Dr. Gerald (Jerry) Berkowitz, raised in Philadelphia, married Rivke Klein, the daughter of a prominent Buffalo rabbi, in 1965. Her condition? That he would be willing to make aliyah. Sadly, their dream was not to be.

After receiving his doctorate in chemistry, Jerry, along with Rivke and their 2-year-old daughter, Talia, flew to Israel for the summer of 1970 to see what it was like to “live like Israelis rather than tourists.” Albeit somewhat apprehensive about flying after a rash of recent hijackings, their trip was successful, and they boarded their return flight carrying lots of mementos.

That fateful flight left at 6 a.m. on September 6. It was Elul, and the young family, with another baby on the way, was scheduled to be back in New York for the yamim noraim. After a stopover in Germany, they were settling back in for the last leg of the trip when members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestinian (PFLP) stormed the plane and reversed its course, flying to Amman, Jordan.

Rivke and their daughter were held captive on the plane for a week, along with 40 children and nine babies in diapers, all because they were Jewish. With barely any food, no air conditioning in the sweltering daytime weather nor heat in the cold desert nights, and horrible bathroom conditions, Rivke, a teacher, managed to entertain all the children. The pilot and crew were also taken captive. Rivke not only lost 10 pounds that week but later learned she had been carrying twins and one had not survived.

Dr. Berkowitz was the first of six men taken off the TWA plane and held hostage in retaliation for detained Palestinians, including convicted murderer Sirhan Sirhan, arrested for the assassination of Senator Robert F. Kennedy in 1968. Two others taken with him were rabbis with Israeli-American passports, and three non-Jewish U.S. government officials. Driven to a remote location near Syria, no one knew where they were.

Berkowitz’s description of the weeks that ensued is rife with horror, but he relates that they were not injured and, “B”H, the captors were Marxists and not Islamic terrorists.” Still, he survived being locked in a small room with one cup, a pitcher of water, a small table and two chairs for the six men. They needed permission to use a hole outside for a toilet, and had no showers nor were they able to brush their teeth. Their meals consisted of “pita, hard-boiled eggs and some jelly for the three Jews. The others had a few good meals and were given shepherd’s pie.”

Berkowitz, 31 at the time, never let his captors know he spoke Hebrew or that his parents were born in Palestine. His parents, he noted, “were deathly afraid that it would become known that they were born in Palestine, which would lead the PFLP to conclude that I was Israeli, which would not be a good thing. They would not talk to the press at all. They basically became hostages in their apartment.”

Since the goal of the captors was to hold the men hostage in exchange for Arab prisoners, Berkowitz said he never asked, “Why me?” but rather, “Why not me?”

Allowed a radio on and off throughout the three-plus weeks in captivity, he laughed at the memory of hearing President Nixon announce, “Glad everyone has been released,” and “It’s more intense when you’re not there.”

Berkowitz commented, “A very difficult situation for those not on the plane was dealing with false information; it was harder for those at home in the days before around-the-clock news coverage.” He said that his father-in-law was unable to conduct Selichot services and his brother-in-law, a manager at IBM, would be at meetings and every hour on the hour turn on the radio for updates.

While in captivity, Dr. Berkowitz woke one morning to learn that war had broken out between the Jordanians and the Palestinians. Pictures in the Arabic newspapers showed the planes had been blown up. The men were then told they were no longer hostages but prisoners of war. On September 29, Berkowitz and the other captives were turned over to the Red Cross.

Upon release, he was given the option to fly to Israel, Greece or the States. Having heard that the plane was blown up with those on board and not knowing if his wife and child were alive, he chose New York. His wife, having arrived home on September 14 to the fanfare of 250 people waiting, did not know if her husband was alive. She refused to listen to the news, as there were too many instances of non-facts being relayed.

Berkowitz arrived in New York on Erev Rosh Hashanah with the Middle East Airlines Red Cross crew. He was 25 pounds lighter and sported only the clothes on his back. There was no fanfare; only his brother-in-law, wife, daughter and a police escort were there to race him back home in time for sundown; he chuckled, “No time to shower.” The family was in White Plains for Rosh Hashanah and Buffalo for Yom Kippur, where his father-in-law was a pulpit rabbi.

