Not all violence in war and conflict is simply strategic. And not all the destruction that takes place is a consequence of territorial or geopolitical objectives. Taking over the next village, blocking a trade route or destroying the critical infrastructure that supports everyday life are the fundamentals of strategic advance but other actions are intended to undermine morale and have a psychological impact on the victim.

The degradation of the urban environment, or urbicide, is one such action. This is the destruction or desecration of buildings, the eradication of public space, the attempt to erase history and memory through attacks on libraries and sites of historical importance.

Urbicide is not just about physically removing people from a territory, it is an attempt to erase any trace of their existence in that territory. It is rewriting the history books to justify one side of an argument. This is particularly true for religious or ethnic conflicts, where one side aims to undermine the other’s right to a disputed piece of land.

Cybercide, the cyber-crime equivalent to this practice, is a relatively new concept but could prove to be an equally powerful tool as we become more dependent on digital services in our daily lives. Yet we rarely think of preparing to defend ourselves against attack in this way.

Digital disruption

Acts of cyber-vandalism are increasingly common and are used to deliver a message. They are symbolic statements that are often used to great effect.

Over a three-week period in April 2007, websites in Estonia were hit by denial of service attacks—a well-known technique that aims to debilitate an online service by disrupting the technology on which it runs, such as internet connectivity. The websites of the Estonian parliament, banks and news outlets were hit, disrupting services for people across the country.

The attacks were a response to tensions between the Estonian government and Russian groups over the relocation of the Bronze Soldier of Tallin and other issues related to Soviet-era war graves.

Estonia’s decision to move the statue away from Soviet war graves to the Tallinn Military Cemetery was seen by many as an act of traditional urbicide. The removal of the statue undermined the significance of the war grave sites and could make it easier to suggest they were never there. The denial-of-service attacks – for which a Russian official was later convicted – were an act of digital disruption. It was about attacking Estonian infrastructure and creating a nuisance in a time when people increasingly rely on websites in their everyday lives.

In another example, the Bangladeshi Cyber Army claimed that it had defaced around 1,000 websites in protest against the actions of India’s Border Security Force. The attacks began on 7 January 2013, marking the two-year anniversary of the death of a 15-year-old Bangladeshi girl at the Indian border.

The road to cybercide

Incidents like these are not full-blown cases of cybercide but they could well be seen as a sign of things to come. The attacks in Estonia and India were a nuisance but caused only temporary problems that could be resolved. The desecration of websites is more like digital graffiti, a means for those on the margins to circulate messages in public space and leave their mark. These acts may cause offence but there is no obvious permanent damage caused so they are not the same as destroying a bridge or a building. Only those unwary website owners who don’t back up their online content suffer long-term problems when attacked in this way.

Cyberspace is fast becoming fundamental to life. The web is now vital for commerce and more aspects of our lives are stored and shaped through digital culture than ever before. It’s possible that attacks like those carried out in Estonia or India or by the Syrian Electronic Army could be more permanent and severe.

In the race to digitize more and more aspects of our existence we might be failing to grasp the potential accidents and vulnerabilities on the horizon. The speed and efficiency with which we try to digitize services might limit thinking and planning on the more negative unintended consequences of technological change.

How safe are our financial details, for example? Would a group be able to delete our financial histories or—in conjunction with ethnic cleansing—erase property deeds to make it seem like certain people have no rights on land?

And what of libraries and artifacts? More and more books and music are being published digitally—sometimes with a hard copy version but sometimes without. If, in 30 years’ time, we find ourselves in the age of completely digital libraries, a whole new set of vulnerabilities is possible.

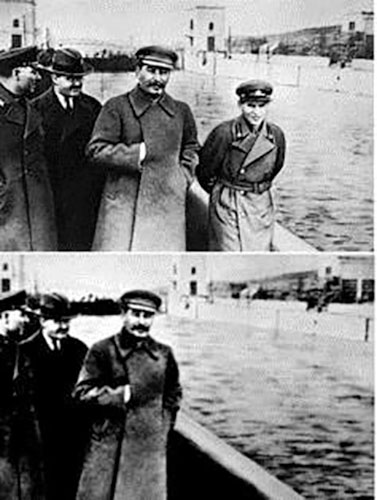

In 2009, Kindle owners who had bought the George Orwell classic 1984 woke up one day to find Amazon had simply erased the title from their devices. Hard copies still exist, of course, but which future classics do or will only exist in digital form in the future? A decision such as this by a company or a government could wipe that piece of literature off the face of the Earth. Just as Stalin used what technology was available to him in his time to repaint history, the dictators of the future might try to re-write history by altering the books stored in online national libraries.

Of course, it can be argued that the “distributed” nature of digital life provides protection. Information is distributed across too many locations to be completely erased, which protects us from the actions of states or criminal organizations that would seek to control information. Anxiety about future cybercide may well be a symptom of living in a time of rapid and disruptive social, economic and political change but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t plan for the future.

However, cybercide potentially embodies more subtle forms of social manipulation. It is relatively hard to degrade or alter the urban environment to erase a group of people or a historical artifact without anyone noticing. And yet the subversion and subtle manipulation of digitally held information is the lifeblood of hackers the world over.

What if the aim is not to destroy a whole piece of literature, but to subtly alter the text, say of a school book to change its meaning or remove passages from disputed literature. These changes may not be noticed in time to prevent them from becoming conventional wisdom or perception. They could change a whole generation’s understanding of a historic event or specific social group.

The concept of cybercide provides an infinite spectrum of disruptive possibilities to undermine morale and have a psychological impact on the intended victims. Ones that may be more subtle and seditious than we have seen before or could possibly imagine.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article. They also have no relevant affiliations. Lancaster University Provides funding as a Founding Partner of The Conversation.

By Daniel Prince Associate Director Security Lancaster at Lancaster University Mark Lacy Politics, Philosophy, and Religious Studies/Associate Director, Security Futures at Lancaster University