When many people think of the waves of Jewish immigrants who came to this country around the turn of the last century, peddlers with pushcarts and shop owners crowded into cities are often pictured. However, many eschewed the congestion of city tenements to become farmers, especially in New Jersey, where they lived in colonies that no longer exist.

In fact, the first Jewish farm colony in North America was the Alliance Colony in

Pittsgrove, Salem County, now a national landmark. The community at one time boasted cigar, canning and clothing factories. The community is now undergoing resurrection of sorts through the Alliance Community Reboot, a nonprofit seeking to rebuild the Jewish-farm based community on the site of the former colony.

“There’s no contradiction,” said Jonathan Dekel-Chen, a visiting scholar at Rutgers University’s Allen and Joan Bildner Center for the Study of Jewish Life and the Rabbi Edward Sandrow Chair in Soviet and East European Jewry at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. “Jews were farmers in biblical times,” he told The Jewish Link in a phone conversation from Israel. “Jews were shepherds and farmers from the time of Abraham. The Jewish calendar at its core is an agricultural calendar; it told you when to plant and sow.”

In addition to his teaching virtually at Rutgers—scheduled to be in-person until the pandemic—-Dekel-Chen also developed a permanent online exhibition, Jewish Agriculturalism in the Garden State, with the assistance of graduate student Jacquelyne Hankard, detailing the rich history of Jewish farming. Dekel-Chen also spoke in a program sponsored by Bildner over Zoom on October 21 that drew more than 250 viewers.

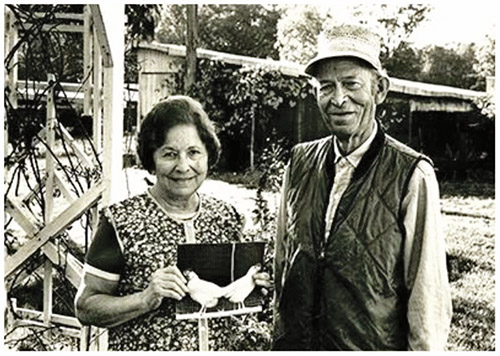

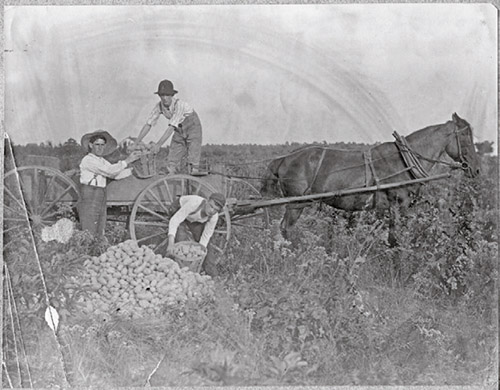

In addition to historical photos and descriptions, the exhibit features interviews, on-location videos, music inspired by Jewish rural life, an index for those looking for specific information and a suggested reading list for those who want to learn more about Jewish agriculture.

Although some photos and documents were provided from other sources, many are being supplied by residents whose families have a connection to farming. Online material can be submitted until January 31. Future oral histories for the exhibit are also planned.

Dekel-Chen called the exhibit “a kind of visual celebration of a part of Jewish life that for a vast majority of the Jewish community has almost entirely been forgotten. It’s one of those historical gems that’s gotten buried in time and memory. Yet the more you dig down into that gem the more fascinating and inspiring it becomes.”

Indeed, from the mid-19th century until the middle of the 20th century, tens of thousands of Jews lived in hundreds of farming communities on four continents. The exhibit, he said, is shining a light on this rich history, with New Jersey as its centerpiece.

“They (colonies) were really intended to create a new kind of Jew by transforming impoverished, victimized town dwellers into productive, strong, tan men and women,” said Dekel-Chen, adding that their signature was the formation of some sort of cooperative to handle matters such as marketing and mutual credit.

“Before the First World War farming was thought of as a respectable profession and a way to make a living,” said Dekel-Chen. “It was a healthier life instead of being in a city where it was common to be crowded into tenements.”

The exhibit jumps from a brief overview of biblical times until agriculture was halted by the Roman expulsion from the Holy Land to the mid-19th century America and Eastern Europe where colonies grew “exponentially” in the late 1800s, spreading to South America and pre-state Israel. Today, Dekel-Chen said the only remaining large-scale Jewish farming communities are in Israel.

The successful Jewish farming colonies enjoyed generous philanthropic support in the West from such places as New York, Philadelphia, Boston and European cities. Jewish farming, especially in New Jersey, owes much to Baron Maurice de Hirsch, said Dekel-Chen, who among other colonies, funded Woodbine in Cape May County, which included the establishment of the first Jewish professional farming school in the country.

The community had an educational foundry and machine shop, two clothing factories, a knitting mill as well as hat and box factories, a community center, two synagogues, mikvah, public schools, sports teams and purchasing and marketing cooperatives.

It had so many Jews from the 1890s until the 1930s that it became known as the first Jewish autonomous community since the fall of the Second Temple. The Woodbine Brotherhood Synagogue was named to the National Register of Historic Places in 1980 and today houses the Sam Azeez Museum of Woodbine History at Stockton University.

Founded as Jersey Homesteads in 1933 as part of the New Deal and renamed after the former president in 1945, Roosevelt in Monmouth County was home to “radical Jewish socialists” who were former needle trade workers from New York and Philadelphia and unwanted in urban centers, said Dekel-Chen. It included a mixed crop cooperative farm, a cooperative factory associated with the International Ladies Garment Workers Union and cooperative retail stores. Roosevelt later became an artist colony.

In other instances, Jews escaping McCarthyism in the 1950s were taken in by farm colonies “out of a sense of Jewish solidarity” even though the residents didn’t share their political beliefs.

Additionally, one of the only ways an immigrant could gain entry into the United States after restrictions were imposed in 1924 until the start of World War II was as a “trained farmer” with a certificate from their home country attesting to the skill. This allowed thousands of refugees, mainly from Germany and Poland, to be placed in colonies—mostly in New York, New Jersey and Connecticut—by Jewish philanthropic agencies, said Dekel-Chen. After the war, Jewish refugees were placed in the colonies by the Jewish Agricultural Society and the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS), allowing them to become self-supporting.

Dekel-Chen said his fascination with Jewish agriculture was rooted in his own childhood, growing up on a farm in Connecticut. He made aliyah at 18. In Israel he became further enamored with kibbutz agricultural life. He still lives on a kibbutz and has been a farmer for decades. His academic research opened him up to the world of Jewish farming enclaves around the world. including the hundreds in central and southern New Jersey.

The exhibition can be viewed at https://bildnercenter.rutgers.edu and includes information on how to virtually submit photos and documents.

By Debra Rubin