Technology has changed the classroom forever. Gone are the days when a teacher would assign students a chapter to read followed by frontal instruction and note taking. Smartboards, iPads, and the unbelievable explosion of what is available on the web has changed how we teach. More significantly, it has changed how students learn. Attention spans are shorter. Instant data availability and fast-moving videos mock the days when students actually had to look things up. School libraries are being phased out. Library Science has been replaced by digitization, and access to everything literally is at your fingertips. However, the teacher of history, and in particular, Jewish history, can take advantage of this phenomenon and make Jewish history come alive in ways undreamt of by previous generations of teachers.

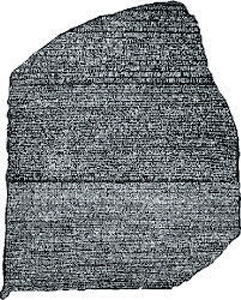

Most kids hate history. Names, dates, facts, etc. are boring. The connective tissue is missing making it drier than an ancient bone. I didn’t like history until graduate school. I hated memorizing Marx and Margolis. However, once I was introduced to the texts and sources of Jewish history–those historians use to write history–a whole new world opened up for me. I became like the Sherlock Holmes of historical research: nothing escaped my attention. Texts, legal documents, rabbinic commentaries, responsa, letters, bills of sale, contracts, coins, memoirs, diaries, paintings, sculptures, maps, photos, newspapers, ship logs, coins, artifacts made history come alive.

When I started teaching, I used photocopies, thermal stencils, maps, and whatever I could get my hands on. I had the old-fashioned canvas maps on rollers. I made slides from pictures in various books. I made transparencies and used the overhead projector, the opaque projector for 3D items, stamps, etc., and even film strips (who remembers them?). I used collections of primary sources such as Jacob Marcus’s The Jew In The Medieval World; Sourcebook of Jewish History, by Hoexter and Jung; Like It Was, Like it Is, Mellon and Chrisman; A Treasury of Jewish Letters, Kobler; Eyewitnesses to Jewish History, Eisenberg, Goodman, Kass; A Documentary History of the Jews in The United States, Schappes; material from the American Jewish Historical Society, anything by Jonathan Sarna, etc. There is so much available now online. A teacher need not be a professor of Jewish history, just someone with a good basic knowledge and the ability to find primary sources on the Internet.

Many collections have source materials already translated. Advanced students may be able to use the many excellent collections in Hebrew. I brought in whatever artifacts I could find. Museum trips and movie clips were always included. National Geographic, the magazine as well as their film library, as well as so many selections available from various public television cable stations, are a treasure trove of source material. Today there is so much more available online and in new collections of source materials.

It is also important to remind students what was going on in the rest of the world. The emergence of Hasidism, for example, took place at the same time as the fight for American independence. There are many valuable timelines available on line from general and Jewish sources to show these parallel developments. A Google search for Jewish history timeline will yield over 4,000,000 results.

For some really good charts see: http://alturl.com/wpfjw.

Integrating Jewish and general history is an intriguing idea but may shortchange both. Also, it requires an extremely and exceptionally talented and well-informed teacher.

All standard Jewish history textbooks can serve as an outline to be supplemented by the items mentioned above. Israeli Jewish history textbooks are far superior but are beyond the language skills of most American students, but should be used by teachers of Jewish history who can handle the material.

A few caveats:

• Since a sense of history doesn’t exist for most young children, serious study of Jewish history should not start until 7th grade.

• The four years of high school lend themselves to a four-part comprehensive curriculum: ancient (post-biblical to Geonim), medieval (Geonim to French Revolution), modern (Enlightenment, Zionism, Holocaust), and American Jewish history. (Full disclosure: I designed and taught this four-year cycle at Frisch from 1972–1976.)

• Another possibility is to focus on major personalities and movements if a full curriculum is not an option.

• Ideally, the teacher should have an advanced degree in Jewish history in order to be able to access and properly utilize the source materials.

• Creativity in the selection of materials to use is a sine qua non.

There is so much material available: from photos of chariot wheels on the bottom of the Red Sea to Abarbanel’s introduction to his commentary on Sefer Melahim, where he writes as an eyewitness to the Expulsion of the Jews from Spain. Primary sources can be put together in a booklet, but with the ubiquity of iPads this may no longer be necessary–plus it gives the teacher more flexibility with Smart Boards. (I am assuming that all teachers receive training in the use of Smart Boards and that by now most classrooms are equipped with them or with the next generation of interactive plasma screens, Bright Link, etc.)

Once there is content there must also be context. Wrestling with the big questions about the ebb and flow of Jewish history is also a desideratum. But that is true as well about the study of Tanach, Talmud, and Halacha. The what is easier to communicate than the why. This too is an educational challenge in a crowded curriculum.

Jews lived all over the world, in many different cultures, and wrote in many languages. It is challenging and takes more prep time to teach from primary sources but it is more rewarding. Why should students have to rely on someone else’s opinion and interpretation about the Church’s attitude towards Jews when they can read the papal bulls themselves? Why shouldn’t students be exposed to the documents showing that Christopher Columbus was Jewish? What did Antiochus look like? Alexander the Great? Why was Chanukah originally celebrated like Sukkot? Where did “Jewish” names originate? How can rabbinic responsa or the Geniza be used as a source for Jewish history? How did Jewish soldiers during the Civil War observe Passover? When and why did Jews in certain Russian communities eat green matzot (made from peas)?

Today, there are many talented and creative Jewish history teachers who are using primary sources as vehicles for instruction. Teaching from primary source materials is challenging–and full of excitement. As should be the students who study Jewish history. To find out more about specific history curricula and programs that have been proven successful around the country, contact me directly at [email protected].

Rabbi Dr. Wallace Greene has had a distinguished career as a Jewish educator. He has taught children, teens, and adults. He was a college professor, day-school principal, and director of two central agencies for Jewish education, including our own community’s Jewish Educational Services, for over a decade. He is the founder of the Sinai School, and has received many prestigious awards including the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Lifshitz College of Education in Jerusalem and The World Council on Torah Judaism. He is currently a consultant to schools, non-profit organizations, and The International March of The Living. He can be reached at [email protected].

By Wallace Greene