On August 24, various BBC broadcasts heralded the launch of the 2021 Tokyo Paralympics.

Ironically, they neglected to mention how the Paralympics were shaped by Sir Ludwig Guttmann, a refugee to England, a spinal injuries specialist and the competition’s beloved founder. Ironically, because as mentor and mascot to scores of paraplegic men and women, he left an indelible imprint on their lives, restored their dignity, and brought the games international prestige. Ironically, because the BBC has, at other times, recognized the competition’s founder in news, documentary and fictional formats, such as “The Best of Men” (2012, see below). Despite this, relatively few people comprehend how a refugee from Hitler upended the mortality rate for downed, paralyzed RAF airmen and others with paraplegics, and restored them to the fullest lives possible. Dr. Guttmann, affectionately called “Poppa” by those whose lives he championed, and afterwards lauded as Sir Ludwig Guttmann, did just that.

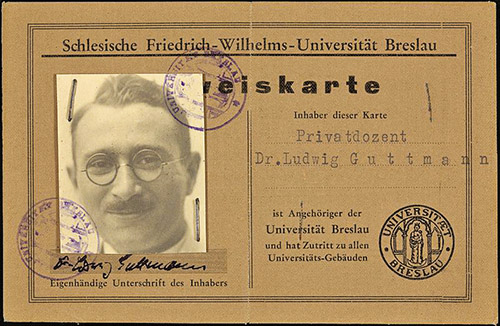

Often in life, what at the outset seems a curse or reversal of fortune turns out to be a blessing, not just for those affected by the “setback,” but for those around them, and for society at large. Such was the case when Guttmann, a highly respected neurologist in Breslau, Germany, was forced to flee to England with his wife and children, just prior to the start of World War II. As a result of the infamous 1933 Nuremberg Laws, Guttmann was ousted from his decade-long position in the Department of Neurology and Neurosurgery at the hospital in Breslau, and he transferred to the Jewish Hospital of Breslau. There, on Kristallnacht, he ordered his staff to honor any patient’s request for admission and covertly “coached” 60 Jews in how to feign illness convincingly enough to escape the Gestapo’s clutches and deportation to concentration camps.

Guttmann was subsequently summoned to Portugal at the request of the dictator Antonio de Oliveira Salazar, its prime minister, to treat a patient there. During this visit he learned that the English Society for the Protection of Science and Learning had secured visas to England for him and his family. His initial four years at Oxford’s Radcliffe Infirmary was by all accounts a coveted appointment, and so his fellow physicians were perplexed when he decided that his medical skills could be better applied elsewhere at Stoke Mandeville Hospital in Buckinghamshire, just over an hour and a half from central London (Akkermans, 2016, [The Lancet Neurology]).

Stoke Mandeville Hospital for Spinal Injuries was a work environment hostile to the kind of innovation that Guttmann pioneered, and when he joined the staff, the maximum life expectancy of paraplegics was two years. His recommendations that patients be turned in their beds every two hours to avoid bedsores and infections leading to amputation, and that sedation be reduced, rather than maintained (ostensibly to keep patients docile) were met with steep resistance from other physicians. Sedated patients were much more manageable, and in his Stoke Mandeville colleagues’ minds, paraplegics’ lives held little value, with minimal, if any, expectation of productivity. So, they reasoned, why bother to focus on training them?

In the hospital’s hierarchy, less skilled doctors with authority over him dogmatically rejected his life-prolonging measures. Eventually, though, even those who scorned him could not deny those measures’ empirical success, nor weaken Guttmann’s empathy and conviction that despite their paralysis, these men and women could recover, be reunited with their families and contribute to society.

In contrast to his Stoke Mandeville peers, Guttmann challenged patients to develop muscular strength first through archery, and then via basketball. He hired a trainer from the Royal Armed Forces and other therapists to focus on patients’ upper-body workouts and to engage them in games on the hospital grounds. These games spurred patients to compete more fiercely in these sports.

