Some alphanumeric sequences stay with you as you age, like your first phone number or your college dorm address. It’s 26 years later, and I can still recall my grandfather’s address without trying. His condo was the corner unit on the ground floor at 1395 North East 167th Street in North Miami Beach.

The condo was so small that a step to the left and you were in the kitchen. A step to the right, and you were in the living room.

The kitchen was smaller than I remembered it, but memories like that occur anytime you return to your youth.

You are so much larger than your childhood self, even if your memories are bigger than the shoes they fill.

I stared at the kitchen window. Maybe more than anything about the condo, I always remembered the strange glass of what I called “Florida condo windows.” My mom always called these “louver windows.” These were slatted glass panels with a crank handle to rotate them to the open position like the flaps on an airplane.

Apparently, the word “louver” actually means “slats,” and has the same derivation as the famous museum in Paris. Some call these “jalousie windows,” since the design is supposed to let us see out while no one can see in, which makes the nosy neighbors jealous. In actuality, “jalousie” comes from the Italian word “geloso,” which means “jealous” as well as “screen.”

Yet these windows were invented in Massachusetts in the 1900s, which just drove home the whole absurdity of it all. Nothing about that experience was really native to Florida. Not the fixtures, not my grandparents, not the furniture they brought with them when they left Brooklyn in 1968.

I rummaged through the furniture draws (with permission) while my grandfather watched from the dining room … three feet away. I wasn’t sure what I was looking for. I opened the bureau draws, and the smell of wood was released into the air.

Not the old, musty smell of forgotten times, of organic materials left to rot. This was the aroma of memories. The smell of pipe tobacco or of fall leaves, browned and aged.

I found a picture of my grandfather with a full head of black hair. All I could think is that someone had used Adobe Photoshop to enhance a modern picture.

I forgot that he had once been my dad’s age … or even my own age. To me, he was timelessly frozen like a little old man with steel-blue eyes.

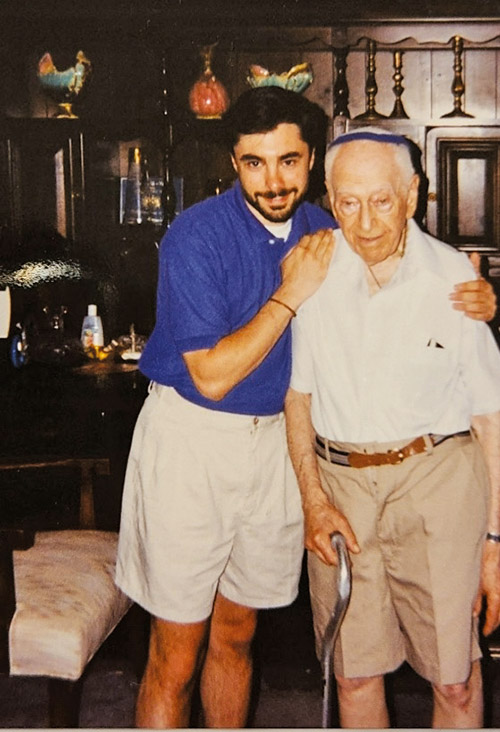

I handed a stack of pictures to my grandfather. The old photographs, flat and two-dimensional in my hand, came to life in his. The past was now here with us in the present as he spoke.

I learned that my grandfather’s mother as a teenager had lugged blocks of ice up flights of stairs to make money. These were the days before electric appliances, before Otis electric elevators. I held the photograph in my hand. I tried to picture my elderly great-grandmother as a teenager, carrying a 10-pound block of ice.

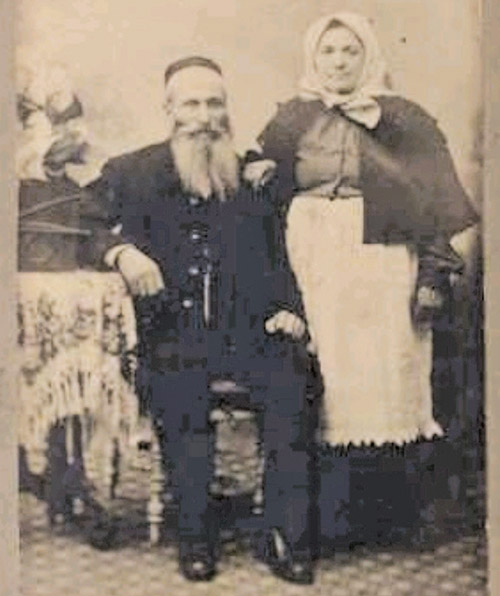

Another picture stood out—a husband and wife. He was sitting, she was standing, but she was so short, he was almost taller than her while sitting.

I was looking at my grandfather’s mother’s parents. My grandfather’s grandparents. I let that sink in. If grandfather had been born in 1902 and his mom was born in 1870, his grandparents might have been born in 1850. This is before Abraham Lincoln ever ran for political office. A time before electric lights, automobiles or even telephones.

Did he have any of his grandparents’ documents?

“No … but the candlesticks were my grandmother’s.”

What candlesticks?

“Those over there on top of the bureau.”

I was 27; I had been to the condo every Chanukah between 1968 and 1980, but I had never noticed them. Had they always been there? It’s funny how many things are in our sight, but we fail to see them.

If anthropomorphism is the sin of giving life to that which should not be birthed, then I am guilty of a thousand life sentences. I had embraced my grandfather’s pinky ring, his father’s pocket watch, and now his grandmother’s Shabbat candlesticks.

He did not know how a teenage girl from Eastern Europe came to own these brass Shabbat candlesticks or when the candlesticks came to America. It was just one piece of those legends that were part of my family’s “unicorns.”

After three days of listening, and recording those unicorns, it was time for me to go home.

If I close my eyes, I can still see him standing there waving me goodbye as my cab pulled away. The palm trees, still in the humid Florida summer air. I don’t know if he knew that this was to be our last meeting. Had he told me everything I needed to know, or we’re there more unicorns to share?

It wasn’t until I spoke to my parents on my return home that I understood that the unicorn I was looking for wasn’t really the photographs or the candlesticks. You can’t know where you are going if you don’t know where you came from.

I had come looking for my grandfather to tell who we were as a family—and as the only son of the only son, where I was going.

I had planned to return and ask more questions in the fall, but it was not to be.

Shortly after my return home, we learned that my grandfather collapsed. My father had him flown up to New York, but my grandfather never regained consciousness.

For six weeks I went to the nursing home to watch him sleep. I spoke with him, and I believe that he heard me, but he had nothing more to tell me. Like the unicorns, he, too, was frozen in time.

David Roher is a USAT certified triathlon and marathon coach. He is a multi-Ironman finisher and veteran special education teacher. He is on Instagram @David Roher140.6. He can be reached at [email protected]