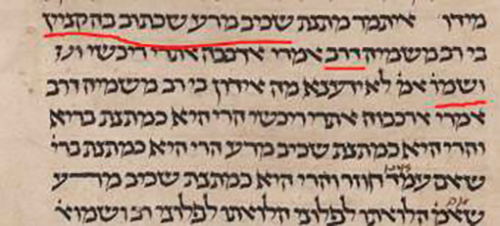

My focus in this column will be about that famous Amora, Rabbi Mana, who was the brother of second-generation Rav Huna, and how this relates to our sugya in Bava Batra 152b. Rabbi Mana says מַתְּנַת שְׁכִיב מְרַע שֶׁכָּתוּב בָּהּ קִנְיָן, אִם עָמַד אֵינוֹ חוֹזֵר. This indicates that when a dying person formalizes their gift with a kinyan, it becomes irrevocable, even if they later recover.

To expand on this a bit, Rav Huna’s brother, Rabbi Mana, is mentioned in the context of a legal discussion concerning property and inheritance. The passage deals with the issue of a father gifting property to one of his sons before his death, potentially to the exclusion of his other heirs. This situation could raise concerns about fairness and legal validity.

Rabbi Mana plays a significant role in clarifying the halakhic implications of such transactions. Specifically, the Talmud examines whether such gifts are binding if made in a certain manner, such as when the father is on his deathbed (a מַתְּנַת שְׁכִיב מְרַע). The passage grapples with questions about whether these gifts are considered irrevocable or conditional and whether they may contravene the principles of equitable distribution among heirs.

Rabbi Mana’s involvement reflects the broader scholarly discourse on property laws, emphasizing the balance between the rights of the individual to allocate their property and the expectations of the heirs under Jewish law. This discussion highlights the meticulous care the Talmud takes in addressing interpersonal and familial relationships through the lens of legal structures.

A Second-Generation Amora

The Meiri contextualizes Rabbi Mana as a figure from the second generation of Amoraim and highlights how this background influenced his legal interpretations.

Rabbi Mana’s connection to earlier generations of Amoraim, including the traditions passed down by Rav and Shmuel, shaped his perspective on the principles governing מַתְּנַת שְׁכִיב מְרַע. The Meiri points out that Rabbi Mana adhered to the stricter formulations of these laws, emphasizing the conditional nature of such gifts. This was partly because second-generation Amoraim were more directly influenced by the Tannaitic traditions that framed the legal framework for such cases.

Specifically, Rabbi Mana viewed a מַתְּנַת שְׁכִיב מְרַע as fundamentally provisional. The gift was intended to take effect only if the giver passed away from their illness, reflecting the mindset that these gifts are not final but rather contingent on the giver’s death. If the giver recovered, the gift was automatically nullified.

The Meiri also underscores Rabbi Mana’s broader concern for protecting the rights of heirs and ensuring that the distribution of property adhered to the principles of fairness and equity rooted in halakha. By grounding his rulings in earlier traditions, Rabbi Mana sought to maintain a balance between the autonomy of the dying individual and the collective interests of the family.

This perspective highlights how second-generation Amoraim like Rabbi Mana played a critical role in bridging the Tannaitic legal traditions with the evolving needs of their communities. The Meiri’s analysis of Rabbi Mana reflects the broader trends of halakhic development during the early Amoraic period.

Variant Texts

A slight problem arises when we examine “Hachi Garsinan,” which provides alternative girsaot. Rabbi Mana’s statement does not appear in Munich 95, Vatican 115b, Hamburg 165, or any other manuscript. In fact, it doesn’t appear in any printing, including the Vilna Shas! How could Meiri have written this then?

The answer is that Meiri didn’t write this, nor did Rabbi Mana say this, nor did Rav Huna have a brother named Rabbi Mana. The first half of this column was written mostly by ChatGPT,1 which will often “hallucinate,” or make things up. And it made something up convincingly— it tied Rabbi Mana’s idea to Rav and Shmuel, who did stake out positions on the daf. You cannot trust what ChatGPT says, even though it presents it in a confident and erudite manner. It is easy for people to not realize this, because a lot of what ChatGPT will produce is in fact correct, or will be outside people’s direct experience. Therefore, they won’t realize when it produces nonsense.

The Gell-Mann Amnesia Effect

This tangentially relates to an effect described by Michael Chrichton: “Briefly stated, the Gell-Mann Amnesia effect is as follows. You open the newspaper to an article on some subject you know well. In Murray [Gell-Mann]’s case, physics. In mine, show business. You read the article and see the journalist has absolutely no understanding of either the facts or the issues. Often, the article is so wrong it actually presents the story backward — reversing cause and effect. I call these the «wet streets cause rain» stories. Paper’s full of them.

In any case, you read with exasperation or amusement the multiple errors in a story, and then turn the page to national or international affairs, and read as if the rest of the newspaper was somehow more accurate about Palestine than the baloney you just read. You turn the page, and forget what you know. That is the Gell-Mann Amnesia effect. I’d point out it does not operate in other arenas of life. In ordinary life, if somebody consistently exaggerates or lies to you, you soon discount everything they say. In court, there is the legal doctrine of falsus in uno, falsus in omnibus, which means untruthful in one part, untruthful in all. But when it comes to the media, we believe against evidence that it is probably worth our time to read other parts of the paper, when, in fact, it almost certainly isn’t. The only possible explanation for our behavior is amnesia.”

Speaking for myself, the area of knowledge is Talmud, Talmudic biography, and computer science. For readers of this column, it might be something else. Often, when we consult an LLM, it is for something we don’t really know about, so will be unable to spot mistakes. My hope is that the amnesia effect does not kick in, and that seeing it can confidently generate erudite nonsense in one area will cause us to pause for a moment, as we increasingly interact with these AIs.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.

1 See my chat here: https://chatgpt.com/share/673a05dc-4b54-8011-a741-cf68231aa1f7