PBS’ drama “Resistance” is an historically based account of French underground cells that sabotaged German headquarters, military installations and other venues frequented by Nazis. These assassination-and-sabotage squads singled out German soldiers and their Vichy collaborators.

Although Lili Franchet, the fictional female lead, was created to tie the story together, the basic characters are real, as are their stories, including imprisonment and in many cases, executions. They are well-documented, beginning with the invasion of France in 1940 through Germany’s surrender in 1945. “Resistance” is spellbinding, but what resonated was that behind the saboteurs’ codenames were identifiably Jewish fighters.

I lived in France, where antisemitism was, and is still, endemic. The headmistress of our seminary revealed that after an informer betrayed her father, her mother clandestinely worked to rescue Jewish children. One of my in-laws survived because a network of Jewish youth moved her from place to place. She found refuge as a maid in a Catholic family in the “free” south of France. These accounts and much of what I have read seemed to indicate relatively isolated incidents of Jewish resistance. In fact, though, there were multiple Jewish units that successfully upended German and Vichy operations, so much so that French Israeli historian Renee Poznanski asked in a May 3, 2016 Tablet magazine article, “Was the French Resistance Jewish?”

The number of Jews who carried out attacks on Nazis and Vichy targets and were tortured and executed for attempting to free France from its oppressors seems disproportionate to Jewish presence in France. Many Jewish immigrants, or their children, united there against the Third Reich. This included men and women (some teenagers), who smuggled children to safety into Switzerland, or those who risked and lost their lives hiding them in convents and in homes in Vichy-controlled territories and the “free” south of France.

What, then, is so shocking about a critical mass of Jews participating in militias and partisan efforts, not only on behalf of their coreligionists, but also on behalf of all Frenchman who did not dance to the Nazis’ or their Vichy puppets’ tunes? It debunks the persistent myth that Jews went like sheep to the slaughter, except for famous incidents like Sobibor or the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising,

For various reasons, both for security and due to wartime French antisemitism, some French Jewish Resistance fighters kept a low profile about their Jewishness, leadership of Resistance cells, and even persecution/deportation of their family members. Nevertheless, Jews comprised 90% of the first detachment of Franc-Tireurs Partisans Immigrant Labor Party ((FTP-MOI) and 100% of the second detachment. Poznanski wrote: “In February 1943, out of 36 actions taken by four detachments of the FTP MOI [which operated in Paris], 15 were realized by the Jewish Second detachment.”

Considers the Jewish fighters of “Resistance,” who constituted a fraction of all Jewish fighters:

Andre Kirschen, tried at 15, survived 10 years in prison in Germany.

Bernard Kirschen, 21, Andre’s brother, executed.

Joseph Kirschen, Andre’s father, executed as family of a “terrorist.”

Tomas Elek-20, executed.

Leon-Maurice Nordmann, 34, executed.

Jean Frydman, 15, interrogated, deported to Buchenwald but escaped from train; survived.

Anatole Lewitsky, 38, executed.

Andre Weil-Curiel, b. 1916, escaped to London, twice, finally joined General DeGaulle.

Simone Schloss, 22, executed in Germany.

Cristina Luca Boico (b. Bianca Marcusohn, 1916) returned to her native Romania after the war.

Serge Ascher, b. 1920 (likely Jewish, unconfirmed) later headed French Forces of the Interior.

