A group of guys walk into a college dining hall. They probably get a few head-turns, but not too many. Almost everyone knows who they are. If their faces weren’t recognizable, their gear gives them away.

They are the baseball team. Though it’s just ramping up this time of year, the Wake Forest University campus is already excited for baseball. This season’s preseason poll has 14 of the top 25 teams located in the south, and much like a few dozen cities in the

region, this school takes baseball pretty seriously. While it may not be a big sport on national television, weekend conference match-ups are huge events in the spring if you’re south of the Mason-Dixon line.

Everyone wants their team to succeed. But in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, it’s been a few years since they were truly great. In 2017, they went to the final game of a best-of-three Super Regional before bowing out; just one game short of being one of the eight lucky teams to make it to Omaha, Nebraska, for the College World Series.

Four seasons removed from that high, everyone can’t wait to return to glory. And in college, that means recruiting. Though there are four graduate students who played elsewhere before, this year’s team doesn’t have a single senior on the roster. What they do have is 13 freshmen straight out of high school. Their recruiting class was ranked 13th in the country, their best position ever. Two of those freshmen were good enough to be drafted by Major League Baseball teams last year, but declined to sign contracts in order to come to Wake to play in college.

One of those two freshmen breaks away from his teammates as they enter the dining hall. His food is not the same as what his teammates, or anyone else in the dining hall, will be eating. And he’ll wash his hands and say a blessing before he takes a bite of his sandwich.

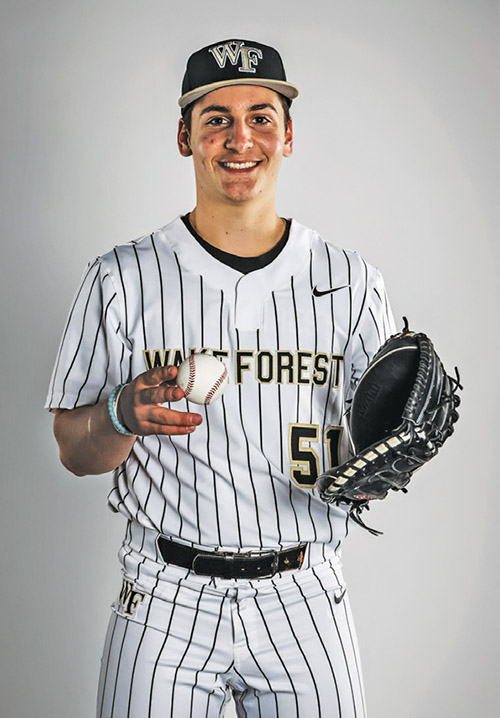

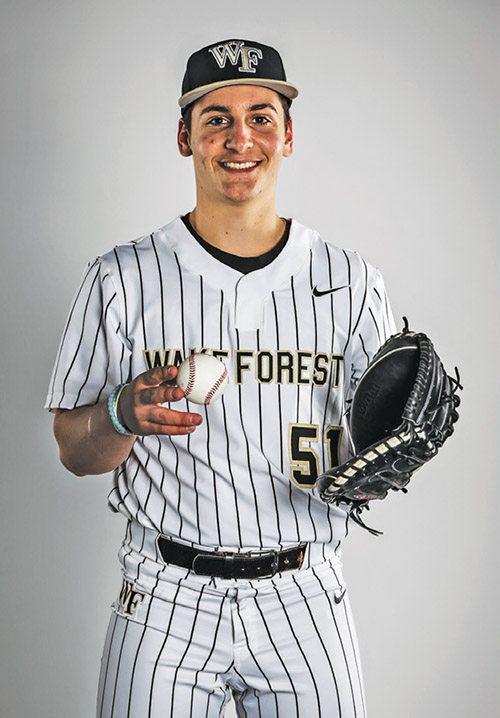

Elie Kligman grew up with baseball.

While that might be said about many Jewish kids who love America’s pastime growing up, it’s a little bit different in the Kligman household. That’s because Elie’s father, Marc, has a job that’s a little bit different from most typical Jewish lawyers … he’s also a Major League Baseball Players Association certified agent.

