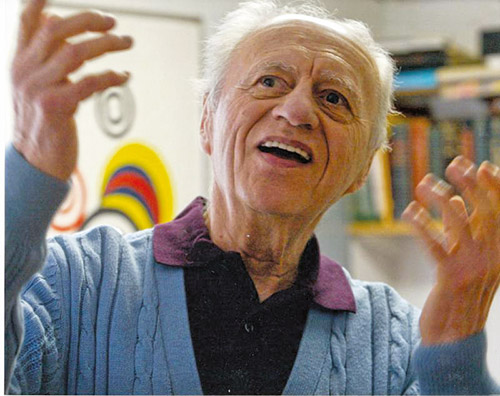

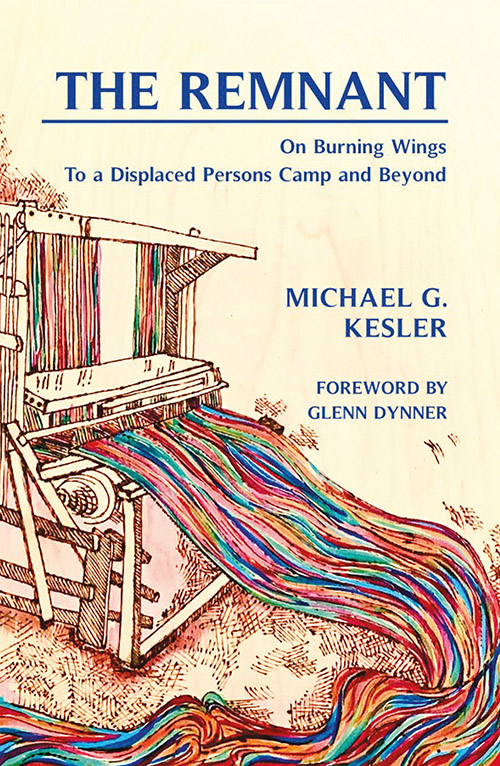

Highlighting: “The Remnant: On Burning Wings—To a Displaced Persons Camp and Beyond,” Michael G. Kesler. Vallentine Mitchell & Co Ltd. Paperback. 168 pages. 2021. ISBN-10: 191267663X.

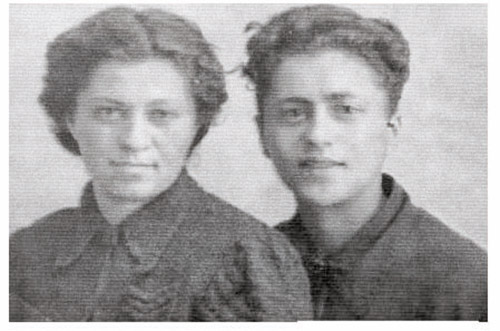

“I know of Hitler’s hatred of the Jews. But what good will it do for him to kill innocent civilians? How many Jews can Hitler kill, after all? A thousand, two thousand?” Those chilling words by their mother gave Meesha (aka Mekhel or Michael) Kesler and his sister Luba an unsettling send-off in June 1941. Their mother stayed back and was killed along with their father and other family members. “The Remnant: On Burning Wings,” the latest work by Michael G. Kesler, tells the story of the teenage siblings who left their family and fled their homeland of Dubno, Poland as war raged.

In 1931, Dubno, which Kesler describes as “a Jewish, historic town,” had a population totaling 12,696 with 7,364 Jews. After the war, only about 300 Dubno Jews were alive. Of the inhabitants, 59% were killed in the Holocaust. Now part of Ukraine, Dubno has no Jewish community.

