Paramus—Zelik and Mindl Diamond sit front row center in the Paramus High School auditorium, VIPS waiting for the beginning of the performance. Surrounded by their two adult daughters, they exude calm and grace, chatting easily with the many well-wishers who surrounded them. The play they are about to see, Diamonds in the Forest, is the story of their young lives in the horror of the Holocaust, decades back in time, light years away from the tranquility of life today, portrayed by the eighth grade students of Yavneh Academy in Paramus.

The Diamonds had asked Rabbi Shmuel Burstein, Holocaust Studies Coordinator at Yavneh, to write their story, after meeting him through his mother, their neighbor. As the manuscript progressed, Rabbi Burstein realized it would be perfect for the annual eighth grade play about events during the holocaust. The principal and others on the committee agreed. This was a story that begged to be told.

The play begins with an overview, told by three of the actors. The story arc is achingly familiar: The tenuous calm of a Polish town, with a large Jewish population living and doing business with non-Jewish neighbors, is shattered when the Germans invade and brutalize the Jewish inhabitants. After many of the townspeople are murdered, Zelik Dimenstein and Mindl Katzovich, who both lost their mothers, escape with their remaining family members and join different groups of partisans in the forest. They survive in the forest for over two years, and when the war ends, they return to their homes and find nothing to stay for. In an American DP camp, Zelik and Mindl, who didn’t know each other before, meet and begin a new life together that takes them to America.

As the drama slowly unfolds, we watch the characters take shape; we get to know their lives, their world and their dreams. We begin to feel who they are. Panels, painted by the students, portray a rural town with a synagogue as the focal point. The staging, by Dominique Cieri, who has been directing the annual play since 1995, assigns each family a part of the stage, with the public action in the middle, so we are immediately drawn into the rhythms of village life. The sound track, which blends music and sound effects, was expertly chosen by Cieri, from much research, to convey the action, including loud moos as Dimenstein, the cattle dealer, makes a purchase.

In the Dimenstein household, news of the day is discussed in heated tones. We learn that the Russians, who then controlled the town, are leaving. And the first rumors of murderous German antisemitism are breaking through.

On each side of the stage, the Dimenstein and Katzov families light Shabbos candles, showing their commitment to observant Jewish life and its centrality in their lives. Cieri told me in a subsequent interview, that the best way to convey the enormity of the Holocaust is to begin by showing what was destroyed.

Dialogue is what moves a story forward but it has to be natural. Cieri succeeds here by using verbatim dialogue from Dimenstein memoirs, and creating dialogue through careful interpretation. In one scene, as the Nazis begin their extermination plans, two young boys are digging graves. Cieri said she had asked the students to write about indoctrination—how was the younger boy influenced by the older? The young one asks whether or not it was a sin to kill. The older replies that Hitler is purifying the world; that Jews aren’t human. The younger one redoubles his efforts.

The full brutality of the war is captured in a scene that finds Zelik and his family hiding in the dark, while the sounds of bullets and screams are heard in the background. Slowly a siren builds until finally, on a pitch black stage, the slow fading of the siren is the only sound.

After the families escape, partisan life is portrayed as a mixed blessing. There is a constant struggle for food and safety. The Russian partisans treat the refugees well, leading one group to safety in Siberia. Zelik becomes sick at one point and begs his father to leave with his sisters. He recovers and finds them again. Then he is asked to rescue a group of 20 Jews in the forest and his father tries to stop him. But Zelik insists, travelling at night so he wouldn’t be seen, and saves them all. After the play, he tells several of us that he is very proud of what he did, getting them all out alive.

The drama ends when the partisans emerge from the forest to find out the war is over. Actors narrate the rest of the Diamonds’ story. They moved to Omaha, Nebraska, where they had relatives and raised two daughters, who moved to Monsey, NY. Two years ago, Zelik and Mindl followed. Daughter Leta Greenstein said, “My father retired at 90 and the next day they moved to Monsey.”

