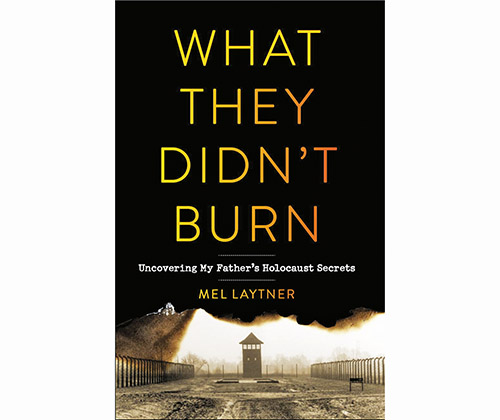

Highlighting: “What They Didn’t Burn” by Mel Laytner. SparkPress. 2021. English. Paperback. 304 pages. ISBN-13: 978-1684631032.

Mel Laytner, formerly a journalist, grew up on West 83rd Street in Manhattan along with many other families of Holocast survivors. Laytner attended local public schools and CCNY for college, and eventually earned graduate degrees from Columbia’s School of Journalism and School of International and Public Affairs. His 20-year career as a journalist was mainly as a foreign correspondent covering the Middle East for NBC News and United Press International.

Growing up, Laytner remembers his father, Joseph, as a quiet, soft-spoken and often passive individual. He read seven daily newspapers from cover to cover. When socializing with other Holocaust survivors, he never drank, nor did he join card games involving gambling.

Although trained as a metal welder in Poland, he did not want to pursue this line of work in America as it would bring back dark memories. He began as a presser at a Ripley’s Clothing store and eventually was persuaded by his wife, Helen, to open a candy store on Broadway. The store was successful for several years but as the neighborhood changed, the Laytner’s traded their candy store for a popular linen shop, and thus entered the world of the middle class.

Laytner recalls many hours sitting beside his father on the green, velvet living room chair and hearing vignettes about his father’s years as a prisoner during the Holocaust. Laytner realized later in life that relying on the memories of his father’s remembered stories would never “pass snuff.” As he expresses in his introduction, “The truth was I had no facts, only memories of facts. I could tell my daughters no more because I knew no more. I had been repeating my father’s vague vignettes in a vacuum.”

Joseph Laytner passed away from a sudden heart attack at age 73, before the birth of his first grandchild. Mel remembers vividly the large funeral at Riverside Memorial Chapel where many unfamiliar faces came to pay their respects. The date was April 21, 1985, exactly 40 years after his father’s liberation from Buchenwald, the last stop on his Holocaust journey. A month later, while sipping coffee in Jerusalem at a cafe overlooking the Western Wall with Walter Spitzer, a noted French artist who had been befriended by Laytner’s father as a teenager in the camps, Laytner learned of another side of his father. When Laytner asked Spitzer how his father had survived, Spitzer responded with a knee-jerk comment that shocked Laytner.”I’ll tell you how. Dolek (nickname for Joseph) was a bastard! A real bastard! You had to be one to survive!.”

It took Laytner 20 years to follow up on this startling revelation. Laytner arranged for his first trip to Poland in 2005, followed by two more trips to Poland, Germany and Israel, in 2007 and 2015. On these trips he followed a paper trail that began in the small Polish village of Dabrowa, where his father had grown up in a wealthy family of metal manufacturers, then on to the small ghetto from which his family was separated, his father being sent to labor camps through the Organization Schmelt where he worked as metal worker producing vital equipment for the Nazis. His father’s longest and most brutal experiences were the 19 months spent in Blechhammer, a sub-camp of Auschwitz, where prisoner workers survived only if they were productive in welding wares for the SS. After Belchammer was bombed in July of 1944, Joseph Laytner was sent to Gross-Grosen where he worked under cruel Ukrainians. He was finally liberated after escaping from a death march from Birkenau, the killing camp of Auschwitz.

Through accessing official Nazi documents stored at government offices, museums, synagogues and memorials in Poland, Germany and Israel, Laytner found out several startling revelations about his father. Short but strong, Joseph Laytner was punished with 25 lashes for trading for food, clothing and other necessities with a store of diamonds he received from a dying Belgian prisoner. He had been involved in a thriving black market not only with fellow prisoners but with SS guards and British prisoners of war. Hiding these diamonds between his toes, he was able to conceal them from the SS guards until they were discovered and he was punished with 25 lashes. The record of these lashings rests in the archives at the Ghetto Fighters Museum in the North of Israel.

Laytner also discovered that although his father was clever and conniving, when he was offered the position of Judenrat, a Jewish prisoner assigned to oversee a barracks, discipline the prisoners and report back to the Camp Commandants, Dolek declined even though it would have meant better daily rations and accommodations. He would not assume a position that would cause more suffering to his fellow prisoners.

“What They Didn’t Burn” is a unique combination of a personal narrative and a historical record. Laytner intersperses very emotional human responses with facts and figures. An example of the latter would be the complicated calculation of how much a forced laborer would cost the German government to maintain yearly as $745. This figure contrasts sharply with Laytner’s very searing comment about how his father viewed survival. “Survival required you to lobotomize your psyche and excise the fellow in the next pallet. Survival was more a game of solitaire than of bridge. House rules were brutal. Winners got to play again tomorrow. Losers did not.” Is it any wonder that Joseph Laytner did not choose to play cards.

By Pearl Markovitz