I was raised in a strictly religious home, attended Bais Yaakov and went to a right-wing religious seminary in Israel. My notion of Judaism was related to halachic observance and not a sense of ethnic or spiritual identity. I was not raised with a sense of ahavat ha’aretz (love of the land) or even Medinat Yisrael. We did not celebrate Yom Ha’atzmaut or Yom Hazikaron, and I had no knowledge of the Israel Day Parade or any reverence for service in the IDF. In fact, my year in seminary was my first trip to Israel, and it did not engender any deep emotions of belonging or identity—it may have even solidified my need to live in the U.S.

Fast forward 26 years, I am married, have four children b”H, have lived in eight homes across three states, obtained advanced degrees, had several careers and have traveled back to Israel numerous times, sent children to yeshiva there, made bar mitzvahs and gone on vacations in Israel.Still, no longing or connection, and no deep emotions each time I left. It is the end of 2022 and my husband resolves to fulfill his lifelong dream of making aliyah. While I don’t really feel any particular need or drive to move to Israel, the children will be the right age, and I don’t really feel any antagonism toward moving—I can certainly support his dream. So, we begin the process of filling out paperwork, we purchase an apartment in a burgeoning community, etc—yet, it was merely an intellectual and bureaucratic exercise for me—still no spark.

In the midst of our preparations to make aliyah, my non-religious son already living in Israel decided to make aliyah, as well. When asked why he was interested in aliyah, my son’s response was, “Even if I am not religious in the future, I want my children to grow up Jewish and Israel is the only place where one can have a sense of spirituality, unity and strong Jewish identity even if not actively practicing.” Needless to say, I was very proud of my son’s decision, but his notion of Jewish identity still did not resonate with me. After all, my Jewish identity was founded upon halachic observance, not being surrounded by Jewishness. I preface this article with what surely seems a tangent, to highlight my disinterest in and complete disconnect from the country which my community, my husband and now my son were calling “our homeland” and a cornerstone in their identity.

But, then, October 7 happened. And, as if the horrors of that Black Sabbath were not egregious enough, adding insult to injury, overt and rampant antisemitism reared its ugly head on college campuses, across social media and the world turned completely upside-down. The granddaughter of four Holocaust survivors, this pernicious turn of events led me to instantaneously and viscerally feel there is nothing left in America for my family and we need to live in Israel. Even more so, I felt an overwhelming need to immediately travel to Israel and contribute to our nation and homeland now embroiled in a global war for survival.

On December 25, I flew to Israel on my own. This was my first time traveling to Israel by myself, renting a car, staying in a friend’s empty apartment (thank you “R” family—you know who you are), and navigating the country solo. This endeavor should have caused significant apprehension and even anxiety. Yet, despite war, grief, loss and fear, I was overcome with a sense of belonging, a feeling of tranquility and reassurance that I was going home.

I landed in Ben Gurion on December 26, or October 80, as the Jewish people have come to count each day subsequent to 10/7 referencing the hostages held in Gaza. What used to be a rush toward border control to avoid long lines has become a somber walk met with the faces of the remaining civilian hostages—a stark reminder of the traumatic circumstances in which the Jewish community continues to lead their daily lives.

I went to Israel “armed” with an open heart, the list of chesed opportunities compiled by a local shul, and contacts for a few friends who had made aliyah. What I found was an immense community of brethren, all driven by the same sense of purpose which fueled me. Mi k’amcha Yisrael (Who is like Your nation Israel?)—my phone was rarely silent during my eight-day stay. The war updates and tzeva adom (red) alerts were outweighed exponentially by conversations of those seeking volunteer opportunities and those providing such opportunities … farming, grilling for the IDF, food packaging, visiting displaced families, tzitzit tying and the list goes on. Suddenly, my trip was not so daunting; Waze became my trusted companion and WhatsApp communities and volunteer chats became my extended family.