Growing up, Marc had played college baseball himself before hanging it up in favor of coaching. While his connections as an agent in baseball were certainly helpful, the other important part of Elie’s baseball development was Marc’s coaching. That was the case even before Elie was old enough to play on teams that his father coached.

Marc has dozens of clients all over baseball. Some of those clients end up dropping by here or there. Others show up for a bar mitzvah or two. Needless to say, having a big leaguer around every once and a while isn’t bad if your goal is to make it there yourself someday. And if you think that’s a lofty goal, tell that to Elie Kligman.

“My goal has been the same forever,” Elie says. “To play in the major leagues.”

They say you’ve got to start somewhere. Elie grew up in San Diego, California, and started in tee-ball, just like every other six year old kid out there. From there he played in little leagues and pony leagues for the next several years. After moving to Las Vegas, Nevada, it was time for travel teams until he got to high school.

Around the time of some of those travel teams, it became clear that Elie might have a future in baseball. Due to youth baseball being played on varying size fields depending on the age of the players, it’s not easy to determine which kids really have what it takes for the next level as early as you can tell in other sports.

But when the bases were moved to the regulation 90 feet apart, Elie continued to thrive. At that point, the Kligmans had to make a choice about whether or not to give Elie the opportunity to make his dream come true.

When stated that way, it sounds like an obvious choice. But that’s likely because, for orthodox Jews, the path of a professional athlete is pretty alien in every conceivable way. That said, the Kligmans made the call to put Elie in position to pursue his passion.

With no established orthodox Jewish high schools in Las Vegas at that point, it was time for Elie to make some changes. Having previously attended Jewish day schools in both San Diego and Las Vegas, Elie’s formal Jewish education was coming to a close. The Kligmans were going to customize Elie’s schedule to fit all his obligations.

This meant waking up early enough to be able to put on tefillin and daven; something that would’ve been impossible for him to do if he had enrolled in the local public school. Elie started school online, which allowed him to alternate his many different activities throughout the day. He was able to shuffle his schedule as needed between praying, eating, school work, Torah study and baseball.

As the rules allowed home schooled students to play for the high school sports teams of their zoned public schools, Elie played for Cimarron-Memorial High School. Luckily for Elie, the Spartans are no joke. With a head coach who had already led the team to two state championship games, Elie was in good hands.

By senior year, Elie had thrown a no-hitter as a pitcher, was an outstanding shortstop and was transitioning to playing catcher. He was ranked the 14th best player in the state of Nevada. His progression towards Major League Baseball was moving along.

Figuring out which college to attend is hard for many high schoolers. But the Kligmans were faced with more factors than the average family. Elie was a highly desirable recruit. Or was he?

“I think there were a lot of colleges that just didn’t talk to me at all because of my obligations,” Elie said without any resentment. “There were never really any teams that I had talked to that wouldn’t continue to recruit me because of it. I think some people just didn’t recruit me in the first place.

“In terms of colleges ending up on a list, it had to do a lot with the coaches, the culture of the program and how I’d fit in both religiously and in baseball.”

Then, in July, he was drafted by the Washington Nationals.

It’s at this point where the Kligmans faced a decision that few have to make and that they might not even have anticipated. Very few high schoolers listed at catcher are even drafted. There were only eight last year.

“I have to say that it meant a lot,” said Elie about the honor of hearing his name called. “That’s the dream from day one, to get drafted and eventually play in the major leagues.”

Draftees have time to think about their decision over the summer. But Elie’s summer was a little more eventful than your average high school graduate’s. He was traveling around the United States playing with the Israeli National Baseball Team.

“It’s always a fun experience, when you’re playing with big leaguers and you’re representing the country of Israel,” said Elie about a summer most kids would trade anything for. “I made a lot of connections and met a lot of new people. Hopefully I’ll play with them again down the road, especially in the coming summers and in the next Olympics.”

