The Rama (Orach Chaim 651:1) famously teaches that we should keep the hadassim above the aravot, but does not offer a reason for this practice. The Mishna Berura (651:12) quotes the Levush that the reason is based on Kabbalah, but does not elaborate further.

The Vilna Gaon (Bi’ur HaGra to Orach Chaim 651:1) explains that this practice stems from the well-known midrash that compares hadassim to the eyes and the aravot to the mouth. On a simple level, we can explain the Gra to mean that since our eyes are above our mouth, we should keep the hadasim above the aravot.

Ayin Before the Peh

We suggest that the lesson stems from a terrible failure that caused the destruction of the Beit Hamikdash.

The Gemara (Sanhedrin 104b) states thatRava says that Rabbi Yoḥanan says: For what reason did the prophet precede the verse beginning with the letter “peh” to the verse beginning with the letter “ayin” in several chapters of Lamentations? Since “peh” means “mouth” and “ayin” means “eye,” it is for the spies who said with their mouths (befihem) what they did not see with their eyes (be’eineihem) (from the William Davidson translation of the Talmud).

By placing the hadasim above the aravot, we are reinforcing the message that we must thoroughly investigate a situation before we speak. Our eyes must take priority over our mouths.

A Tragic Modern-Day Example

The following is a tragic modern-day example where we placed our mouths before our eyes (as presented at https://www.shemayisrael.com/parsha/parkoff/archives/kedoshim74.htm).

Rav Shalom Schwadron (Sha’al Avicha I, page 245) relates a pertinent incident that occurred in Yerushalayim during World War I. The Yerushalmis were suffering terrible poverty and starvation. At that time, there lived in Yerushalayim, a very respectable individual who earned his living as a mohel. In the bookcase — in his living room — lay a French gold coin, which was so valuable, it could sustain a whole family for a year.

One day, this mohel’s little boy spotted the shiny coin. He took it and ran to the corner grocery to buy some candy. When his father returned home and saw the coin missing, he immediately investigated to find the culprit. When he discovered that his son had bought some candy with it, it was quite obvious to him that he most certainly had not received candy the whole worth of the coin. And since the storekeeper had not given him change, he immediately suspected him of pocketing the coin and making off with an enormous profit.

The boy’s mother ran to the store and started screaming at the store owner accusing him of stealing the coin. The storekeeper stood there in shock and protested, “I don’t know what you want from me. He didn’t give me any gold coin. He gave me a copper penny!”

The woman, however, was adamant. Just to make sure she went and interrogated the child from exactly where he had taken the coin, and to whom he had given it. There was no doubt that the coin in question was the French gold coin for which the child had received a few measly bits of candy. She continued screaming at the storekeeper. A large crowd gathered to see what the commotion was about and everyone took the side of the woman.

After swallowing embarrassment from all sides, the store owner agreed to go to a din Torah. After hearing both sides of the story, the dayanim decided that the store owner would have to swear. Even though the storeowner was ready to swear, the father of the child said he didn’t want to cause a fellow Jew to swear falsely and so he backed down and withdrew his claim from beit din. Nevertheless, the store owner left beit din in humiliation. From that moment, his mazal turned for the worse and he suffered a life of Gehinnom. He was accused of being a thief and most of his customers stopped buying from him.

Several years after this unfortunate incident, the mohel received an anonymous letter from a young man — a resident of Yerushalayim. He related that several years back, in the midst of the war, he had met this man’s son in the street and spotted him carrying a very valuable gold coin. Being that he had sunk into terrible debt and was literally suffering from deadly hunger, he had taken the liberty of “borrowing” the gold coin with the intent of returning it as soon as his fortune changed. He shrewdly exchanged the gold coin with a copper penny without the boy realizing the switch. It was with this penny that the boy had bought his sweets.

“Now,” concluded the young man in his letter, “my financial standing has improved and I wish to pay up my obligations. I ask of you to forgive me, because it was truly a situation of pikuach nefesh. I was literally starving to death!”

Finally, the truth had come to light. The storeowner was totally vindicated. All this time, he had been a totally upright and honest individual and had never taken any money that was not rightfully his. How true is the dictum of Chazal: “Always judge your neighbor favorably.”

Many years later, a tzaddik who had lived at that time period, elaborated on the lesson to be learned from this incident. He said, “All three characters of this story — the mohel, the storekeeper and the young man — are already in the Next World. They have already stood in front of the beis din shel ma’ala and given an accounting for their actions in this incident, and they probably have come out spotlessly clean. The mohel — in spite of the fact that he had terribly pained the storekeeper — is certainly blameless. He had gone to beit din and the dayanim had obligated his defendant to swear. And the mohel had been gracious in waiving his rights.”