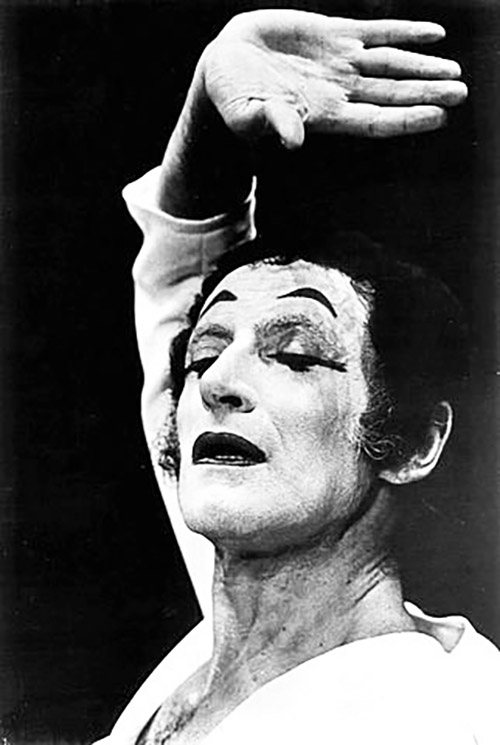

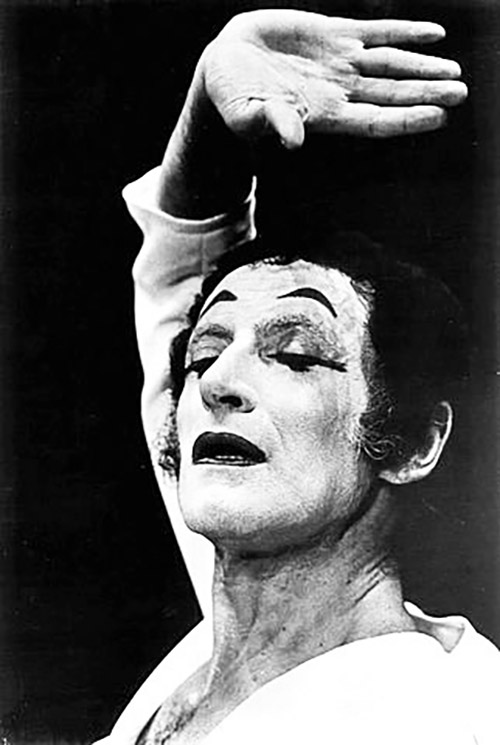

The sacrifices of these resistance fighters were complemented by other giants of the Resistance who worked behind the scenes, at enormous risk, to rescue Jewish children. Among them, Marcel Marceau, the world’s most famous mime, honed his craft.

The French (Mime) Connection

Marcel Marceau further refined the comedy and pathos of Charlie Chaplin’s work with Bip, his tragicomic clown. Marceau had a “chush,” a flair for perfecting life’s fragility through minimalist gestures and expressions that had maximum impact on audiences.

As a theater student who admired Marceau’s work, I never imagined that the man born Marcel Mangel in Strasbourg, the son of an immigrant kosher butcher and his wife, had, among other roles, forged papers for non-Jewish and Jewish youth in peril of deportation. What, though, is the connection between the Resistance and Marceau’s mime?

Marceau (then Mangel) and his family fled to Limoges, in southwest France, when the Nazis invaded France. He and his brother changed their names to avoid detection. Marceau was recruited by his cousin Georges Loinger to join the Armee Juive, which morphed into Organisation Juive de Combat (OJC). It engaged in armed struggle against the Germans. Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants (OSE), one of its units, saved thousands of Jewish children from deportation. Together with Loinger, Marceau escorted Jewish children over the perilous French border and to safety in Switzerland. Marceau himself saved at least 70 children in this manner.

As they approached the border, Marceau needed complete silence from the children. This is where his nascent mime skills were crucial. In Jewish orphanages overseen by the OSE, Marceau acted and mimed to engage the adoring children. He was able to put them at ease as they approached border crossings. In one incident, dressed as a boy scout leader, he escorted 24 Jewish children, also dressed as scouts, on an “excursion” to safety.

Perhaps Marceau’s most intrepid move, at the end of the war, was when he encountered 30 German soldiers and, pretending to be part of an advancing French contingent, demanded that they surrender to him, which they did.

After the Allies entered Paris, the multilingual Marceau became a liaison to General Patton’s army. His sadness at his father’s murder in Auschwitz was absorbed into his mime character, the clown Bip, whose universal pathos permeated Marceau’s body of work.

Marceau was awarded the French Legion of Honor for his service, and a few dramas such as “Resistance” have been produced. Nevertheless, more written and visual accounts of World War II should acknowledge Jews’ strategic, organized opposition to Nazism, to further debunk the stereotypical perception of Jews’ acquiescence to their annihilation during the Holocaust.

Visit www.pbs.org/show/resistance/ to stream “Resistance” and find out more.

Rachel Kovacs is an adjunct associate professor of communication at CUNY, a PR professional, theater reviewer for offoffonline.com—and a Judaics teacher. She can be reached at mediahappenings@gmail.com.