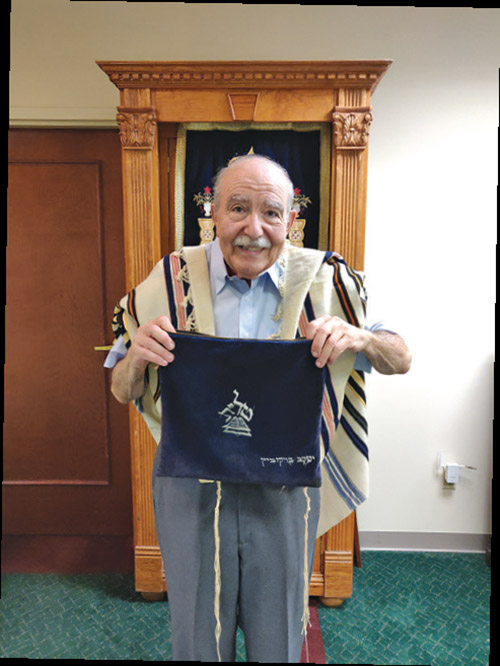

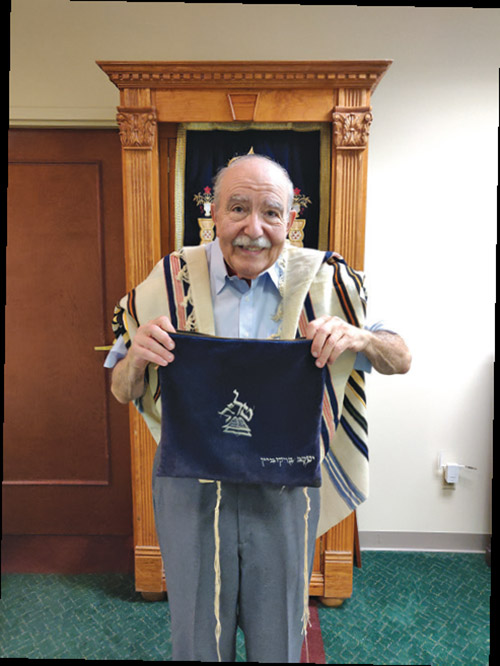

Not only did the captors take the Israeli items out of their luggage, in Berkowitz’s case they also took his doctoral dissertation—which he said, laughing, he had brought in case he found a job—and his tallit. His wife had instinctively taken the prayer shawl out of their hands while demanding, “You can’t have that. You took my husband, and you can’t have this too.” He acknowledged triumphantly that he wears it to this day.

As for the jewelry they purchased while in Israel, which was stolen and left at the front of the aircraft, his wife threw her hat over it, swept it into her hand and stole it back. Talia was not told about the souvenirs from the trip until she was 16 and about to return to Israel for the first time. She was the first of the family to go back, to attend a conference representing Buffalo teens. Dr. Berkowitz said they “decided we could not let our reticence affect our kids.”

Being part of the last major hijacking when everyone lived, they never outlived the nightmares and flashbacks. Their losses were immense, and while they may have been released from captivity, Berkowitz revealed that his wife was never “released.”

Rather than board a plane to make aliyah, in 1971 the Berkowitz family traversed the roads from their home in White Plains to Buffalo, where they settled. Dr. Berkowitz had a part-time position as principal of the high school of Jewish studies there, and Rivke was a Jewish educator and associate headmaster at the school her parents co-founded, Kadimah Day School of Buffalo, now Kadimah Academy, where Talia Berkowitz taught until its closing. Today she teaches at the Chabad school. Rivke and Jerry devoted untold volunteer hours as National Conference of Synagogue Youth (NCSY) advisors and were voted as Advisors of the Millennium for Upstate.

Rabbi Ethan Katz of Fair Lawn tells his NCSY members that his Aunt Rivke and Uncle Jerry Berkowitz are “the greatest heroes.” “They stood up to the terrorists without fear and fought them every step of the way. Then they dedicated their lives to teaching that education is the Jewish answer to terrorism. What they have done is taken this tragic experience and used it to impact the Jewish future. This is how we thrive and not just survive.”

From the late 1980s, Rivke and Jerry saw to it that their four children took turns traveling to Israel. They wanted them to love Israel despite what happened to them. Their son Boaz realized their dream and made aliyah, settling in Modiin. Their daughters Yael Rosenberg from White Plains, Leora Sulimanoff from Teaneck and Talia from Buffalo are all proud Zionists.

Berkowitz feels blessed to have his family. He recalls that while in captivity, he looked up to the sky on the last Saturday before Rosh Hashanah and “a quote from Genesis came to mind. ‘God told Abraham to look at the sky and promised to make his descendants as numerous as the stars in the heavens.’”

Rosenberg and Sulimanoff took upon themselves a letter writing campaign to rebuke the planned speaking engagement of Arab terrorist and convicted hijacker Leila Khaled. A teacher at Yeshivat Noam, where her son learns Torah with the grandson of David Raab, another hijacking survivor, Sulimanoff explained that Khaled, a thwarted hijacker on an El Al plane, one of four planes hijacked the same day as the plane carrying her parents, “was arrested and later released as part of a deal of releasing hostages.”

Because of their experiences, it took many years for Rivke and Jerry to be able to travel by plane, making only about 10 airline trips in 50 years. Berkowitz remarked, “If we couldn’t drive, we didn’t go.” The first time he returned to Israel was when he was invited to speak at a conference 18 years after being held captive; his wife would not go. She flew there the following year with her mother and aunt. Returning a few times since, mainly for the births of their grandchildren, he said they did not make regular trips to visit; it was never easy for Rivke to step on a plane.

Berkowitz recalled with breathtaking imagery the times his wife, who passed away in 2015, needed to fly, noting that she shook so much her body was vibrating at the airport before boarding, causing someone to run over to offer her oxygen. Each trip they took, he remarked, “took a tremendous toll on our lives.”

Sadly, he said, “a lot has not changed. From 1970 to 9/11 we didn’t learn anything as a country about how easily another plane could be taken. A lot of politicians are stuck in the past in 1948.”

Berkowitz’ religious beliefs remain firm. He practices as faithfully as he did before the events that changed the trajectory of his life. He fervently recalls that each night throughout his captivity, he said a prayer. Fifty years later, he is devoted to Jewish education and Jewish community work. Their first born grandson is a freshman at Frisch. As a sign that their hearts forever remained connected to Israel, the Berkowitzes are referred to as Abba and Ema by their children.

By Sharon Mark Cohen

