As we confront the latest wave of antisemitism and the war in Israel, we can look to “Shirat haYam,”or Song of the Sea, for inspiration. Drawn from the Torah portion Parshat B’Shalach, it provides us with the opportunity to reflect upon the meaning of song and its impact on our lives during times of great adversity. Moreover, the importance of song in our liturgy is captured in the name given to the Shabbat each year when we read this parashah: the Sabbath of Song (“Shabbat Shira”).

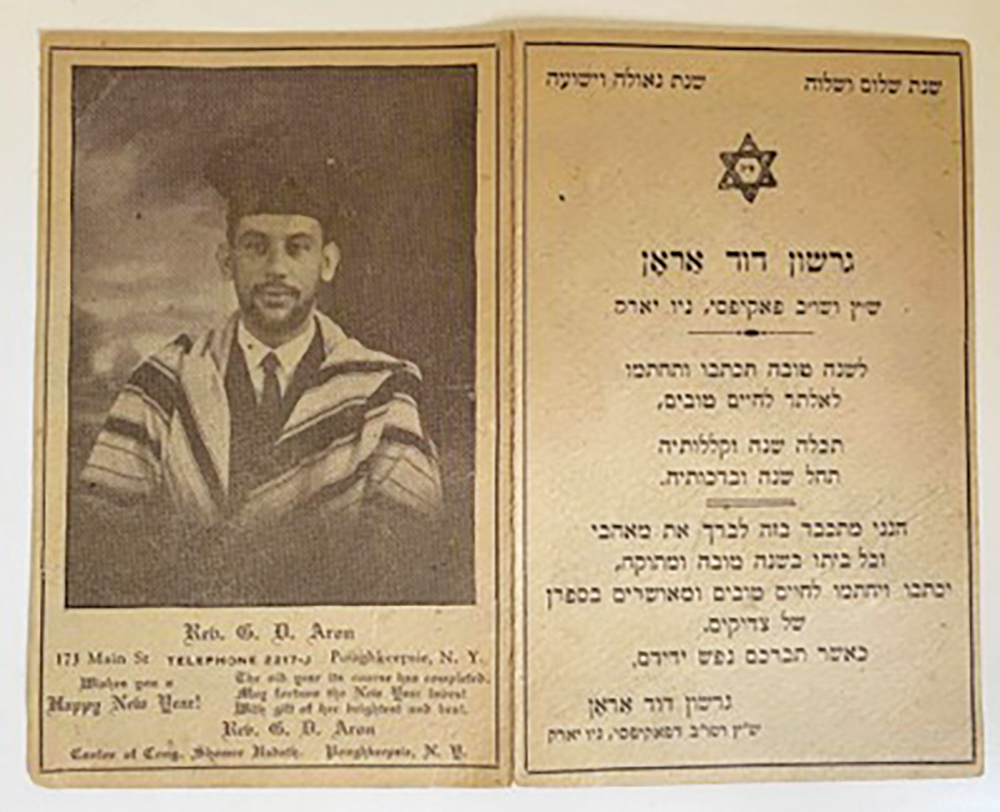

My grandfather established our family’s musical legacy approximately one hundred years ago. Although he received ordination as a rabbi in Europe, in America he supported his family during the Great Depression primarily as a cantor. Both of my parents shared a lifelong love of music. My father and aunt sang Yiddish songs on the radio in Boston as children; my mother played piano and required each of her children to learn this instrument. I was drawn to singing Jewish choral music in the Zamir Chorale in New York under the direction of Maestro Matthew Lazar.

To be sure, singing is also one of the great legacies of the Jewish people. When Moses chose to lead the Children of Israel in song at the Red Sea, it was not only a musical testament of faith, but also a message for all generations. Through this medium, Moses was one of the first conductors of choral music in recorded history. Moreover, the Levites who sang in the Holy Temple in Jerusalem helped create the foundation for the development of Western music. In fact, musicologists have recognized that the styles of musical expression derived from Temple worship were adopted by non-Jews over the centuries. Psalms were sung in alternation between a leader and the congregation in a style that became known as responsorial psalmody.

Elie Wiesel, z”l, a Nobel Laureate and extraordinary humanitarian had a lifelong love of music and singing that was not well known outside the Jewish community. In fact, he was also a conductor of choral music after World War II. At the bar mitzvah of his son, Elisha, he recalled a haunting melody to Ani Mamin from before the war that he taught to a number of us from Zamir who sang for the event. Maestro Lazar arranged the melody for the choir. Our family has been singing the melody at our Seders every year. In his book “Witness,” Ariel Burger described the December 2010 concert at the 92nd Street Y where Wiesel sang melodies from his childhood with orchestra and choir. These musical treasures carry the traditions from centuries of Jewish life that Wiesel cherished and wished to pass on.

R. Gershon David Aron.

During the summer of 1973, Naomi Shemer, z”l, composed a Hebrew version of Paul McCartney’s “Let it Be.” Shortly thereafter, the Yom Kippur War erupted. Her husband Mordechai, on a reprieve from fighting, protested that the moment was too important for her music to be set to Beatles lyrics. She adjusted her composition accordingly, rewriting the song that became known as Lu Yehi, one of her most impactful songs. In Hebrew, the phrase “let it be” translates into “if only” or “let there be,” transforming the melodic message into a prayer for peace. “Lu Yehi” became known as the unofficial anthem of the Yom Kippur War, as Shemer united Jews through music with their history and love of the land of Israel.

Throughout history we have looked to song to bring us together, soothe our pain and rejoice in our victories. Maestro Leonard Bernstein famously noted “This will be our reply to violence: to make music more intensely, more beautifully, more devotedly than ever before…” May we all gain strength from our collective voices and learn to find unity as we yet again face those who seek to destroy us. We need no miracles to accomplish this feat. Just sing a few verses of Shirat HaYam and your friends will surely join along.

Martin W. Aron is a past president and current board member of the Zamir Choral Foundation. He is also a Principal at Jackson Lewis P.C. a national workplace law firm.