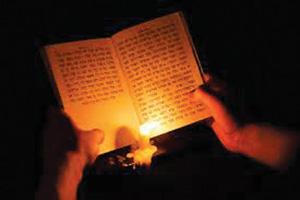

Parshat Devarim

Shabbat Chazon

“Chazon,” the word that opens our haftarah and, therefore, the entire Sefer Yishayahu, is one of 10 synonymous terms for “prophecy.” But, as Rashi points out, it is the most harsh of the terms, a word that introduces a message of strong and cutting rebuke. It is, for that reason, a most fitting word for this pre-Tisha B’av reading. But it is also fitting for the opening of the prophet’s book, as his visions are often replete with stinging messages from God.

In truth, the words of admonition had to, by necessity, be biting and intense. As Rav Shimshon Raphael Hirsch remarks, the nation looked around them and saw that things were fine. The Temple stood and the sacrifices were offered daily; kohanim and leviyim served as they should; a king from the Davidic line still occupied the throne and there were prophets and there were scholars. With all of this happening, it was difficult for the people to believe that Hashem was angry with them and ready to exile the nation. The task that Yishayahu faced was a monumental one. With all things seeming to be the same as always and with much success to convince the nation that Hashem blessed them because they had remained fully faithful to God’s commands, the prophet’s words fell on deaf ears. It is, after all, only human nature to see the good in oneself and to regard predictions of doom as murmurings of a madman. To awaken them from their self-induced lethargy, Yishayahu prophesies with “chazon,” harsh and biting words.

We may rightfully ask why the navi condemns the entire nation. After all, there were righteous, there were the scholars, there were the prophets. Were all of them evil and deserving of punishment? The answer is…perhaps; that is, all may not have been evil but, nonetheless, all deserved punishment. Allow me to explain.

When one is witness to the immorality that the haftarah details, i.e., justice that is corrupt, leaders who steal from the people, officers who take bribes and a population that oppresses the weak, the orphan and widow—when one is surrounded by this behavior and remains silent—he too is deserving of punishment. The rabbis of the Talmud declare “shtika k’hoda’ah”—silence is tantamount to agreement (literally silence implies an agreement to the truth of that which was done or said). And when the good and righteous do not cry out against the immorality and the corruption, then they are not good and righteous!

And it is precisely for this reason that Hashem condemns all of the people. Part of our task as a mamlechet kohanim, a nation serving God, is that we create a society that feels responsible for others. Such a society must correct mistakes, straighten the crooked and direct those who wander off Hashem’s path. It is a task that requires tact, warmth, understanding and, sometimes, harsh words.

Speaking out against injustice and immorality may sometimes include “chazon.”

But it is far more preferable than having to cry “Eicha” when it is too late.

By Rabbi Neil N. Winkler

Rabbi Neil Winkler is the rabbi emeritus of the Young Israel Fort Lee and now lives in Israel.