Some of the players that Elie met were able to provide different viewpoints on getting drafted and whether or not to accept. It helped him greatly to be with a group of older players who had walked the path themselves.

“We felt like it doesn’t do anybody any good if you go and sign a pro contract and you’re not really ready,” Marc said in a very practical tone given that the prospect in question is his own son. “A player could

hit .180 and not develop how everyone thinks. It happens all the time. It doesn’t make a lot of sense to go into pro ball even if they’re willing to sign you, if you don’t think you’re in the best position to succeed.”

Elie might have been able to grab a high five-figure signing bonus and tried to make it through the minor leagues. But instead, he decided to decline the offer to instead pursue a path in college baseball.

Deciding to play college baseball is a big move if you don’t play on Shabbat. College baseball schedules are pretty much standard across the country. Most weeks, a team plays a weekend series plus one game in the middle of the week. That weekend series is the hurdle.

The series usually means games on Friday, Saturday and Sunday. Depending on the time of year and the time of the games, not playing on Shabbat likely means missing at least one, but most of the time two, of those games.

Compared to the daily games on the schedule for professional baseball, college would entail a much higher percentage of missed games. But that wasn’t going to stop the Kligmans from making what they believed to be the right call.

“Even though the college schedule may be more difficult, what better way to prove that anything can be done than to go through the hardest, most challenging endeavor?” said Marc, who clearly thinks Elie is up for the challenge. “Maybe Hashem is guiding us in this direction because if Elie can prove that he can do it at the collegiate level with those other additional challenges. Maybe it’ll be easier to transition to the pro level because of the scheduling where they play every day.”

“I considered it a little bit,” Elie said simply. “But in the end, I just decided that going to Wake Forest was the best thing for my development.”

Besides, who says that the college baseball schedule can’t be changed?

Back in his youth baseball days, Elie once switched leagues after one wouldn’t accommodate games not being on Shabbat and the other would. But even then, his team had to play a playoff game on Shabbat without him. After they lost the game, the team came to his house to tell him everything that happened. Even though he missed the game, having his teammates come over meant a lot to Elie.

In high school, his coach was able to schedule their games to not coincide with Shabbat. They once had a slight mishap that led to a game being scheduled on the last day of Passover. After much debate, the game was moved to the next day.

Is Wake Forest scheduling their games around the Jewish calendar? Not entirely, but the seeds are there. Their scrimmage games in the fall were pushed to Saturday night instead of their usual Saturday afternoon time slots. Maybe the better way to answer the question is… not yet.

“The big thing that everyone has to understand is that coming in as a freshman to a Power 5 school,” Marc explained, referring to the five most powerful conferences in college sports, “it’s not easy no matter who you are. There are plenty of kids who get drafted every year and turn it down, or who are All-Americans and go to a Power 5 school and they don’t play a lot the first year. Elie first has to earn it.

“He has to prove that he’s good enough so that he’s the choice over others to help the coach win. That’s what it all comes down to. Once he proves that, I think they’ll change games because they’ll want him on the field. And I don’t think it’s a big ask. You’re asking the other school once during the season to show up a little earlier on the field on Friday and to show up a little later on Saturday.”

This appears to be the biggest change in the Kligmans’ thought process. When Elie was growing up, some of his travel baseball tournaments would have to be on the Sabbath. At the time, the Kligmans just hoped that he could play on teams that were good enough to win without him. They didn’t want any resentment to fall on Elie or the family because of their observance.

It would seem that the tables have turned and they now need the university to think that the team needs Elie to improve their chances of winning. If that’s the case, it could lead to schedule changes, greater opportunity for playing time to showcase his skills, and therefore a better chance of achieving his goal.

How’s Elie dealing with the idea of playing the biggest season of his life, but missing almost half of the games? Just like he deals with everything. By thinking positively and having some faith.

“I think that this is all kind of a new experience, and not just for me,” Elie said with his trademark optimism. “I’m not 100% sure how it’s going to work out, but I’m sure that it will.”

