A brayta on Sukkah 53a relates that Rabban Shimon b. Gamliel I would rejoice at the Simchat Beit HaShoeva, the ceremony of Drawing of the Water for the altar, by juggling eight flaming torches. A second-generation Tanna, he lived 10 BCE to 70 CE, during Temple times. (The later Rabban Shimon b. Gamliel, a fifth-generation Tanna, was but a youth during the Bar Kochba revolt, and so this isn’t him.) The Talmud then relates the juggling actions of various Amoraim well after the Temple’s destruction. Though nowadays we celebrate a “Simchat Beit HaShoeva,” this doesn’t seem to be the context of the Amoraim’s actions. Levi juggled eight knives before Rebbi (Yehuda HaNasi). Shmuel would juggle eight cups of wine before King Shabur (/Shapur), and Abaye would juggle eight eggs, or perhaps four eggs, before his teacher Rabba. (We must emend the text from Rava, who was his colleague.)

The Gemara refers to more than one King Shabur. King Shapur I reigned from 240-270 CE, while Shmuel lived from 165-257 CE, so this juggling was likely during this 240-257 span, when Shmuel was at least 75 years old. King Shapur II, who reigned from 309-379 CE, is the one who was “friendly” with Rava (280-350 CE). His son, King Shapur III, reigned from 383-388 CE, and is not referred to in the Talmud, not even by Rav Pappa (d. 375 CE). The name is derived from Old Iranian xšayaθiya.puθra, “son of a king,” so might originally have been a title.

We thus see that Shmuel was on friendly terms with King Shapur I and accorded him honor. In Bava Batra 54a / 55b, Abaye and Rabba each report that Shmuel maintains דִּינָא דְמַלְכוּתָא דִּינָא, the law of the land is the law (and from there to three other times in Talmud). Shapur seems to have generally been friendly to the Jews, and in Moed Katan 26a it is reported that he said to Shmuel, “I have a blessing coming to me, for I have never killed a Jew?” This report is contrasted with the fact that Shmuel was told that King Shapur killed 12,000 Jews in Mezigat Caesarea, and Shmuel didn’t rend his clothing. The Talmud resolves it, stating that King Shapur never instigated the killing but these residents had rebelled against him.

Possibly it was due to this friendship that Shmuel himself was called King Shapur, but I don’t find this interpretation compelling. Specifically, in Pesachim 54a there is a Biblical interpretation by Rabban Yochanan b. Zakkai that, in the genealogical account in Bereishit 36, Anah of verse 20 is the same Anah as in verse 24, even though the first verse has Anah as Tzivon’s brother and the latter as his son. The implication is that incest was at play. As support for this folding of Biblical personalities, we see a drasha from an Amora:

וְדִילְמָא תְּרֵי עֲנָה הֲווֹ?! אָמַר רָבָא: אָמֵינָא מִילְּתָא דְּשַׁבּוּר מַלְכָּא לָא אַמְרַהּ, וּמַנּוּ? שְׁמוּאֵל. אִיכָּא דְּאָמְרִי: אָמַר רַב פָּפָּא: אָמֵינָא מִילְּתָא דְּשַׁבּוּר מַלְכָּא לָא אַמְרַהּ, וּמַנּוּ? רָבָא; אָמַר קְרָא: ״הוּא עֲנָה״ — הוּא עֲנָה דְּמֵעִיקָּרָא.

Thus, “he is Anah” in the latter verse implies that he is the same Anah as before. In the first version of this statement, it is Rava who says it, introducing the drasha with, “I will tell you something that even King Shapur hasn’t said.” The Gemara interjects that King Shapur obviously isn’t the Persian king, but refers to Shmuel. Presumably this is because King Shapur was not Jewish and didn’t interpret Biblical texts. In the second version of the statement, it is Rav Pappa who makes the statement, and by King Shapur, he means his primary teacher, Rava. (In the parallel sugya in Bava Batra 115b, Rabba is substituted for Rava in both the first and second versions, but Rava makes more sense. See the interactions between Rava and Shapur II / his household in Taanit 24b and Chagiga 5b.)

Rashi explains that Rava called Shmuel this name because Shmuel was an expert in financial law (dinim) and the halacha is like him in such laws, like the laws that are established when uttered by the king. He adds that Shapur of the Persian kings was in Rava’s days.

It seems odd that Rava, a fourth-generation Amora who was close to King Shapur II, would refer to Shmuel, a first-generation Amora who was close to King Shapur I, by the name “King Shapur.” As a sign of respect (as per Rashi), it makes more sense than if it were a joking reference to their friendliness. Still, would Rava, who had to worry about (Taanit) execution by and (Chagiga) bribing of King Shapur II, risk referring to another Amora by this name and title, at the same time that Shmuel knew Shapur I and he knew Shapur II? Also, Shmuel’s expertise in financial law has no bearing on interpreting genealogical verses. There is nothing to connect Shmuel to the content of the drasha.

I would suggest that Rava indeed intended King Shapur II, who waged two wars against the Romans and persecuted Christians under his rule after Constantine declared Christianity the religion of the Roman Empire. Chazal equated Edom with Rome and eventually Christianity. Rava is saying that even King Shapur, who hates Rome, didn’t say this drasha that impugns their lineage.

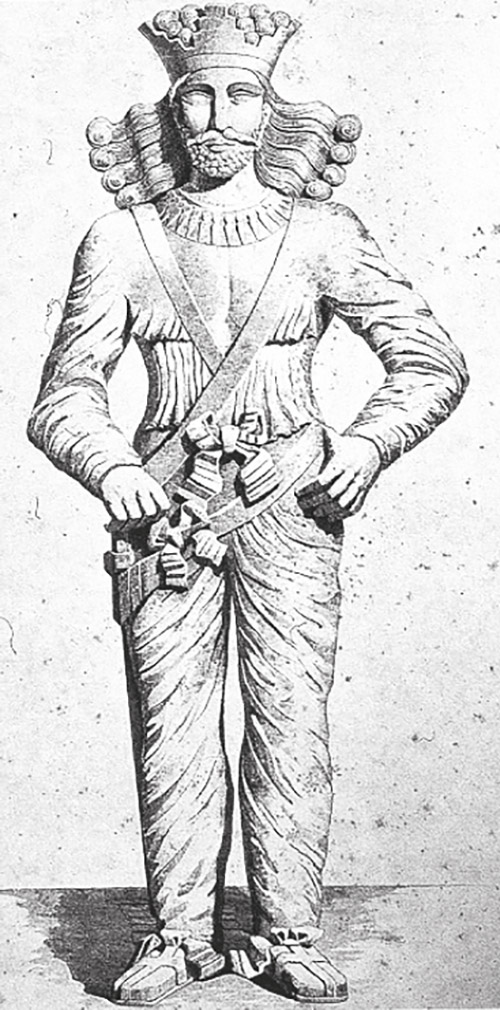

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman’s colleagues don’t refer to him as King Shapur, but he nonetheless switched his profile to that of King Shapur I to see if the appellation catches on.