Henry Kissinger recently passed away at the age of 100. Blessed with lucidity until the very end, he gave an interview to the Jerusalem Post a mere two months before his death. I was going to write an article posing the question whether a street should be named in his memory but, lo and behold, the question is moot as Henry Kissinger Street can be found in Rishon LeZion. The obvious next question is: Should a street have been named for him?

Kissinger’s relationship with Jews and the State of Israel was complicated, and experts disagree whether he was a friend, a foe or something in between.

Henry Kissinger was an assimilated Jew who lacked pride in his Jewish identity and habitually disparaged Jews in public settings. Some of his more infamous statements include: “I’m going to be the first Jew accused of antisemitism” (he was apparently oblivious to the term “self-hating Jew”); “If it were not for the accident of my birth, I would be antisemitic,” and “Any people who has been persecuted for two thousand years must be doing something wrong.” Kissinger also mocked politicians who defended Jews and Israel, such as the legendary Daniel Patrick Moynihan, and once scornfully inquired whether Moynihan wanted to convert to Judaism.

In 1975, otherwise mild-mannered Rabbi Norman Lamm lambasted Kissinger. After mentioning several of Kissinger’s previous anti-Jewish indiscretions, Rabbi Lamm focused on Kissinger’s trip to his native city of Furth, Germany, where he failed to even mention the Holocaust. Rabbi Lamm minced no words, when stating: “All Jews living today are alive only by a twist of fate—a twist of fate that, at the same time, condemned six million to death. The Kissingers were lucky, very lucky. Could there be no mention, then, of those less fortunate than they, the Jews of Furth who never got out on time? Does one just forget them?” Rabbi Lamm added, “He wants not to be a part of our people—its history and its destiny, its suffering and its joys. So be it. … Let us grant him his obvious wish to be dis-united with us.”

Others took the middle ground and viewed Kissinger as a “conflicted” Jew who was uncomfortable with, and probably ashamed of, his heritage.

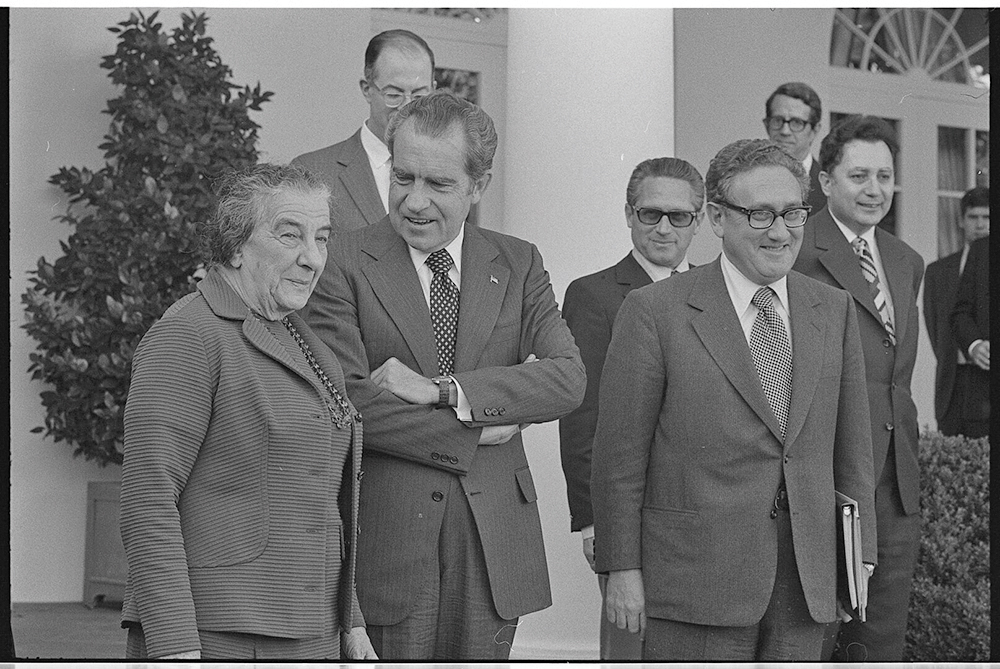

Understandably, Henry Kissinger was looking out for the interests of the United States, and therefore sought to use the Arab-Israeli conflict to advance the US’s objectives. However, he sometimes, possibly unknowingly, compromised Israel’s security. The most well-known example occurred on Yom Kippur morning in 1973. Kissinger was awakened by Golda Meir who informed him that Egypt was about to commence a major assault against Israel and gave her commitment that Israel would not launch a preemptive strike.

Kissinger immediately called the Soviet ambassador to inform him that the Israelis had no intention to attack and warned that the USSR should not make “a precipitous move.” Kissinger then called a senior Israeli diplomat in Washington and cautioned against taking any preemptive action “because the situation will get very serious if you move.” Finally, Kissinger called the Egyptian foreign minister and informed him that he warned the Israeli ambassador, “If Israel attacks first, we would take a very serious view of the situation and have told him on behalf of the United States that Israel must not attack, no matter what they think the provocation is.” How thrilled Sadat and Brezhnev must have been upon hearing how Kissinger’s helpful actions in restraining Israel supported their war efforts.

Nevertheless, although no one would regard him as an unwavering supporter of Israel, a few archived conversations cast Kissinger as a friend of Israel. For example, in 1971, Kissinger guided Deputy Prime Minister Yigal Alon how to protect Israel against the US State Department’s efforts to give back land it gained in the Six Day War. These experiences, though infrequent, were probably the reason why Kissinger received Israel’s Presidential Medal of Honor in 2012 for his “significant contribution to the State of Israel and to humanity.”

Kissinger was a complex person and his complicated relationship with Israel doubtless reflected his inner turmoil. Israel’s leaders, though, evidently understood Kissinger’s conflicts. When Henry Kissinger told Golda Meir that he considers himself “an American first, Secretary of State second, and a Jew third,” and Golda legendarily responded that “In Israel, we read from right to left,” perhaps she was also reminding him of the values of his buried heritage.

Gedaliah Borvick is the founder of My Israel Home (www.myisraelhome.com), a real estate agency focused on helping people from abroad buy and sell homes in Israel. To sign up for his monthly market updates, contact him at gborvick@gmail.com.