And some of the details are very much still being worked out. Weekend road trips, for instance.

“When we see which trips he’s going to travel on, if not all of them, I’ll assist the coaching staff as much as needed to figure out the logistics of it all,” said Marc, now a veteran of planning these situations. “He’d like to be at as many games as possible that are on Shabbat, even if it’s just to cheer on his teammates and be part of the team and to watch and learn. When it’s feasible, he can walk to the game and just sit there and watch. When it’s not feasible, it doesn’t make any sense for him to sit in a hotel room all alone. We’ll send him out to an observant local community so he can have a nice Shabbat.”

Sounds like a pretty interesting set of arrangements. What kind of coach would be willing to participate in this kind of thing?

“It has to start with the coaches because the coach is going to drive the bus,” Marc said about the Kligmans’ situation. “I had a relationship with (Wake Forest Head Coach) Tom Walter for a long time. He’s just an amazing human being. He’s tracked Elie since he was younger.”

Marc isn’t exaggerating when he says that Walter is an amazing human being. In fact, Walter has the hardware to prove it.

After coaching at both the University of New Orleans and George Washington University, Walter was handed the reins at Wake Forest in 2010. Going into his first season, he had a recruit named Kevin Jordan. Before coming to Wake, Jordan was diagnosed with AMCA vasculitis. The disease severely affected his kidneys, he needed a transplant and nobody in his family was a match.

Walter got tested, matched and gave his player a kidney. After Jordan graduated, he (a black man) and Walter (a white man) started a charitable foundation called Get in the Game. Their mission is to “enhance cross-racial communication for students aged 13-24 by creating programs which incorporate peer-to-peer learning, group activities, and multimedia tools to enable young students to engage in important conversations about racial equity.”

For these actions (both the kidney and the charity) Walter was awarded the Stuart Scott ENSPIRE Award which “celebrates people that have taken risk and used an innovative approach to helping the disadvantaged through the power of sports.” According to ESPN, recipients of the award “personify the ethos of fairness, ethics, respect and fellowship with others.”

If Walter was willing to give a recruit a kidney, giving a roster slot to a recruit who can’t play on Shabbat would seem like no big deal.

So, Elie was headed off to Winston-Salem, North Carolina, to play for the Demon Deacons (not the most Jewish mascot). The next stop in his journey was going to be rather interesting.

How’s Jewish life in Winston-Salem?

“Probably a lot better than a lot of people think,” Elie said after spending his first semester there. “There’s a great Chabad rabbi at Wake Forest who’s done a lot for me, especially with food and all that kind of stuff which really isn’t available in Winston-Salem. We get like 25-30 people at Friday night dinner. We had a minyan for the high holidays. It’s been a positive experience.”

While Chabad helps out a lot with his Shabbat and holiday needs, the university itself has accommodated Elie in impressive fashion when it comes to the daily grind of feeding a college athlete.

“Wake Forest University really stepped up,” Marc said. “They wanted him to be fed and they wanted to help in that endeavor. They wanted to give him the experience of eating in the dining hall with the other kids even though none of the food was kosher. So we had a meeting with them. I didn’t think they would really do this because I thought it would be too expensive, but they agreed to order pre-made meals from Charlotte. Elie has his own cabinet in the dining hall. It has a lock on it. He’s got his own refrigerator, freezer, and microwave convection oven.

“So when he goes with his buddies to eat at the dining hall, he just pulls it out, sticks it in the microwave, and sits and eats with his friends. He doesn’t have to worry about his food, just like the rest of the kids.”

Just like moving games for Shabbat, the Kligmans have found that if you just state your requirements as a fact, people might try to accommodate you more than you’d think.

Part of that is trying to teach people about orthodox Judaism. Nobody expects a college baseball team in the south to be aware of the finer points of orthodox Judaism..

“In some ways it would be nice to have some other orthodox Jews, especially with Shabbat,” said Elie of his unique situation. “But I’m able to relate to a lot of people around school so I haven’t had trouble connecting with people.

