The night grew pitch black as 20-year-old Taraneh Reyhanian, her brother Daryoush and her fellow runaways made their slow march through the desert towards Pakistan––towards freedom. But they hadn’t traveled long before they heard the shouts of Iranian soldiers telling them to stop in their tracks. In minutes the runaways became prisoners as the soldiers lined them up and held them at gunpoint.

Reyhanian, now Mrs. Yaghoubzar, was one of many Jewish Iranians who were smuggled out of their home country during the Iranian Revolution in 1979.

More than 60 years ago, Reza Shah Pahlavi took power over Iran. The last shah, which literally translates to “king,” in Iran was Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, who helped establish many industrial and social reforms during his reign from 1941 until 1979. Jews in Iran found they were able to celebrate their religion in comfort.

However, many Muslims at the time, including Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, wanted Iran under Islamic rule, and others thought the shah’s power was too oppressive. Many Iranians began to protest the shah’s rule and on January 16, 1979, the Shah was forced to flee Iran. Just 14 days later, Khomeini usurped the government and became Supreme Leader of Iran.

Under Khomeini’s rule, Jews felt too stifled to observe their faith openly. Citizens in general were not granted civil rights under the new dictatorship. The government was fearful of another overthrow and in the midst of a civil war, and Khomeini set out to kill anyone suspected of being a member of an opposing political party such as Mojahedin or Tudeh, which had different ideologies than Hezbollah.

“They killed a lot of young kids,” Yaghoubzar recalled. “They would grab them off the street and after holding them for a few months they would just shoot them without a trial.”

Many Jews left the country while they could and many were smuggled out illegally, their final destination being Israel or America.

Yaghoubzar ’s parents had already sent her two older siblings to America in 1979. Yaghoubzar and her younger brother were still in Iran when Khomeini usurped the shah’s rule and when, a year later, the Iran-Iraq War began.

Yaghoubzar and her brother bought a two-way ticket to Zahedan, an Iranian city on the border of Pakistan, in order to lessen any suspicion of their departure. Her mother flew with them, all the while worrying whether or not the smuggler could be trusted. Despite her mother’s request, the smuggler could not reveal any references or proof of his credibility at the risk of endangering the lives of those he’d helped already.

Yaghoubzar separated from her mother at an open-air market in Zahedan. They were not allowed to say goodbye or give away any signs that they were parting for an indefinite period of time. The smuggler in charge of Yaghoubzar, her brother and other escapees met them in the market where, with a flick of the wrist, he pointed them in the direction of a pickup truck waiting for them.

They were dropped off at a small house to wait until the smuggler had collected all of the refugees making the trip. This group grew to about 15 people. They waited until it was dark out before they started traveling. They weren’t allowed to leave or use the bathroom, which was located in an outhouse, for fear of drawing any suspicion.

Once it grew dark enough, a different driver came to gather them into the truck. He threw a blanket over them and told them not to breathe a single word. To Yaghoubzar and her fellow travelers’ misfortune, the driver of the pickup truck was new to the job, and after an hour of traveling at night towards a destination with which he was not familiar, he had them all lost in the desert. The truck became lodged in tar, and when they continued their journey on foot, they soon found themselves sinking into it as well. They managed to pull themselves out only to be stopped by Iranian soldiers ready to kill the absconders, or so they thought.

The soldiers gave them water to drink, a common custom the soldiers followed that preceded the murder of their victims. What Yaghoubzar didn’t know was that the soldiers had no intention of killing her or anyone else.

The soldiers’ actual plan was to hold them hostage until the smuggler could bring back enough money to convince the soldiers to release them. They kept the refugees in a ditch in the desert, and searched them repeatedly throughout the night. She spent her first night of escape as a prisoner unsure of her fate.

“That night when we were in the pit, I had never seen the sky so beautiful with so many stars,” Yaghoubzar said. “I said to myself, ‘Hashem, if you have such a beautiful universe, please save us––don’t let us die here.’”

Her prayers appeared to be answered, and their journey continued. It took 12 hours for them to reach the border. The travelers arrived safely at the border of Pakistan where they found the same smuggler from the open-air market pacing worriedly. The group was a day late due to the night spent in the pit.

“Do you see my shoes?” he asked as they got off the truck and into the scorching heat of the sun. “I bought these shoes when I came last week in Tehran.” He pointed to the soles, which were worn down so thin from pacing that Yaghoubzar could see his feet under them. “I didn’t know what to tell your parents––I thought you were dead.”