הַזֹּרְעִ֥ים בְּדִמְעָ֗ה בְּרִנָּ֥ה יִקְצֹֽרוּ

They who sow in tears shall reap with songs of joy. (Psalms 126:4)

On Friday morning, I went out to Ganei Tal, a strawberry farm near Gedera. For five hours I sat pruning a long row of strawberry plants. The farm contained numerous hothouses with rows upon rows of strawberry plants, each requiring tending, pruning and picking. What I often viewed as a “Sunday Fun Day” or Chol Hamoed activity was actually detail-oriented, back-breaking labor. Scattered among the rows were volunteers of all backgrounds, observance levels and nationalities—religious and non-religious; Israelis and foreigners; men, women and children. I met a secular Israeli couple who came to contribute their time along with their cousin from Canada. Nearby, a religious family worked diligently together, and a number of religious American women chatted as they pruned. There is truly no other place on earth where the different “stripes” of people can combine to create a cohesive “plaid,” each individual unique and distinct, yet collectively they create a beautiful masterpiece.

Unexpectedly, notes of Shabbos music began drifting from a volunteer’s phone. The sound of humming to the holy tunes then softly spread across the hothouse as the voices of the men and women, religious and secular, Israeli and foreigner blended together, as if driven by a common purpose, a single identity, a single heartsong.

I left the farm dirty, sweaty and in physical pain from sitting stooped for five hours, but I left with a sense of invigoration, unity and pride (and the WhatsApp contact for some of the Israelis who offered to be a point of contact when we make aliyah).

In Tishrei 2021, Israel’s farmers began the observance of shemitah (sabbatical year) when, putting their faith in God, they leave their land to lay fallow until the following year. I watched videos of farmers singing songs from Tehillim, who upon a heavenly promise of agricultural abundance in the following years, quite literally abandoned their land in service of a higher calling. This Tishrei, a mere two years later, the farmers once again left their farms singing songs of Tehillim in service of a higher calling, the most honorable duty—defending our homeland. In return for their sacrifice, the farmers were blessed with the unity of the Jewish nation who came together performing acts of chesed to help ensure a successful harvest in the coming months.

רְאֵ֨ה נָתַ֤תִּי לְפָנֶ֙יךָ֙ הַיּ֔וֹם אֶת־הַֽחַיִּ֖ים וְאֶת־הַטּ֑וֹב וְאֶת־הַמָּ֖וֶת וְאֶת־הָרָֽע… הַחַיִּ֤ים וְהַמָּ֙וֶת֙ נָתַ֣תִּי לְפָנֶ֔יךָ

וּבָֽחַרְתָּ֙ בַּחַיִּ֔ים לְמַ֥עַן תִּֽחְיֶ֖ה אַתָּ֥ה וְזַרְעֶֽךָ׃…

See, I set before you this day life and prosperity, death and adversity (Deuteronomy 30:15)… I have put before you life and death… Choose life—if you and your offspring would live. (Deuteronomy 30:19)

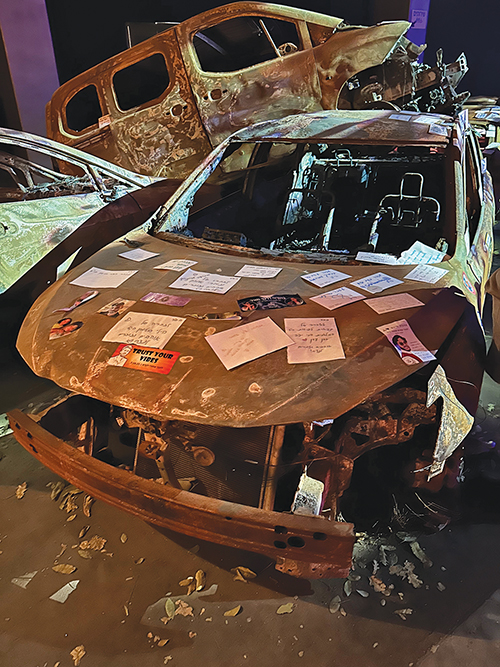

Saturday night I traveled with a friend to Tel Aviv where I attended the Nova 6:28 Exhibit. The remnants of the tents, festival gear, burnt out cars and porta-potties all pierced with bullet holes, were laid out in a recreation of the campgrounds infiltrated by terrorists. The physical scene, augmented by haunting music and the smell of incense, evoked an ethereal sense of hippy peacefulness shattered by primeval violence. Large screens broadcast the WhatsApp messages of the victims’ conversations with their loved ones, the level of fear and horror palpable in their words. At the corner of the exhibit a lost and found section was set up—tables of shoes, reminiscent of the Holocaust Museum or the banks of the Danube. A box of house keys and car fobs for homes and cars too destroyed for further use belonging to deceased people who would never return home. Handwritten notes placed among the exhibits served as both memorials of the souls and testimonials of the deep relationships lost that day.

