Does Rabbi Eliezer ben Yaakov always win? On Ketubot 46b, a brayta records a dispute about the nature of motzi shem ra, where the new groom slandered his bride’s chastity. The Tanna Kamma (or, Sages), have an expansive view of how this situation can arise—namely, even when they hadn’t been together. Rabbi Eliezer ben Yaakov takes the biblical verses more literally, restricting it to cases when they’d physically consummated the relationship.

We rule like Rabbi Eliezer ben Yaakov. Rambam (Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Naarah Betulah 3:10) restricts the case motzi shem ra to cases of consummation. Why rule like him? As Rav Yosef Karo notes (in Kesef Mishneh; also evident in Rif), we see that the Talmud’s conclusion, as stated by (an emended missive of Rav Kahana citing) Rabbi Yochanan, accords with him. Migdal Oz (commenting on Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Issurei Biah 3:10) further explains that Rabbi Yochanan’s motivation is הֲלָכָה כְּרַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר בֶּן יַעֲקֹב שֶׁמִּשְׁנָתוֹ קַב וְנָקִי, Rabbi Eliezer ben Yaakov’s teachings are kav venaki, succinct but accurate.

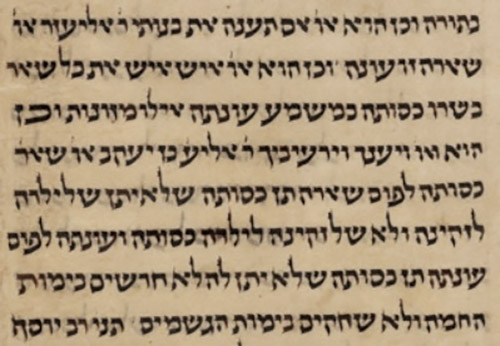

Likewise, on Ketubot 48a, Tannaim take different positions explaining a husband’s obligation to provide שְׁאֵרָהּ ,כְּסוּתָהּ and עוֹנָתָהּ. Rabbi Eliezer ben Yaakov states that he must provide her clothing (kesut) in accordance with her flesh/age (she’er) and the season (onah). The Rambam (Hilchot Ishut 13:1) rules accordingly, and Maggid Mishneh (Hilchot Ishut 12:1) says this is because his teachings are kav venaki; Kesef Mishneh (ibid) effectively concurs.

Two Distinct Sages

Having established the halachic stakes, we must realize that, as Rav Hyman explains in Toledot Tannaim vaAmoraim, there are two people by that name, and wonder about the referent in each sugya. In Mishnah Middot 1:2, Rabbi Eliezer ben Yaakov relates how, in the Temple, they found his mother’s brother asleep at his watch, and they burned his clothes. This would place him in Second Temple times. Similarly, in Yevamot 49b, Shimon ben Azzai (fourth-generation Tanna) said he found a scroll of lineages, and on it was written that Ploni was a mamzer due to adultery, that Rabbi Eliezer ben Yaakov’s teachings are kav venaki, and King Menasheh killed Yeshayah. Since this is a found scroll, it would refer to a rabbi of an earlier generation. The Rambam in his introduction lists him as a Tanna from the era of the churban.

Meanwhile, several other sources place him as a later Tanna. Bereishit Rabba 61:3 explains that after Rabbi Akiva’s 12,000 students died, he established seven subsequent students. These were (fifth-generation) Rabbi Meir, Rabbi Yossi, Rabbi Yehuda, Rabbi Shimon, Rabbi Eleazar ben Shamua, Rabbi Yochanan haSandler and… Rabbi Eliezer ben Yaakov. Yerushalmi Chagiga 3:1 details how (almost the same) seven elders, including Rabbi Lazer ben Yaakov, intercalated the year in Rimon Valley. In Sifrei Chukat 8, regarding whether only the kohen gadol processes the red heifer, he joins Rabbis Yehuda, Yossi and Shimon and against Rabbi Meir. He argues back and forth with fourth-generation Rabbi Eliezer Chasma in Pesachim 32b about terumah of chametz on Pesach. And, in Midrash Tehillim 32, he cites Rabbi Pinchas ben Yair (who was a colleague of Rabbi and a son-in-law of Rabbi Shimon), so he is late. Rav Hyman deems it impossible that we are dealing with a single exceptionally long-lived individual.

Hyman also contends the second Sage was also described as kav venaki. In Gittin 67a, the sixth-generation Tanna, Issi ben Yehuda (a student of Rabbi Eliezer ben Shamua), recounts praise of various Sages, among them Rabbi Eliezer ben Yaakov as kav venaki. Based on the partial selection of Sages, Hyman argues he’s speaking of his own generation or those he’d merited to see, for otherwise there were other Sages and praises he could have cited. Hyman then harnesses this to defend Abaye (in Eruvin 62b) from the charge of confusing the two Rabbi Eliezer ben Yaakovs and applying kav vanaki to the latter. I could counter that Issi ben Yehuda does discuss Rabbi Akiva, Rabbi Yishmael, Rabbi Tarfon and Rabbi Eleazar ben Azarya, and further crafts his brayta as a series of contrasts: one Sage is a well-stocked store and the other a full storehouse. Stylistically, even if referring to a much earlier Sage, kav venaki referring to teaching style and flour quality contrasts well with grinding much and removing little.