They again waited until dark to travel. They were smuggled in another truck, along with other illegal goods such as cigarettes, rugs and barbed wire. They drove through many checkpoints before they eventually made it into Pakistan.

Because the driver used the money he had to bribe the soldiers at the checkpoints, the smuggler couldn’t afford to fly them to the U.S. embassy in Karachi. They were given rides in buses through the passing villages, but had to do most of the traveling on foot in the hot desert. Water was scarce and the travelers were at the mercy of whoever hosted them during each night of travel. They were told not to speak as they traveled during the day lest someone discover that they didn’t belong in their village or in Pakistan at all. They were given clothes to wear that helped them better fit in––baggy pants, shirts and chadors for the women.

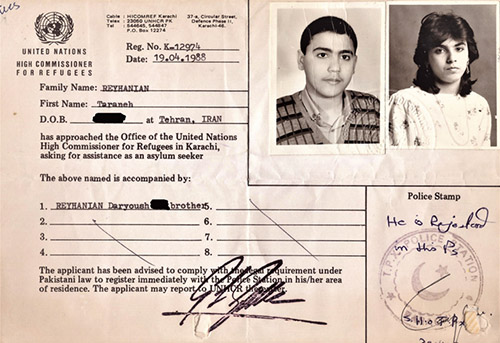

After seven days they finally reached the embassy in Karachi, where they received their group visas and were instructed to carry them on them at all times.

“For the entire seven days our parents had no clue what happened to us,” Yaghoubzar said. “They were told they would hear from us [in] less than 36 hours but due to our capture it took longer––my parents were sick with worry––they thought we had been killed.”

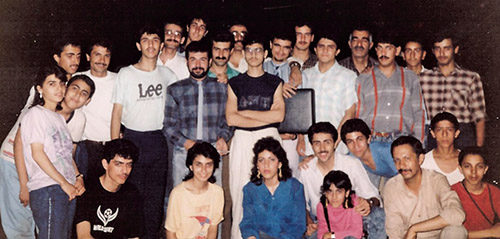

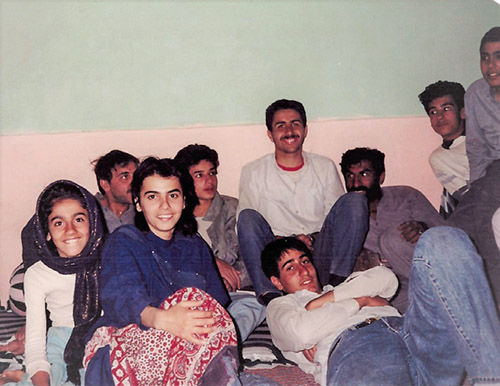

After the trip to the embassy they arrived at the hotel in Pakistan, where they stayed for 30 days, though it was ill kept and infested with rodents.

“Life in Pakistan was very hard,” she said. “The water was contaminated, and it was so hot outside that when you walked on the streets you could feel the heat from the ground burn your feet.”

They had no kosher meat with the exception of what they were given by a Jewish Israeli couple living in Pakistan that helped Jewish refugees. Yaghoubzar and her brother celebrated Shabbat and ate kosher chicken every Friday night.

Yaghoubzar and her brother were able to get a visa to Vienna, with the help of HIAS, the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, an organization dedicated to ensuring the safety of refugees. Yaghoubzar spent 11 months in Vienna learning everything from Jewish halachot to the tragedy of the Holocaust, a part of Jewish history she had not previously known.

HIAS also helped train her for her interview with the American embassy, where she described her reason for escaping and what family she had to vouch for her in America. Yaghoubzar and her brother eventually made it to the U.S. in April 1989. She was hired in the radiology department of Beth Israel Hospital as an x-ray technician and worked there for 14 years. She stayed with her siblings in their apartment in Queens before eventually getting married and moving to Paramus where she now resides with her family.

“We were the lucky ones,” Yaghoubzar said of her and her brother’s journey. Many other people did not have the good fortune to make the trip alive or unscathed. “With all our difficulty we still kept our Jewishness and we learned a lot.”

“I consider myself very lucky to be able to raise my kids in a place where they can attend a yeshiva and keep their heritage freely,” she concluded. “Things like that were impossible for me as a kid. I was never granted that same fortune.”

Elizabeth Zakaim is a student at The College of New Jersey and a Jewish Link contributor.

By Elizabeth Zakaim