The Nova Festival attendees were not religious in their lifetime, yet, their deaths poignantly roused the souls of all Jews. The exhibit goers were secular, religious and Haredi, all struggling together to absorb the horrific act perpetrated upon their collective people.

I then traveled to Hostage Square and walked amongst the signs of hostages, a clock counting the number of days of captivity, and thoughtful art exhibits reflecting on October 7. A particularly poignant installation consisted of 230 wooden dowels capped with mirrors arranged in a semi-circle. Each mirror represented a piece of light—a reminder that we are all beings of light; a reminder that there are beings of light being held against their will; and a reminder that hope, like light, will never stop to shine. More resonant yet, each mirror reflects the face of the one looking

into it—a reminder that this could have easily been us instead of them.

I spent the last day of the solar year, closing off 2023, together with my newly-minted Israeli son bearing witness to inhuman evil carnage, juxtaposed with heroic superhuman strength and kindness. My son and I traveled to Kfar Aza, Be’eri and Re’im where we saw firsthand evidence of lights snuffed too soon, and the courage of the Jewish nation to forge forward and reignite the light of the Jewish people so it may endure forever. The contrast of the evil perpetrated upon the nation of Israel against the kindness, munificence and unity demonstrated by the Jewish people truly personifies the words in Deuteronomy: “We have chosen life, so our future generations shall live.”

Upon first impression, Kfar Aza is a beautiful kibbutz blooming with flowers, shrubs and fruit trees. The sky was blue, the sun was shining, and there was a sense of serenity that belied the dangers lurking just a small distance away. My son even commented that he found the kibbutz and idyllic place, an area in which he could picture himself living. But, just a short drive further into the kibbutz brought us face to face with the kibbutz fence breached during the early hours of October 7. The shockwave of airstrikes combined with the sounds of tanks, helicopters and drones interrupted the tranquil façade and brought me back to the reality of my mission and presence. Standing at the mended fence, now wrapped with motion sensors and electric current, Gaza was clearly visible with plumes of smoke arising from the horizon.

I felt a deep sense of duty, if not privilege, to share with the world what I saw, touched, smelled and experienced … Houses riddled with bullets, grenade shrapnel, soot and blood stains. People’s once peaceful, innocent lives, obliterated with savagery entirely incongruent and incompatible with the goodness of humanity.

I stood in the rubble of complete strangers’ homes, absorbing their stories, personalities and character by observing the remnants of their lives in shambles—an electric guitar, riddled with bullets, hanging on the wall; handwritten sheet music strewn across the floor; a bird cage without its inhabitant; a surfboard lying on its side; ashtrays with cigarette butts sitting on a coffee table, as if a group of friends had just been gathered experiencing the joie de vivre of youth and camaraderie which was literally incinerated. A moment in time, frozen forever, never to continue. The homes of the young adults on the kibbutz so closely resembled my children’s apartments—the modest furnishings; the shaver perched on the corner of a bathroom sink; red and black Under Armour high tops at the front door; musical instruments; and laundry in baskets. A haunting thought overcame me: This could easily have been my children.

Every home and building infiltrated by terror bears unique colored markings made by each of the IDF, the bomb squad and Zaka, communicating what was found within the walls of that structure—whether unexploded ordnance, human remains or other collectible evidence—and whether it was now safe to reenter. The markings are a haunting reminder amid the destruction of what had truly occurred on October 7.

The true beacon of light and goodness in the sea of darkness along the Gaza border are the angels of Zaka, bringing dignity to every victim, exhausting all physical and emotional effort to collect and recover the last vestiges of human remains for identification, notification and burial. Every bit of blood and tissue was searched for and collected to be buried. Human ash was literally vacuumed up to preserve the memories of those tortured and slaughtered. These saintly volunteers, engaged in avodas hakodesh (holy work) and true chesed shel emes painstakingly sifted through the trail of ash, dust and human fragments left in the wake of savagery so monstrous, demonic and unearthly in nature, it is akin only to the hell Dante envisaged.

