A recent theme in this column has been ambiguous people and terms. Rabbi Yochanan might be the Tanna or Amora, and chazaka might refer to six different halachic concepts. I’m going to continue this theme this week by discussing a phrase relating to Pesach.

In Yevamot 40a, a brayta juxtaposes a discussion of eating a mincha offering (which is matzah and not chametz) with levirate marriage. According to Rav Yitzchak bar Avdimi II , the levirate marriage section considers two means of accomplishing yibum, and directs one to accomplish it only with intent to fulfill the commandment. By analogy, the mincha section should have two means of consuming it, directing one to select a particular path. The Gemara considers that the two methods would be eating with an appetite (לְתֵאָבוֹן) and eating gluttonously (אֲכִילָה גַּסָּה—forcing oneself to eat), with the former being the required method, but rejects it because אֲכִילָה גַּסָּה is not even deemed eating. Resh Lakish exempts one who eats gluttonously on Yom Kippur from the karet-bearing injunction of לֹֽא־תְעֻנֶּ֔ה, “who does not afflict ”—since he is מַזִּיק, harming himself rather than enjoying .

Tosafot note a contradiction with Nazir 23a. Rabba bar bar Chana said that Rabbi Yochanan interpreted a verse in Hoshea homiletically. “For the paths of the Lord are right, and the just walk in them, but transgressors stumble over them.” How do two people take the same path but one stumbles? Imagine two people roast their korban Pesach. One eats it on Pesach night with intent to fulfill the precept while the other eats it gluttonously—אֲכִילָה גַּסָּה. Resh Lakish objects to him: Would you call this person a rasha/transgressor? True, he didn’t fulfill the precept optimally, but he still has fulfilled! We thus see that one fulfills with אֲכִילָה גַּסָּה and, we might add, both are expressed by Resh Lakish. Tosafot suggest that there might be two meanings of אֲכִילָה גַּסָּה. Tosafot in Nazir elaborate that in the invalid one, because he’s so stuffed, he’s forcing himself to eat but is disgusted, but the אֲכִילָה גַּסָּה in which he fulfills, he’s merely not hungry, so doesn’t eat לְתֵיאָבוֹן, with appetite. Both are improper, but in one case he fulfills. See also Pesachim 107 and 120, about not eating matzah gluttonously, and consider which is intended based on textual cues.

However, see Rashi’s explanation in Nazir of לְשֵׁם אֲכִילָה גַּסָּה. He writes אוֹ מֵחֲמַת תַּאֲוָה שֶׁאָכְלוּ בִּרְעָבוֹן, “or because of desire, that he eats it hungrily.” The implication is about intent, to fulfill the mitzvah vs. to fill his belly. Compare with the parallel sugya (with the same conversation) in Horayot 10b, where Rashi explains אֲכִילָה גַּסָּה as שֶׁלֹּא לְשׁוּם מִצְוָה אֶלָּא נִתְכַּוֵּן לְאָכְלוֹ לְשָׁם קִנּוּחַ סְעוּדָה, that he doesn’t intend to fulfill the precept but to eat it as a dessert. Tosafot HaRosh there takes extreme exception to this incomprehensible Rashi, based on halachic objections, such as that eating it at the end of the meal—קִנּוּחַ סְעוּדָה—is the primary mitzvah, that he eats it עַל הַשּׂבַע. But Rashi is undoubtedly correct, and his detractors misunderstand his intent.

A critical component of understanding Gemara is recognizing genre. There’s a difference between halachic legal argumentation, interpretations of Scripture, aggadic narrative, and inspirational homiletics. In my field of NLP—natural language processing—it is similarly important to detect genre, e.g., news, medical text, fiction, essay, and a language model for one genre may differ from another, and words have different implications in each. This Nazir/Horayot sugya is homiletic, and by אֲכִילָה גַּסָּה, Rabbi Yochanan doesn’t intend the technical halachic term! Rashi explains that it is a matter of intent. If he doesn’t have kavana (intent) to fulfill the precept, but just to satisfy his hunger or to have a tasty dessert, then that is acting like a glutton, in nontechnical, common parlance . Similarly, when Rashi refers to קִנּוּחַ סְעוּדָה, he speaks of intent to eat a tasty dessert, not where it is structured in the meal.

