Are you fascinated by medieval castles and “Outlander”-style adventures? Interested in sampling different whiskys or simply want to take in the natural beauty of a lush, green country, but concerned you won’t be able to find a place to daven and keep kosher? Scotland may be a great destination for the summer and beyond.

The Jewish population of Scotland—officially a legal jurisdiction of the United Kingdom, which also comprises England, Wales and Northern Ireland—is primarily concentrated in Glasgow and Edinburgh, with smaller communities in Aberdeen and Tayside and Fife. It has remained pretty stable over the past decade; according to published figures from the country’s census in 2022, the latest count, the number of self-identified Jews dropped by 40—from 5,887 in 2011 to 5,847 in 2022.

This figure is down from Scotland’s peak figure of 25,000 in the 1950s and 1960s, said Michael Tobias, a Glasgow resident and community leader who is president of the Jewish Genealogical Society of Great Britain and an unofficial walking encyclopedia of the community’s history.

While the Jewish community is younger than others in Europe, Jews have lived in Scotland since the 1700s, with the first formal Jewish community dating back to 1816 in Edinburgh, with about 20 families. Numbers remained small until the late 1800s, with about 2,000 Jews in Glasgow in 1890, and about 7,000 a decade later, according to the Scottish Council of Jewish Communities, which published “Scotland’s Jews: A Guide to the History and Community of the Jews in Scotland” in 2008. The community grew to around 20,000 during the 1930s and 1940s, with the last phase of immigration driven by the flight from the Nazis before and during World War II, including hundreds of children who came to Scotland on the Kindertransport.

While Jews came from Germany and Holland in the early days, from the 1860s immigration gradually shifted to include Jews from Russia and Poland who were passing through Scotland on their way to the United States—with many ending their journey in the UK due to difficult conditions. Numbers began declining in the 1960s, as more Jews began moving to England’s London and Manchester, the United States, Australia and Israel.

Not only did Jews successfully integrate into Scottish society, they created their own official tartan pattern—the storied coat of arms representing different clans and geographic areas—registered under the (official) Scottish Tartans Authority. The Jewish tartan features a navy background with bright blue and white lines representing the Scottish and Israeli flags, as well as a central group of lines that represent the gold of the Ark of the Covenant, the silver of the Torah and the red of Kiddush wine.

The Glasgow area is home to the country’s largest Jewish community, with most Jews living in East Renfrewshire on the city’s south side. There are four synagogues in Glasgow, three Orthodox and one Reform; a mikvah; and a kosher market and restaurant. Scotland’s only Jewish day school, Calderwood Lodge Jewish Primary School and Nursery, in Glasgow, has adapted to demographic challenges by sharing a joint campus with St. Clare’s Catholic Primary School. Calderwood also has a significant number of Muslim and Christian students as well as children of no religion.

The 37-acre Glasgow Necropolis on Castle Street is a fascinating cemetery established in 1831; built in the Classical Revival architectural fashion, it contains around 3,500 tombs and 50,000 burials. The first burial in the Necropolis in 1832 was of a Jewish man, Joseph Levi, and there were 57 burials in the old “Jews Enclosure” between 1832 and 1855. Not as visually interesting but also historic is the Glenduffhill Cemetery on Hallhill Road, the largest Jewish cemetery in Scotland with some 8,000 burials, including war graves.

Scotland’s Jews, like their counterparts around the world, have experienced an uptick in antisemitism since the outbreak of the Israel-Hamas war, with 68 recorded antisemitic incidents in 2023, up from 34 the prior year, according to the Community Security Trust (CST), the UK charity that represents the Jewish community on matters of antisemitism and security. (The CST recorded 4,103 antisemitic incidents across the UK in 2023 in comparison.) Yet local leaders do not appear overly concerned about safety.

“Scotland has always been a welcoming place,” said Vicci Stein, who with her husband, Sammy, runs a weekly pro-Israel stand in downtown Glasgow. Unlike in cities like London, “There really isn’t a huge amount of overt antisemitism.”

“We work very closely with the police here,” said Michael Goodman, the president and building manager of the Giffnock Newton Mearns Synagogue in Glasgow. Scotland’s largest shul, it has a minyan three times a day and some 130-140 people each Shabbat, he said.

In fact, Scottish universities granted admission to Jewish students long before their counterparts in England, which required students to take an oath to Christianity as recently as the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Tobias said. In 1779, Joseph Hart Myers, from the U.S., was the first Jew to study medicine in Scotland, graduating from Edinburgh University. Louis Ashenheim from Edinburgh was the first Scottish-born Jew to study medicine, graduating from the University of St. Andrews in 1839.

In Scotland’s capital, Edinburgh, the first Jewish community was founded in 1816, with the first cemetery opening in 1820 and synagogue in 1825. The present Edinburgh Hebrew Congregation, the only “purpose-built” synagogue still used in the city, was built under the auspices of Rabbi Dr. Salis Daiches, who served between 1918 and 1945 and acted as a community spokesman between the world wars. “Because of him the Jewish community has always been held in very high esteem,” said EHC board of trustees representative Dr. David Grant.