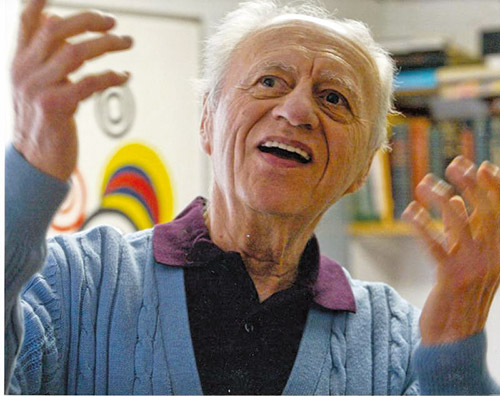

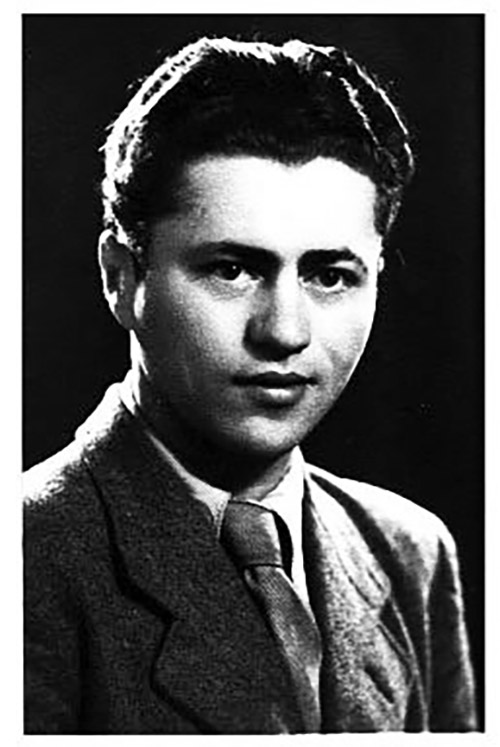

Kesler, born June 22, 1924, holds a doctorate in chemical engineering. With degrees from MIT and NYU, he enjoyed a high-powered career in the petroleum industry for more than 50 years, retiring in 2006. He shares his easy-to-read, hard-to-take story of his four years in exile and beyond in his newest book.

In 1937, Kesler transferred to a Hebrew school because of rising antisemitism in the public schools, he explained. When he became a bar mitzvah, he was away from home studying in the Tarbut Gymnasium in Ostrog, Poland.

Later, while living in a Soviet occupation zone, Kesler was drafted into the Red Army. At his sister’s urging, the teen deserted, a crime punishable by death. With forged papers, a new name and birthdate, he struggled with shame and guilt as the two made their way to Samarkand, Uzbekistan.

Kesler and his sister walked thousands of steps and mastered hopping many moving trains before setting up a home in Uzbekistan. While there, the young entrepreneurs started a business with Kesler weaving and Luba, with her outgoing personality, selling his wares. In the evenings, Kessler studied economics.

After the war, Kesler, torn by a platonic relationship with a townswoman, wrote, “But I am not an Uzbek. Then another thought occurred to me: Nor am I Jewish! During four years of exile, Luba and I had never celebrated the Sabbath or any other Jewish holiday. The torrent of conflicts began to tear me apart. I felt myself floating in mid-air without mooring.”

Kesler and his sister, three years his senior, found their way “home” to Dubno after the war to be met by a mass grave of all the Dubno Jews, including their parents. “Jewish survivors, uniquely, soon found there were no relatives and no homes to return to. Further, they feared that returning to their homes would provoke Jewish killings of the kind that had taken place in Kielce in July of 1945.”

They quickly escaped to the next phase of life in a displaced persons (DP) camp in Germany on December 24, 1945, by traversing Poland and Czechoslovakia. Kessler was “overcome by the guilt of having lived through the slaughter,” yet he “accepted it as a necessary burden.”

From the DP camp, Kesler’s destiny took him from Paris to the States. Luba, her husband, Moniek, a Bobover Chasid follower, and their infant son received sponsorship by an aunt to live in Uruguay.

After a year in Uruguay and two in Argentina, Luba, Moniek, their son, and new baby daughter immigrated to New York. In 2012, at the age of 90, Luba passed away. Moniek succumbed in 2016 at 96. They had nearly 50 descendants at their passing, including, as Kesler added, “three dozen great-grandchildren, now approaching marriageable age—in the setting of Orthodox communities where people marry young and raise large families.”

