In Bava Kamma 66, we listen in on a debate in Pumbedita academy which spans two or three scholastic generations. There are ambiguities whether certain statements were said by Rabba or Rava, or Rava or Rav Pappa, and resolving them can help us apply decisive principles or establish consistent Amoraic positions.

The order of statements are: א) אָמַר רַבָּה… ב) וְרַב יוֹסֵף אָמַר … ג) אֵיתִיבֵיהּ רַב יוֹסֵף לְרַבָּה… ד) אֲמַר לֵיהּ… ה) אֵיתִיבֵיהּ אַבָּיֵי לְרַבָּה… ו) אֲמַר לֵיהּ רָבָא… ז) אֵיתִיבֵיהּ אַבָּיֵי לְרַב יוֹסֵף… ח) אֲמַר לֵיהּ… ט) מַתְקֵיף לַהּ רַבָּה בַּר רַב חָנָן… י) אֶלָּא אָמַר רָבָא… יא) רַבִּי זֵירָא אָמַר…

In (א), Rabba (bar Nachmani), a third-generation Amora, said that if a thief modifies the object he stole, he thereby acquires it, and sourced this to both Biblical verse and a Mishnah, so that its a Biblical rule. However, regarding the owner giving up hope – יֵאוּשׁ – it is unclear if the thief acquires it Biblically or only Rabbinically. In (ב) Rav Yosef (bar Chiya), a third-generation Amora, says that the thief doesn’t even acquire it Rabbinically.

These Sages were contemporaries. Rabba led Pumbedita for twenty-two years until his death, then Rav Yosef for two subsequent years (Berachot 64a, referenced in our sugya). Amoraim appear chronologically, with Rabba always before Rav Yosef. Fourth-generation Rava led Pumbedita later, and would have appeared later. It’s clearly Rabba in (א).

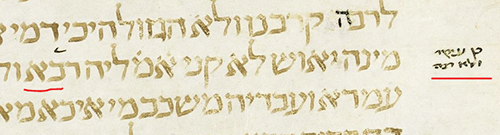

In (ג), Rav Yosef objects to Rabba, his disputant. In (ד), no new person is introduced, and כִּי קָאָמֵינָא אֲנָא, “that which I said”, implies the same speaker Rabba1. In (ה), fourth-generation Abaye analyzes a brayta – ״קׇרְבָּנוֹ״ – וְלֹא הַגָּזוּל – and objects to his teacher / uncle Rabba, who said יֵאוּשׁ works. This אֵיתִיבֵיהּ אַבָּיֵי לְרַבָּה parallels the later ז, where Abaye addresses his other primary teacher and Rabba’s disputant, Rav Yosef. We mention the target, רַבָּה, to highlight the position being attacked.

In (ו), Rava responds to Abaye. Here’s the ambiguity. Should this still be Rabba, or should we transition to Abaye’s fourth-generation contemporary? In (ז), Abaye attacks Rav Yosef. In (ח), Rav Yosef responds though, as in ד, no names are explicitly mentioned. In (ט), Rava bar Rav Chanan, Abaye’s a fourth-generation Pumbeditan contemporary2, attacks Rav Yosef’s answer. In (י), Rava – here it’s clearly Rava – says that for 22 years, this matter (an object’s name change) was a difficulty posed by Rabba to Rav Yosef, until Rav Yosef sat at the head and resolved it as follows… In (יא), Rabbi Zeira II, a fourth-generation Pumbeditan Amora, offers another answer. The Talmudic Narrator then continues the analysis.

After an interlude, on 66b-67a, Ulla derives from a verse in Malachi that יֵאוּשׁ doesn’t allow the thief to acquire, and Rava derives by analyzing a brayta citing a verse in Vayikra. ״קׇרְבָּנוֹ״ – וְלֹא .הַגָּזוּל The analysis: if it were sanctified by the thief before despair, it’s too obvious. Thus, the brayta is speaking of after despair, yet it doesn’t work.

The problem, the Talmudic Narrator notes, is that this analysis of the brayta is identical to Abaye’s objection to Rabba in (ג). And to this, in (ד), Rava refuted Abaye, using an analogous brayta to demonstrate how this brayta need not discuss a stolen animal sanctified after despair, but rather could be that he stole a sacrifice already sanctified by his friend. If so, how could the same Rava bring this brayta and analysis thereof to prove Rav Yosef’s position? The Talmudic Narrator suggests that either Rava retracted, or one of these two statements was really Rav Pappa.

Rabba or Rava?

