Those of us who have been pregnant will recall that when we make our initial visit to the obstetrician, one of the first things that is recommended is that we take a vitamin supplement. This prenatal vitamin is folic acid, one of the vitamin B family.

Folic acid is important in the first trimester in early development of the neural system in the fetus. Perhaps the most important birth defect that occurs is neural tube defects (NTDs), which include spina bifida and anencephaly, and occur in 1-2/1,000 births in the absence of folate supplementation. In truth, there are not many people in the U.S. who are folate deficient on a dietary basis, and most others do get prenatal care and vitamin supplements. Nonetheless, there do exist individuals under the radar who have poor diets/nutrition, don’t get prenatal care, and yet become pregnant; in this population, the risk of NTDs is inordinately high.

In 1992, the CDC had the idea of fortifying cereal grain with folic acid so as to remedy and ameliorate this problem and to help this set of pregnancies. The addition of folate to these grain products—breakfast cereal, commercial baked goods, pasta, rice, grits—began at that time, spread rapidly, and became mandatory in 1998.

The impact on NTDs was outstanding—the rate of NTDs nationally fell annually by about 40%-50% since folate fortification was implemented, and has been an outstanding success of the Public Health Service. The number of NTDs has generally been reduced in the U.S. by about 1,500 annually. Canada implemented folate fortification in tandem with the U.S. and they achieved a similar improvement in birth defect reduction.

But, unfortunately, there is no such thing as a free lunch. Folic acid has a complex relationship with colorectal cancer (indeed, with other cancers as well). Multiple studies have suggested that folate is protective against colorectal carcinogenesis in those with low or normal folate levels.

But what happens in an environment when the entire population is suffused with high levels of folate? There is at least some evidence to suggest that under those circumstances it might act as a stimulant to carcinogenesis.

In the 1940s, on two occasions, investigators inadvertently gave very high doses of folate to patients with acute leukemia. In both instances, this led to rapid acceleration in the growth of the leukemic clones. This observation led to the introduction of antifolates—specifically aminopterin and later methotrexate—as chemotherapeutic agents, which had great success in the treatment of leukemia and later other malignancies.

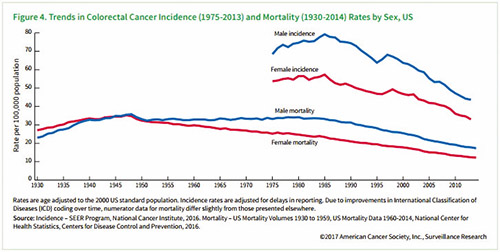

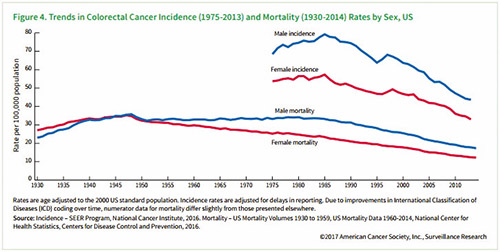

In this context, the reader is referred to the figure that shows the incidence rates of colorectal cancer in the U.S. before and after folate fortification. At the time, and continuing until now, colorectal cancer rates were declining because of the increasing use of colorectal cancer screening and the removal of adenomatous polyps, a highly efficacious intervention. But the figure illustrates abrupt upticks in its incidence in the United States in the late 1990s, beginning about 1996, following the widespread adoption of folate fortification. It represents an increase of about 2-4 cases/100,000/year and it seems that a new plateau was set and persisted.

Its temporal association to the institution of folate fortification led some to speculate that there is a causal link between the two. Others believe that changes in screening rates are responsible for the upticks though there was no obvious change that occurred that was clearly responsible for the abrupt change. It is alleged that there were changes in Medicare policies that increased screening several years before and led to the uptick, but Canada had the same uptick in colorectal cancer incidence as the U.S. so that is hard to jibe with this explanation. Another argument against this hypothesis is that the uptick occurred too rapidly after the folate fortification, and that has merit. In addition, many folate supplementation studies do not show an increase in colorectal cancer rates. Certainly, many respected experts do not believe folate is responsible for this blip in colorectal cancer. And over 40 countries globally have implemented folate fortification.

I add one more piece of information. In 2000, Chile introduced folate fortification to its population. There was a satisfying drop in the rates of NTDs, similar to Canada and the U.S. However, a paper some years later reported that the rate of colon cancer increased there as well between 2001 and 2004.

Whether folate fortification is indeed the culprit in raising the colorectal cancer rate I remain uncertain—not every scientific question has a clear-cut answer. But as an interesting exercise for a graduate school class for public policy planners, let us assume it is guilty. Should a program that prevents very severe birth defects in 1,500 infants annually be abandoned because an extra 2,000-3,000 mostly older people get a cancer which is mostly (75-80%) cured? Hmm…

Alfred I. Neugut, MD, PhD, is a medical oncologist and cancer epidemiologist at Columbia University Irving Medical Center/New York Presbyterian and Mailman School of Public Health in New York.

This article is for educational purposes only and is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment, and does not constitute medical or other professional advice. Always seek the advice of your qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or treatment.