Disambiguating Select Sugyot

If only the former’s teaching was קַב וְנָקִי, then in each sugya he appears, we must determine which Rabbi Eliezer ben Yaakov is the referent. In Yoma 16a, Rav Huna says that Rabbi Eliezer ben Yaakov authored the Mishna of Middot, and Hyman says (based on reference to the Temple in Middot) that it’s the former. So too, whenever the topic is aspects of the Temple or its service, these are details the former Sage knew from his uncle. (Indeed, I wonder whether his Mishna being kav venaki, a small but pure measure, refers directly to Mishnayot Middot, as word play, since the topic is dimensions of the Holy Temple.) Hyman also notes we may disambiguate based on who interacts with him, e.g. when he argues with Rabbi Yishmael ben Elisha in Kelim 7:3 or Sotah 9:4 where he argues with Rabbi Akiva and Rabbi Eliezer.

Rav Hyman lists many instances involving argument or citation to establish him as the earlier or later Sage, though I might quibble. For instance, in Sotah 3a, he tags the former because Rabbi Yishmael in one brayta accords with Rabbi Eliezer ben Yaakov’s position in another brayta, implying the second brayta is earlier. But, Talmudic Narrator makes the connection—there’s no direct interaction. And, in Sotah 45b, Hyman tags the latter, since the Gemara states fifth-generation Rabbi Yehuda in the Mishna isn’t consistent with a position Rabbi Eliezer ben Yaakov takes in a brayta. Again, it’s the Talmudic Narrator’s contrast, not a direct dispute.

Hyman deems all instances of “a brayta of Rabbi Eliezer ben Yaakov’s academy” to be the latter Sage, since Rabbi Akiva’s students all composed braytot. He believes Ketubot 48a (clothing obligations) refers to the latter Sage, as Rabbi Eleazar (ben Shamua) is a disputant. This contradicts the kav venaki proposed by Rambam’s commentators. One caveat is we should ascertain his disputant is Rabbi Eleazar (as the printed text and Munich 95) and not Rabbi Eliezer ben Hyrcanus (as in Vatican 130 and other manuscripts), which would make him the earlier.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.

As a Deciding Principle

Might “kav venaki” only indicate praise? Who says it’s a legally decisive principle? Three sugyot. In Yevamot 60a, Rabbi Eliezer ben Yaakov maintains that the offspring of a Kohen Gadol who married a raped or seduced woman is a chalal. According to one report, Rav says that Rabbi Eliezer ben Yaakov accords with (fifth-generation) Rabbi Eleazar (ben Shamua), that intercourse with an unmarried woman renders her a zonah. The Talmudic Narrator objects: Rabbi Eliezer ben Yaakov’s teaching is kav venaki, plus elsewhere Rav says we rule against Rabbi Eleazar! It concludes that it’s difficult. Might we answer that kav venaki isn’t halachically binding; alternatively, this was the latter Sage, contemporary with Rabbi Eleazar?

In Bechorot 23b, Rav Nachman cites Rav that throughout the perek, the halacha accords with the anonymous Tanna of the Mishnah except where someone disagrees. Where is this statement necessary? One possibility was the preceding Mishnah (21b) Rabbi Eliezer ben Yaakov said that if a large animal expelled a bloody mass, the mass must be buried and the mother is exempt from future offspring being considered firstborn. The Talmudic Narrator rejects this possibility – Rav’s statement is unnecessary since Rabbi Eliezer ben Yaakov’s teaching is kav venaki. Here, reading the entire Mishnah chapter, the former Sage might be possible. The other Sages discussing the topic include Rabbi Akiva and Rabbi Yishmael. If the latter, we have a rejoinder.

Since the Talmudic Narrator only applies principles expressed elsewhere by named Amoraim, the third sugya is key. In Eruvin 61b, the Tanna of the Mishnah (understood by the fourth-generation Pumbeditan Amoraim, Abaye bar Avin, Rav Chinena bar Avin, and Abaye, to be fifth-generation Tanna Rabbi Meir) says the presence of a resident gentile in a courtyard invalidates the eruv, while Rabbi Eliezer ben Yaakov disagrees, unless there are also two Jews living in the courtyard. Then (Eruvin 62b) second-generation Amora Rav Yehuda (Pumbedita) cited Rav that the halacha is like Rabbi Eliezer ben Yaakov, Rav Huna (Sura) says the minhag is like him, and Rabbi Yochanan (Israel) says the nation are accustomed to act like him. In Pumbedita, Abaye asks his third-generation teacher Rav Yosef that, given (A) Rabbi Eliezer ben Yaakov’s teaching is kav venaki, and given (B) Rav Yehuda cited Shmuel that the halacha is like him, what about issuing this ruling in one teacher’s locale, something typically restricted?

The problem is that this is Rabbi Eliezer ben Yaakov II, for he argues with Rabbi Meir! Did Abaye confuse the two identically-named Sages? Rav Hyman (above) answered that kav venaki was applied to both. I’d suggest that the Mishnah’s anonymous Tanna could be other than Rabbi Meir, but earlier, Abaye assumed it was Rabbi Meir. Therefore, I’d note that (A) and (B) are flipped in Rif and several manuscripts, and that (B) is both more central to the sugya and most relevant in Pumpedita. Perhaps, then, (A) was a marginal insertion, one Abaye never said.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.