(Part 1)

Touted as the “clearest path to the American middle class,” earning a college degree remains a high priority for most Americans. Why? As Wall Street Journal reporter Ben Casselman wrote, college graduates have “lower rates of unemployment, higher earnings, and better career prospects than their less educated peers.”

But because the cost of acquiring a degree has risen faster than almost any other item in the American economy, paying for a college education may be a tougher test than passing the academic requirements of a degree. And the financial challenges can be even greater for those who start college but don’t finish.

A college education has become way more expensive

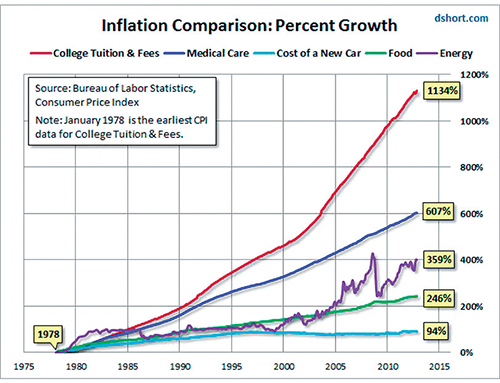

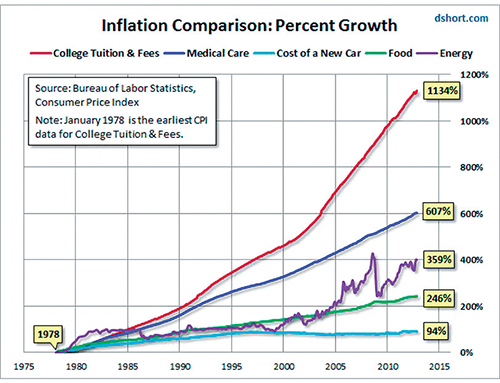

Recent data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics paints a shocking picture (see Fig. 1). Compared to other significant items included in the government’s Consumer Price Index (CPI), the rise in college tuition and fees since 1978 has far outstripped necessities like food and energy, and is nearly double the increase for medical care.

From 1978 to 2012, the average annual rate of inflation for the United States, as calculated by the CPI, was 3.87%, meaning $1.00 in 1978 had the same buying power as $3.63 in 2012. If you plotted this number on the graph, the aggregate inflation rate would be represented by a line slightly higher than the increase in food costs. This means both food and new cars became proportionally cheaper over the past 34 years. Meanwhile, energy, medical, and tuition costs grew faster than the overall rate of inflation and thus were more expensive. Yet even among these three items, the increase in college expenses is the outlier. The rate of growth in college tuition and fees has risen at an annual rate of 7.2%—nearly double that of inflation. As a result, more students are borrowing to pay for college.

As tuition has become disproportionately more expensive, borrowing to pay for it has also increased. Recently published data from the Federal Reserve shows that since the end of 2007, just before the financial crisis occurred, student debt has grown by 56% (adjusted for inflation) while other household debt (mortgages, auto loans, credit cards) decreased 18%. According to a report from the Institute for College Access & Success Project on Student Debt released in October 2012, “Two-thirds of the class of 2011 held student loans upon graduation, and the average borrower owed $26,600.”

Besides economic pressure, educational borrowing has also increased because it is easy to obtain. The same Federal Reserve report found that 93% of all student loans were made directly by the government, “which asks little or nothing about borrowers’ ability to repay, or about what sort of education (students) intend to pursue.” Loan repayments don’t begin until a student has either graduated or is no longer enrolled in school, and in essence, the expectation of repayment is based almost entirely on the assumption of a graduate’s increased earnings. This paradigm is being severely tested by the current economy, which finds many graduates either unemployed or underemployed, and often unable to meet their payments. The default rate on student loans now exceeds credit cards, and some policy makers are beginning to wonder if the metrics of educational borrowing need to be recalculated.

(to be continued…)

Elozor Preil is Managing Director at Wealth Advisory Group and Registered Representative and Financial Advisor of Park Avenue Securities LLC (PAS). He can be reached at [email protected]. See www.wagroupllc. com/epreil for full disclosures and disclaimers. Guardian, its subsidiaries, agents or employees do not give tax or legal advice. You should consult your tax or legal advisor regarding your individual situation.

By Elozor M. Preil