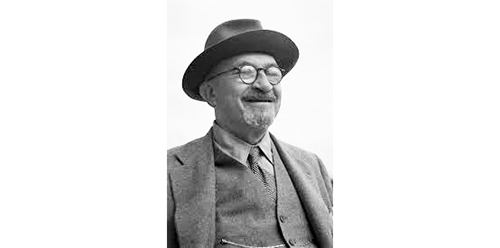

For Chaim Weizmann, president of the English Zionist Federation, the Balfour Declaration “represented a tremendous event in exilic Jewish history, [ushering in] “a new chapter … full of new difficulties, but not without its great moments.”

The suggestion that the Balfour Declaration was a reward for Weizmann’s contribution to Britain’s war effort was debunked by Herbert Samuel, the first high commissioner for Palestine. Weizmann developed a new bacterial process to manufacture acetone, an essential ingredient in the production of cordite, a smokeless propellent used in small arms, which was in perilously short supply during WWI. By March 1916, Weizmann’s procedure eased the problem, Samuel noted.

Samuel adds: “It is dramatic, but incorrect and unfortunate to represent so great an event as the Balfour Declaration … as though it were partly a douceur given, instead of a knighthood or a decoration….” Without despairing his service, “if acetone had never been heard of, I believe that the Balfour Declaration would have taken precisely the shape it did, and been promulgated just when it was.”

Weizmann’s Role in Perspective

Samuel acknowledged that Weizmann’s “tenacity, resourcefulness, and remarkable powers of persuasion have often been put to the test, usually with remarkable success. The astonishing achievements of Zionism over a period of thirty years have been made possible largely by his leadership.”

“Without Chaim Weizmann, there would have been no Jewish state,” asserts historian Jehuda Reinharz, author of several books on Weizmann. He concludes, “He’s one of the rare incidents in history where an individual without power, without land, without a language, without people behind him, without even the Zionist organization fully behind him is able to persuade leaders, first of all, Great Britain to issue a letter, a letter that eventually became known as the Balfour Declaration.”

He was “a man possessed, behind the scenes, with one purpose: to persuade the British government to issue to the Jewish people the promise of a Jewish state in Palestine,” opines historian Martin Kramer.

He quotes Isaiah Berlin, the British philosopher and political theorist, who reflected on how Weizmann had “this extraordinary capacity for creating the illusion that there existed a fully formed nationality whose true elected representative he was, that there was not only a nation but very nearly a state … (when everyone knew that this was not the case). … By behaving as he did, he cast a spell upon foreign statesmen and assimilated Jews alike.”

Though Weizman played a pivotal role in the creation of the State of Israel, Kramer points out there were three decisive events, without which there would not have been a Jewish state: the First Zionist Congress at Basel in 1897; the Balfour Declaration in 1917; and Israel’s Declaration of Independence in 1948.

Each event, he said, depended on the persistence and resolve of one leader: Theodor Herzl for the Zionist Congress; Chaim Weizmann for the Balfour Declaration; and David Ben-Gurion for the Declaration of Independence.

It is also important not to forget that Herzl, Weizmann and Ben-Gurion “shined only for an hour,” he observes. “They weren’t endowed with infallible judgment, they all made mistakes, they all had cogent critics, and they all finished very much on a low note.”

Other individuals who played significant roles were Aaron Aaronsohn, Chaim Arlosorov and Ze’ev (Vladimir) Jabotinsky.

Aaronsohn, a world-renowned scientist, led NILI—Netzach Yisrael Lo Y’shaker (the Champion of Israel will not deceive [Samuel 1 15:29])—a pro-British spy ring providing critical intelligence about the state of the Turkish military and the internal conditions in the region.

Douglas J. Feith, a former U.S. undersecretary of defense for policy, notes that when William Ormsby-Gore, a British liaison officer and a future colonial secretary, informed the British Foreign Office that NILI was “admittedly the most valuable nucleus of our intelligence in Palestine during the war,” he added, “In my opinion, nothing we can do for the Aaronsohn family will repay the work they have done and what they have suffered for us.”

Chaim Arlosorov, a young labor leader, was one of the organizers of the Histadrut (The New General Workers’ Federation), and represented the Yishuv (the Jewish community of Palestine) at the League of Nations in Geneva.

As head of the political department of the Jewish Agency, he and other political and economic activists were instrumental in negotiating the Haavara Agreement with Nazi Germany in August 1933. This allowed approximately 20,000 German Jews with capital to flee Nazi Germany to Palestine with their financial assets—about 37% of all German Jews, according to historian Yehuda Bauer.

Ze’ev Jabotinsky, who founded the Zionist Revisionist movement, was involved in the creation of the Jewish Legion in the British Army. He enlisted as a private that was attached to the 20th Battalion of the London Regiment and fought as a combatant.

As a strong advocate for the historical right of the Jewish people to return to their ancestral home, as early as 1919 he urged them to come home in large numbers. With regard to Arab hostility to Jewish immigration, he understood the futility of trying to convince the Arabs that their lives would be better because of the Jewish presence in Palestine. He publicly warned of the folly of trying to entice the Arabs with economic riches.

Dr. Alex Grobman, a Hebrew University-trained historian, is senior resident scholar at the John C. Danforth Society and a member of the Council of Scholars for Peace in the Middle East.