“There’s actually a couple of Jews on the team so they obviously knew some stuff. There are kids from New York that have obviously been engrossed in Judaism just by their environment. And then there’s also kids on the team that have never really met a Jew before. So, I’d say all of their knowledge has probably increased since I’ve gotten there. They’ve all been super receptive to it and interested, so that’s pretty awesome.”

What about on the baseball diamond?

Elie’s transition to catching seems to be going nicely. Though the roster has him listed as both catching and being a utility man, catching seems to be the way he’s going from here on out. But Elie is used to playing all over the place. In high school, he played pretty much everywhere at one point or another.

“I guess the goal is to play as much as I can and help us win,” Elie said.

But catching is hopefully where his future lies. And catching offers something that most other positions don’t; shabbat would be a much more manageable issue.

Catching is a skill that’s extremely tough and takes years of practice. That’s something Elie doesn’t currently have. The first thing you need is a strong arm to keep baserunners in check. Luckily for Elie, his pitching background will solve that issue. But perfecting the “art” of catching is going to take some time.

Communication with pitchers is key and Elie should have the time to develop that over the next three or four years at Wake Forest. He won’t be eligible for the draft again until after his junior season in 2024. If by then he’s a successful college catcher, he will have a really good chance to be drafted again.

“We’re very grateful that the Nationals wanted to draft him,” Marc said of an amazing accomplishment that they essentially have to treat as a mere stepping stone. “We hope that everybody will be wanting to do that again even more so three years from now. College catchers fly off the (draft) boards.”

“If Elie were to catch one to two games a week as a freshman, I know he wouldn’t be satisfied with that. But if you take a step back, as a freshman coming into a Power 5 program, playing one to two games a week is actually pretty good.”

When Elie was pitching in high school, the Kligmans considered going down that path. But a starting pitcher throws every five days, not every seven, so eventually the arrangement would wreck the team’s rotation of starting pitchers. And it’s already hard enough for managers to negotiate all the arms in the bullpen without having to deal with the idea that one of their pitchers is always unavailable in games where he might be needed.

Catching is also extremely taxing on the body, specifically the knees because of the crouching position they spend so much time in. Because of that fact, catchers are usually given one or two days off per week. A day of rest, if you will.

Sounds perfect for an athlete who needs to keep the Sabbath.

With more orthodox athletes than ever before, the Jewish community is abuzz. Jews love sports, but mostly from afar. If Elie makes it to the big leagues some day, you can be assured that the Jewish community will make a big deal out of it.

Recent rule changes have allowed college athletes to sign marketing deals for themselves in exchange for their name, image, and likeness (NIL). Is Elie the next big spokesperson in the Jewish world?

“There are some Jewish companies that we’re talking to,” Elie said with a laugh. “Stay tuned for that.”

Whereas the very recent trend of orthodox athletes trying to go pro is certainly exciting, it doesn’t appear the Elie’s circumstances are able to be easily duplicated.

“I’d have to say my dad was a big part of how I got here today,” Elie said of the man right next to him. “Working with a lot of his players and the knowledge he has about baseball was a big part of me developing at a younger age and as I got older through high school.”

So obviously having a sports agent as your dad helps. But according to Elie, there are other factors that are also paramount to progressing along the path to the pros.

“The biggest thing is to set your goals, work hard and know that it’s possible. There are obstacles obviously, but if you’re good enough and work hard enough you can make it happen.”

Once again, there’s that optimism of his.

A guy runs up the stairs into a dugout. He gets an immediate head-turn from everybody in the dugout. Everyone knows who he is. He’s carrying his gear.

He is the team’s catcher, but he’s late because it’s a Saturday night and the Sabbath just ended. The World Series waits for no man, and this man can’t wait for the World Series.

It sounds like a dream, but sometimes dreams become reality.

Nati Burnside lives in Fair Lawn and is a man of many interests. The opinions expressed in this piece are his own, but feel free to adopt them for yourself. In fact, he encourages you to do so.