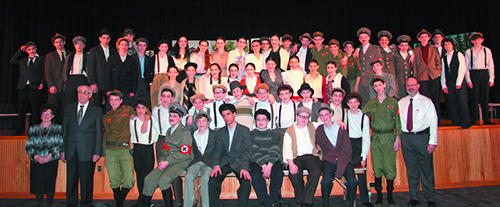

The students all performed splendidly. It was somewhat disconcerting to see students in Nazi uniforms, issuing orders to murder Jews. I asked them after the show how it felt to portray a Nazi. Gavi Brody said, “We had to act horrible and tough, to be mean enough to kill and destroy. I put on the costume and I felt evil.”

Yonaton Gordon, who gave an exceptional performance as Zelik, said being in the play was an inspiring experience. “We’re the last generation to be able to be with the survivors,” he noted.

Yavneh has been producing a Holocaust play annually for over 30 years. Rabbi Burstein, who has a Masters Degree in Jewish History, became the Holocaust Studies Coordinator 13 years ago. A requirement for the position was to take a two week course on theatre production for educators taught by Cieri at William Patterson College. With a grant from the New Jersey Council of the Arts, Cieri joined Yavneh to produce the play. “She raised it to a professional level,” Rabbi Burstein said.

While the survivors’ stories all have common elements, to be made into a play they have to have certain characteristics. “The story must be based on a book or manuscript.” Rabbi Burstein said. “It has to have character development, so the students can see the development of tension and personalities.” Students compete to write and perform. The writers have to read a story and take a test. “They don’t have to be A students but they have to show serious interest and follow through,” Rabbi Burstein said. Students who want to act, audition with a script of their choosing. Ultimately, everyone who auditions gets a part, but not everyone has to speak. And there are other jobs. Rabbi Burstein said each year there are a few students who do it all – write, perform and do set design.

The writing begins with Cieri. Once Rabbi Burstein tells her the book title, she reads it and creates an outline. “I have to look at the meat of the story, the basic elements, and identify the emergency in each scene. And answer what we call the Passover question: what makes this day different than all other days?” Cieri said. For Diamonds in the Forest, Cieri said it is when the Germans invade.

After she writes the outline, the 10-16 writers are divided into groups to work on different scenes. Along with the process of revision, she advises when they should do research to answer key questions about the story. In this play, they had to research what the town was like when it was under Russian control and how the Russians differed from the Germans. There was an additional level of difficulty with this story as it came from a historical manuscript with interviews that had to be turned into drama, Cieri said.

Cieri spends about 40 days a year from start to finish on the show. The last week gets very hectic. “Usually you have one to two weeks to rehearse with the lighting and sound. We have a day to a day and a half.”

Behind the scenes, dedicated parents, former parents and staff help make the production come together. Malky Kazam, the art teacher takes Cierei’s drawings of the set and translates them onto panels that the students paint. Costumes have been collected over the years and one former parent takes up residence in a corner of the cafeteria at lunch time measuring and fitting the students. Parents head wardrobe and make-up committees. Sometimes Cieri gets help from former students. She said alum Sam Gordon always wanted to work with lighting. Unfortunately when it was his year to do the play, the performance was at John Harms and students weren’t allowed backstage due to Union regulations. But he came back during his high school years to help and is now a lighting designer.

Cieri juggles teaching theater and writing her own plays at several venues. She teaches drama at the Greenfield Group Residential in Ringwood for boys who are incarcerated for different reasons. A group of 12 boys and staff members attended Diamonds in the Forest on Thursday evenings.

Rabbi Burstein, Dominique Cieri and the students brought history to life. And the audience all learned a little more about the people behind the statistics. For the Diamonds, seeing their story acted out reminded them not only of the horror but the good that life has brought them. Talking to several of us after the play, Mindl said, “Our father in heaven watched over me and my husband when he was sick. I thank God for rescuing us. We raised a family of God-fearing Jews. Here we are today, children, and grandchildren.” Leta Greenstein said she and her sister grew up with this positive attitude. “They talked about what happened but they were humble, they didn’t burden us. We grew up with love and laughter. We always came before them; they were very loving, very giving.”

And that’s what the Diamonds want for everyone. “I gave the kids a brachah that they should never experience anything like this, anything bad, and should have good luck,” Mindl said. Amen.

By Bracha Schwartz