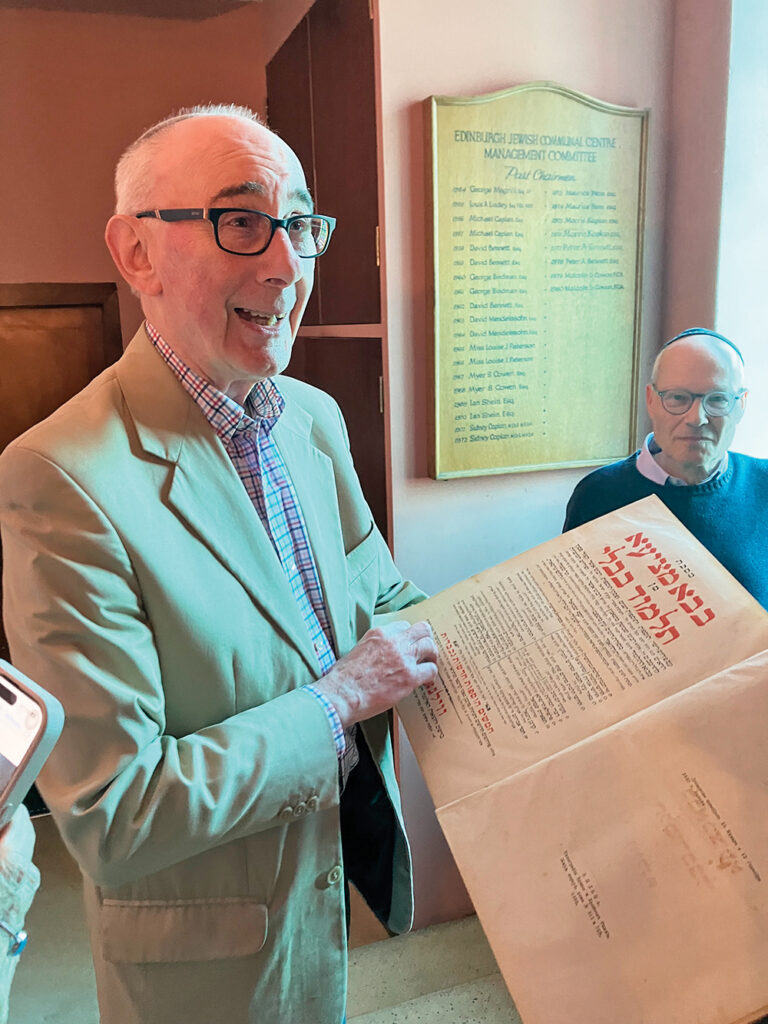

With a membership of some 120 members, an active cheder and 70-80 attendees on Shabbat in the summer, “I’d like to say we punch above our weight,” Grant said. On a recent Sunday visit in May, the synagogue was active with a bar mitzvah celebration being set up and religious school students engaged in activities with young adult mentors. There was also a poster of Israeli hostage Shlomi Ziv, whom the synagogue had adopted. Only a few weeks later, members were elated to find out that he was rescued by the IDF in a daring raid; the shul has now adopted Avinatan Or, the partner of Noa Argamani, who was freed in the same raid. Edinburgh also has a Chabad center and a Liberal (Reform) congregation.

The Jewish population has also undergone a form of revitalization with a growing number of Jewish students studying in Scottish universities and colleges. This young community has received a boost from the appointment of Israeli shlichim who serve as campus chaplains. “The number of Jewish students on Scottish campuses has been growing over the past few years, and we estimate it to be around 600-700 now,” said Rabbi Eliran Shabo, who along with his wife, Ayalah, is employed by the University Jewish Chaplaincy, which supports Jewish students all over the UK. Activities include Friday night dinners, weekly bagel lunches in Edinburgh with 70-80 students, and holiday meals and events—including a Purim Megillah reading and seuda held this year on a boat.

Indeed, while the atmosphere is far from being pro-Israel in Edinburgh—this reporter stumbled upon a pro-Palestinian encampment while strolling through Edinburgh University—there is reason for optimism. While walking to Chabad on a Friday night alongside two kippah-wearing men the same weekend, I was astounded to hear two passersby call out to us, “Stay strong.”

Noting the commonalities between Jews and Scots—who, following a large economic migration of their own in the 19th century, have been scattered around the world—Grant said, “The Scots understand what it is to be uprooted from your home and go somewhere else.”

Lori Silberman Brauner is a communications associate at SINAI Schools and former deputy managing editor for the New Jersey Jewish News. A lover of travel and exploring Jewish Diaspora communities, she is hoping to turn her experiences into a book in the not-so-distant future. Her visit to Scotland was sponsored by Kosher Scotland (kosherscotland.com).