A common scribal error is confusing רבה with רבא, and on Bava Kamma 67b, where Ulla and then Rava offer derivations, Tosafot d.h. רבא אמר declares that that text should read Rava, not Rabba. Their proof is that the Talmudic Narrator suggested that there was a Rava / Rav Pappa confusion. Rava is Rav Pappa’s primary teacher, making the confusion possible. After all, Rav Pappa may have stated his own words without ascribing them, the audience might have thought it was from Rava. No such possible confusion exists between Rabba and Rav Pappa. Once we select Rava here, we must also change Rava earlier on 66b in (ו), where the drasha was originally made.

Tosafot continue that even though Rabba is Rav Yosef’s (current and regular) disputant (in א and ג), and Abaye objected to Rabba in (ה), we’re compelled to say that Rabba didn’t himself respond in (ו), but rather Rava responded on his behalf. Indeed, all manuscripts before Tosafot have Rava there. Further, if Rabba himself had responded, it could have just said אֲמַר לֵיהּ. I’d add that we don’t explicitly write that it was Rav Yosef who replied in (ד), since it’s obvious. Having established Rava’s position (or potentially so, since maybe Rav Pappa said it) that despair alone doesn’t acquire, Tosafot proceed to examine other sugyot across the Talmud where particularly Rava’s position is relevant.

Manuscript Evidence

Now, some manuscripts differ as to where Rabba and Rava appear. Vatican 116 has Rava throughout, even where it makes little sense – I suspect this was an overcorrection due to Tosafot. Escorial similarly makes numerous changes or blurrings between Rabba and Rava, again likely due to uncertainty. However, the Florence 7-8, Munich 95, and Hamburg 165 manuscripts, and the Vilna and Venice printings, all transition from Rabba to Rava at (ו) and stay there. They’re also likely influenced by Tosafot’s commentary. Indeed, Hamburg 165 has a marginal note הכי גרס התוספות by Rava’s prooftext following Ulla, and has Rava in (ו) with a marginal note כן עיקר ולא רבה. Though recall that Tosafot already said that manuscripts they saw had רבא.

Tosafot assumed that this Rava / Rav Pappa confusion was due to listeners mistaking Rav Pappa’s own words to be that of his teacher. I’m reminded of Rabbi Dr. Yaakov Elman, Orality Orality and the Redaction of Babylonian Talmud, arguing for an oral provenance for אִיתֵּימָא, writing “the variant attributions can often be understood as possibilities arising from the vagaries of association, where the Amoraic statement is attributed to contemporaries who are closely associated, as in the case of R. Yohanan and his close disciple, R. Abbahu (Pes 100a).” In “That’s What They Say” in the Jewish Link, April 28, 2022, I argued upon that particular example, but I understood Elman to suggest a mental slip. A mental slip / association would also recommend Rava over Rabba.

I argued in that article for orthographic confusion, stemming from similarity between ירמ starting Yirmiyah and יוח starting Yochanan. I can’t explain Rava / Rav Pappa in this particular sugya in this way. However, I regularly learn Daf Yomi with Hachi Garsinan variants pulled up on my smartphone, and a Rav Pappa / Rava switch is fairly common. Sometimes I can explain it via hasagat gevul – that there are Rava statements followed by Rav Pappa statements, and scribes were confused as to the boundary line where Rav Pappa began. Other times, I can explain it as an orthographic error. רבא sometimes is abbreviated to רב with a diacritic over the bet. Also, רבא begins with רב and ends with א, and so does רב פפא. Sometimes words are abbreviated at ends of lines,with just the initial letters on one line and then repeated on the next line. Also, sometimes the word after the Rava / Rav Pappa confusion begins with a פ.

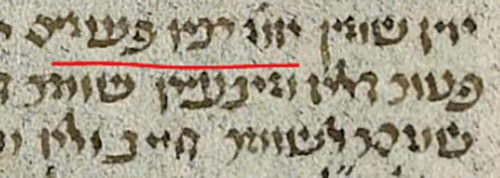

One such example is Bava Kamma 11b, which has Ulla cite Rabbi Eleazar, then Rav Pappa commenting, with words beginning with a peh: …אָמַר רַב פָּפָּא: פְּעָמִים. Florence 8-9 matches printed text with “Rav Pappa”, but Hamburg 165, Munich 95, and Vatican 116 have “Rava”. Further, a bit higher, Ulla cited Rabbi Eleazar and Rav Pappi commented, and a bit lower, Ulla cited Rabbi Eleazar and Rava commented, according to all manuscripts. It’s both the פ influence and hasagat gevul. Thus, other forces can cause a Rava / Rav Pappa exchange, or perhaps even a Rabba / Rav Pappa exchange.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.

1 Hamburg 165 omits אֲמַר לֵיהּ and Vatican 116 turns it to אלא, but these are errors. Rav Steinsaltz, in his interpolated commentary writes “Rabba”, but the English Koren translation erroneously wrote “Rava”.

2 and the person really in the famous story of youths saying where Hashem dwelt, so that they could join in mezuman