Although Gutmann himself was a strong personality and made sure his patients adhered to a strict physical regimen, they also responded to his gentle and caring side. Hence, he was dubbed “Poppa,” a name that stuck. His determination and commitment to have them leave Stoke Mandeville and go back to their families drove his insistence that his patients persevere. His faith in their abilities catalyzed a change of heart even in those patients most afflicted with depression and a sense of hopelessness.

What began in 1948 as a lawn competition among 16 paraplegics at Stoke Mandeville became, the following year, an inter-hospital competition with 60 participants; by 1951 that number had more than doubled and other sports complemented basketball and archery games. In 1952, on the first day of the London Olympic games, the first International Stoke Mandeville games were held and included paraplegic Dutch war veterans.

Guttmann envisioned that the International Paralympics would eventually “piggyback” on the Olympics themselves, and so, the 1960 Paralympics were held in the Rome Olympic venue (Akkermans, 2016, [The Lancet Neurology]). There were 400 athletes competing in 23 sports (International Paralympics Committee). Currently, 4,403 athletes, including 1,853 women, are competing in 22 sports/23 disciplines in Tokyo (paralympics.org). They come from 162 countries, and “… a delegation of refugees” (nytimes.com) and there are 539 events (en.as.com).

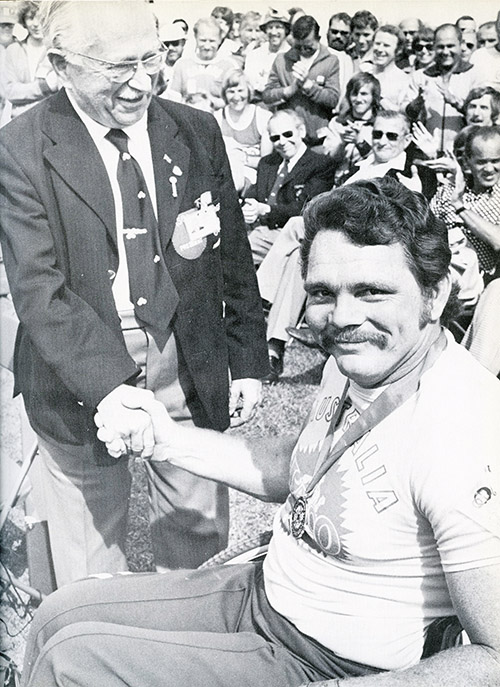

Paralympians from other countries, as well as those who observe them and award them their medals, have recognized that Sir Ludwig Guttmann was ahead of his time. In as much as his treatment of paraplegics emphasized maximizing and recognizing their abilities, as opposed to pitying them because of their disabilities, Guttmann was a visionary and a lone pioneer.

In 2012, concurrent with the London Olympics, BBC Oxford ran a segment on Guttmann and the history of Stoke Mandeville, and interviewed paraplegics who attested to Guttmann’s legacy, his work and his vision for paraplegics that focused on abilities rather than dis-abilities. It is only very recently that media and other representations of disabled persons’ strengths and contributions have been more fully emphasized, and the international community is indebted to this very special refugee. Germany’s loss was the world’s gain.

In tribute to Sir Ludwig Guttmann, founder of the Paralympics, please enjoy the sources below.

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/medal-quest/past-games/

https://www.bbc.com/news/av/uk-england-oxfordshire-19368602

https://www.paralympic.org/ipc/history

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k-rB6QdAa_Y

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-08-24/why-i-love-the-paralympics-kurt-fearnley/100392068

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt2374835/ (The Best of Men)

Rachel Kovacs is an adjunct associate professor of communication at CUNY, a PR professional, theater reviewer for offoffonline.com—and a Judaics teacher. She trained in performance at Brandeis and Manchester Universities, Sharon Playhouse, and the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. She can be reached at mediahappenings@gmail.com.