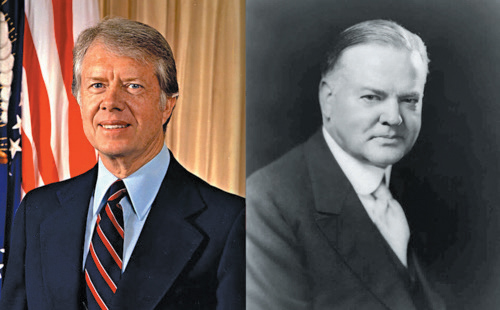

Ex-presidents seldom take an interest in Jewish affairs, with two notable exceptions. One is Jimmy Carter, who has repeatedly clashed with the Jewish community. Another is Herbert Hoover, an unlikely ally of the Jews who passed away 50 years ago this week (Oct. 20, 1964).

Most ex-presidents have gone quietly into the sunset, and some have taken issue with the few who have chosen to speak out on current affairs. George W. Bush, for example, last week had some strong words in reaction to fellow ex-president Carter’s public criticism of President Barack Obama’s Mideast policies. “To have a former president bloviating and second-guessing is, I don’t think, good for the presidency or the country,” Bush said.

Much of Carter’s post-presidential activity has revolved around Israel. He has repeatedly taken controversial stands, such as comparing Israeli policies to apartheid, urging the U.S. to withhold aid from Israel to force it to change its positions, and praising Hamas as “a legitimate political actor.”

Douglas Brinkley’s 1998 book, The Unfinished Presidency: Jimmy Carter’s Journey Beyond the White House, furnished some embarrassing details about Carter’s relationship with the late Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat. According to Brinkley, Carter “developed a fondness for Arafat” based on his belief “that they were both ordained to be peacemakers by God.” The former president went so far as to personally draft a speech for Arafat that he hoped would “help him to overcome the deficit understanding” for him in the West.

By contrast, Hoover, as ex-president, repeatedly took positions favorable to the Jewish community–even when it was not in his political interest to do so.

In early 1933, Jewish leaders asked president-elect Franklin D. Roosevelt to join Hoover, the outgoing president, in a joint statement deploring the mistreatment of Jews in Nazi Germany. Hoover agreed to do so; Roosevelt declined. Before leaving office, Hoover instructed the U.S. ambassador in Germany, Frederic Sackett, “to exert every influence of our government” on the Hitler regime to halt the persecutions. But FDR soon replaced Sackett with William Dodd, and instructed Dodd that while he could “unofficially” take issue with Nazi Germany’s anti-Semitism, he was not to issue any formal protests on the subject, since it was “not a [U.S.] governmental affair.”

Hoover publicly endorsed the 1939 Wagner-Rogers bill to permit 20,000 German Jewish children to enter the U.S. outside the quota system. He also assisted the sponsors of the bill behind the scenes, by pressuring wavering members of the House Immigration Committee to support the measure. The endorsement of the only living former president gave the bill a significant boost.

He likely would have been able to accomplish more for Wagner-Rogers if not for some unfortunate partisan sniping. James G. McDonald, chairman of the President’s Advisory Committee on Political Refugees, believed the ex-president could rally important support for the effort. He suggested “that Mr. Herbert Hoover might assume leadership in raising funds and in administering the work of placing the children in suitable homes.” But Roosevelt administration officials blocked the proposal.

It is worth noting that Hoover’s stance on the bill ran counter to his own political interests, since he hoped to win the GOP presidential nomination in 1940, and most Republicans (like most Democrats) opposed increased immigration. Moreover, since Roosevelt was enormously popular in the Jewish community (he won about 90 percent of the Jewish vote in the previous election), Hoover had little reason to think that supporting Wagner-Rogers was going to win Jewish votes.

During the Holocaust years, Hoover associated himself with the activist Bergson Group, which lobbied for U.S. action to rescue Jewish refugees. He served on the Sponsoring Committee of Bergson’s protest pageant, We Will Never Die. The former president was also honorary chairman of Bergson’s July 1943 Emergency Conference to Save the Jewish People of Europe, and addressed the event via live radio hook-up.

Additionally, Hoover played a significant role in the decision to include a plank in the 1944 Republican Party platform urging the rescue of Europe’s Jews and supporting Jewish statehood in the British mandate of Palestine. It was the first time in American history that major political parties took such a stand and it forced the Democrats to adopt similar language at their convention later that year. As a result, support for Zionism and Israel became a permanent part of both parties’ platforms and a cornerstone of American political culture–and has remained so, even when challenged in recent years by another ex-president.

Dr. Rafael Medoff is director of The David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies, (www.WymanInstitute.org).

By Rafael Medoff/JNS.org