We left Kfar Aza for a road outside Be’eri which serves as a corridor for the soldiers entering and leaving Gaza. The energy along this road was uplifting and charged with positivity, something we sorely needed following the emotionally harrowing morning on the kibbutz. A food truck at the side of the road provides sustenance to these young heroes free of charge. My son and I, along with other Americans, ran alongside military vehicles filled with youthful, determined soldiers facing their somber mission just ahead, and we distributed snacks and cigarettes. The soldiers did not stop expressing their gratitude for the support as we all continually chanted “Am Yisrael Chai.” A family of brethren unified, not in their religious observance, but in their spiritual identity, love for the Land of Israel and sorrow for our collective loss.

We ended our day as the sun was setting at what has become known as the “car cemetery,” a single location to which all the cars on the road along the Nova festival in Re’im, and from some of the kibbutzim—more than 3000 in total—were brought for burial as they contain trace amounts of human remains. The wall of burnt out, mangled heaps of metal stacked many feet high and extended in a line as far as the eye could see. The distorted and warped metal mimicking the excruciating death masks of their passengers fearfully trying to escape for their lives. Their twisted remains, mere shells of automobiles, a foil of the unrecognizable charred corpses. The sun, glowing a deep orange, went down over the wall of metal—as if kissing them in mourning as it set on the last day of a horrific year.

Needless to say, I did not sleep that Sunday night, though I wasn’t kept awake by the sounds of New Year’s fireworks, my heart and mind were heavy with my experience of the day. But, all I could think was, “we will persevere, we must!”

I woke up the next morning and resolved to forge ahead and continue to engage in acts of chesed. I walked to a nearby shul and learned to tie tzitzit, yet another activity I never imagined having the opportunity to perform. I sat amongst men, women and children with mixtures of English, Hebrew and French heard as people diligently worked to do their part to diminish the 100,000 pair deficit the IDF was encountering. The camaraderie, energy and commitment were electric and deeply healing to my weighted heart.

Leaving Israel was so much harder than I ever experienced or even imagined. Wearing a “Our heart is captive in Gaza” dog tag, walking to my departing flight on October 88, past the moving sidewalks lined with the pictures of hostages—identical in number as upon my arrival—I experienced a deep sense of dismay. I genuinely believed that through the sheer power of prayer, hope, and mitzvot, Klal Yisrael could have manifested the return of our precious hostages. Yet, eight more days were added to the “month of October.” The number on Rachel Goldberg’s daily sticker increased by eight. How could more than a week have gone by without the return of a single innocent captive?! How has our Jewish family not awoken from this nightmare?!

אַחֵינוּ כָּל בֵּית יִשְׂרָאֵל, הַנְּתוּנִים בְּצָרָה וּבַשִּׁבְיָה, הָעוֹמְדִים בֵּין בַּיָּם וּבֵין בַּיַּבָּשָׁה, הַמָּקוֹם יְרַחֵם עֲלֵיהֶם, וְיוֹצִיאֵם מִצָּרָה לִרְוָחָה, וּמֵאֲפֵלָה לְאוֹרָה, וּמִשִּׁעְבּוּד לִגְאֻלָּה, הַשְׁתָּא בַּעֲגָלָא וּבִזְמַן קָרִיב.

As for our brothers, the whole house of Israel, who are given over to trouble or captivity, whether they abide on the sea or on the dry land, may the All-present have mercy upon them, and bring them forth from trouble to enlargement, from darkness to light, and from subjection to redemption, now speedily and at a near time. (Prayer for Captives)

I fervently hope and pray for the safe return of the 130+ precious souls from Gaza; for the protection of our soldiers battling for the existence of our homeland, and self-determination for our people; and that the deaths of those slaughtered on October 7 will be avenged.

My return from Israel fell out during the week in which we began reading from Sefer Shemot, the book of galus and geula (exile and redemption). Sefer Shemot is the embodiment of contrast, of the dialectic of opposing concepts—exile vs. redemption, good vs. evil, life vs. death. This chapter of biblical history teaches us to embrace two competing notions simultaneously, but ultimately, to choose good, life and blessing. I can’t think of a better way to sum up my experience in Israel, amongst my extended family in my newly appreciated homeland. I now yearn to return home to Israel long before our aliyah date—a mere 20 months away.

Chana Sytner is a practicing commercial real estate attorney currently living in Bergenfield until she and her husband, Ari, make Aliyah in the summer of 2025.