“The storekeeper had probably gone straight to Gan Eden, having suffered such excruciating embarrassment and suffering. The young man, also, had probably been vindicated, as he had acted out of duress due to his personal suffering.”

“Who went to Gehinnom as a result of this story?” concluded the tzaddik in his speech. “All the people who had mixed into someone else’s quarrel and passed a sentence on the storekeeper. Who asked them for their opinion? Why did they have to automatically assume the poor storekeeper of any wrongdoing?”

This is a superb example of the numerous ways in which people pass judgment on others. Unfortunately — all too often — their deliberations aren’t just. This is a result of their eagerness to criticize others. The result is — all too often — an unjust verdict on those they judge.

Conclusion

Experience teaches that this tendency to misjudge others and placing our eyes before our mouths, tragically still plagues mankind. Hopefully, the placing of the hadassim higher than the aravot teaches us to avoid this very damaging behavior. If we succeed and reverse the sins of the meraglim and place our eyes above our mouth, then we will merit the ushering in of Mashiach about whom Yishayahu (11:3) promises will not judge merely by what he sees and hears at first glance. Mashiach attaches priority to his eyes over his mouth, and so should we, if we want him to come!

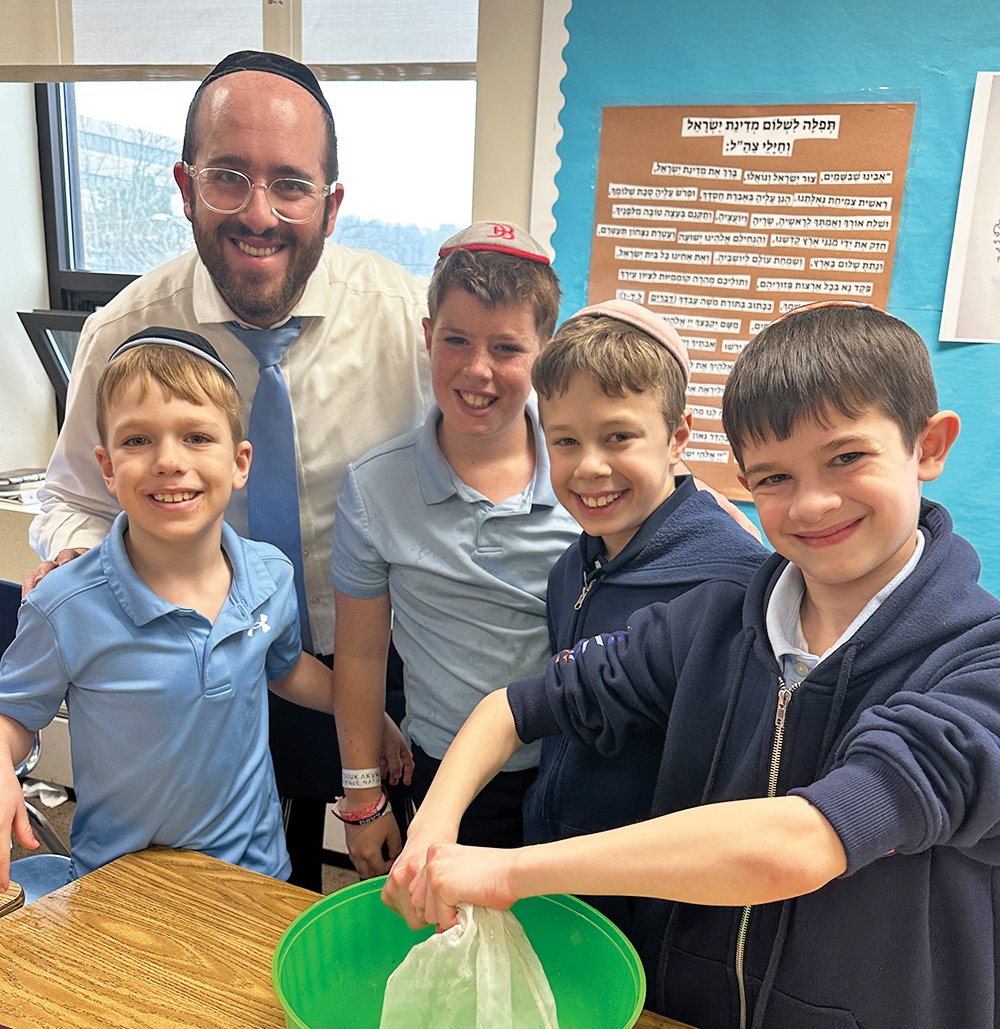

Rabbi Haim Jachter is the spiritual leader of Congregation Shaarei Orah, the Sephardic Congregation of Teaneck. He also serves as a rebbe at Torah Academy of Bergen County and a dayan on the Beth Din of Elizabeth.