As for Kesler, when Hillel awarded him a scholarship to Colby College in Maine in 1947, it came with the condition that he first live in France for at least six months. That was a requirement to establish legal residency before moving to the States as “the American consulates in Germany stopped accepting applications for visas from Jews.”

Passover in Paris, Kesler explained, “fell in mid-April that year, and the Seder was conducted in the cafeteria by a young rabbi who spoke French. It sounded strange to me, although I had become comfortable with the language and knew most of the melodies and sang them with gusto. The joint provided the kosher meal.”

The next day, Kesler and his friend entered the famed Rothschild synagogue and joined services. “The cantor, a well-trained tenor, and the male choir sang the Prayer for Dew, composed by Yossele Rosenblatt, which I knew well. The prayer was so moving that I felt as if transported to the Great Synagogue of Dubno, where I had sung as a soprano in Cantor Sherman’s choir.”

Kesler went on, “I had not been to a synagogue, nor heard a cantor and choir, since leaving home nearly six years before. It was as though part of me had returned home after a long absence.”

After making his way to the States, Kesler started at Colby, later transferring to MIT in the fall of 1948. Kesler wrote that one of his professors at MIT was “Professor Edward R. Gilliland, co-inventor of the technology that processes crude oil for gasoline production, which had become essential for winning the war against Hitler.”

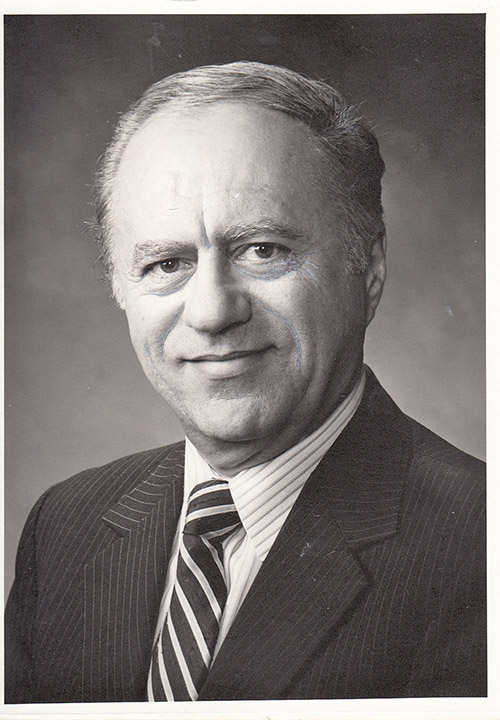

Kesler met his first wife, Regina Chanowicz, a Harvard-trained pediatrician with a similar survivor’s background, in the summer of 1951. They married in the winter of 1952. Their careers were flourishing when, tragically, Regina died after a battle with breast cancer, and Kesler was left to raise their four young children, ranging in ages from 12-20. During those years, he was the cantor at the Jewish Community Center of Paramus (JCCP).

Once again, Kesler found his way, marrying Barbara Reed, Ph.D., in 1985. The journalism professor and mother of two teenagers is the niece of Dr. Abraham Joshua Heschel. Kesler declared, “Barbara opened my eyes to a broader, deeper and more nuanced view of Judaism and its relation to other faiths.” Together they married off their six children to Jewish spouses and now head a family with 11 grandchildren.

The true dichotomy of the man can be applauded as Kesler went from survival mode to living a Jewish life of prosperity. He has resided in East Brunswick for over four decades. Dr. Kesler, at 97, a member of two synagogues, feels “proud, yet humble, to carry on [his] forbears’ legacy.”

Writing books, sponsoring concerts and lectures, and performing timeless Yiddish songs, make Kesler happy. “The desire to pass along to my progeny, friends and others the details of my harrowing past,” he added, comes from “my origins as a Jew.” Kesler, a remnant extraordinaire, concluded, “I had an epiphany: The Jews had been born to inform.”

By Sharon Mark Cohen