Tangentially, we might point to Yevamot 106a, where Rabbi Yochanan and Resh Lakish disagree about mistaken chalitza, which a brayta declares valid. Resh Lakish explains that it was performed in error, where the yavam, not well-versed in halacha, believed that he was thereby marrying the yevama. Rabbi Yochanan objects that everyone’s intent is required there. While the dispute is primarily about whether chalitza is akin to yibbum in requiring intent, it forms a nice parallel dispute about whether precepts require intent to be valid, with Rabbi Yochanan more demanding of intent.

Regardless, at the Seder, we want “glutton-free” matzah, with all three aforementioned meanings. I think this is easy since I believe (controversially) that the actual fulfillment is the earliest matzah—but that would require a separate lengthy column. It’s harder if you’re fulfilling with the afikoman, after stuffing your face with enormous kezayit shiurim of matzah, maror, korech, and then shulchan orech, all before chatzos, and also requiring consumption within nine minutes7. This pits various chumrot against fulfilling the primary precept of אֲכִילָה. Also, understand that the rasha of the Seder removes himself from the community and doesn’t participate. As per Resh Lakish, anyone at the Seder, of whatever religiosity and intent in being there, cannot be called wicked.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.

1 This is the third-generation Babylonian Amora, a generation before his fourth-generation disputant Rava. It isn’t Rav Yitzchak bar Avdimi I, a first-generation Amora who was a tanna (reciter of Tannaitic material) in Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi’s yeshiva.

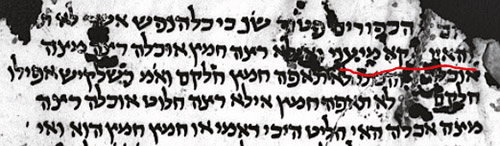

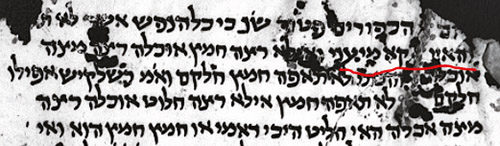

2 I would suggest because this indeed is affliction. Indeed, the St. Petersburg manuscript of Yevamot has והאיי קא מיעני, “and this one is afflicting.” And Rab. 1623 to Yoma 80b also has והא קא מיעני. Other manuscripts disagree, however.

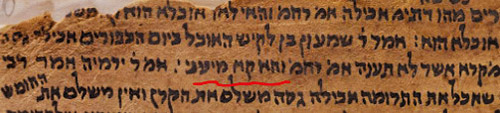

3 In the parallel from which this is drawn, Yoma 80b, Rabbi Yirmeyah then cites Resh Lakish (or variantly, Rabbi Yochanan) that a non-kohen who eats terumah via אֲכִילָה גַּסָּה pays principal but not the 1/5 penalty, for the verse states כִּי יֹאכַל, to exclude one who is מַזִּיק. Similarly, he cites Rabbi Yochanan that a non-kohen who chews barley terumah only pays principal, again because כִּי יֹאכַל excludes one who is מַזִּיק. The latter portions of the textual parallel seems a better prooftext, that it isn’t even deemed eating.

4 Rav Steinsaltz has Resh Lakish (second-generation) object to Rabba bar bar Chana (third-generation), but Artscroll’s correct that he objects to his contemporary, Rabbi Yochanan. Rabba bar bar Chana is citing the entire exchange, and isn’t the conduit of Rabbi Yochanan’s opinion to Resh Lakish!

5 Rav Schachter notes that some Tosafot are briefer than others, so when you see a citation such as נזיר דף כג. ושם, the “vesham” means a Tosafot there elaborates, and might provide more details.

6 Rashi would then disagree with Tosafot about the existence of two bad levels.

7 See also Rabbi Yair Hoffman’s article, “The Forgotten Method of Eating Matzah” in The Five Towns Jewish Times or Yeshiva World, where he writes, “Place both kezeisim in the mouth together. Both kezeisim are then chewed well and split, within the mouth, in half—one kezayis on each side. Then one is swallowed, followed by the other.” This is ideally performed within two minutes. I think that this is surely not a forgotten method that our ancestors performed, but a legalistic combination of stringencies that takes us more toward the artificial אֲכִילָה גַּסָּה end of the eating spectrum.