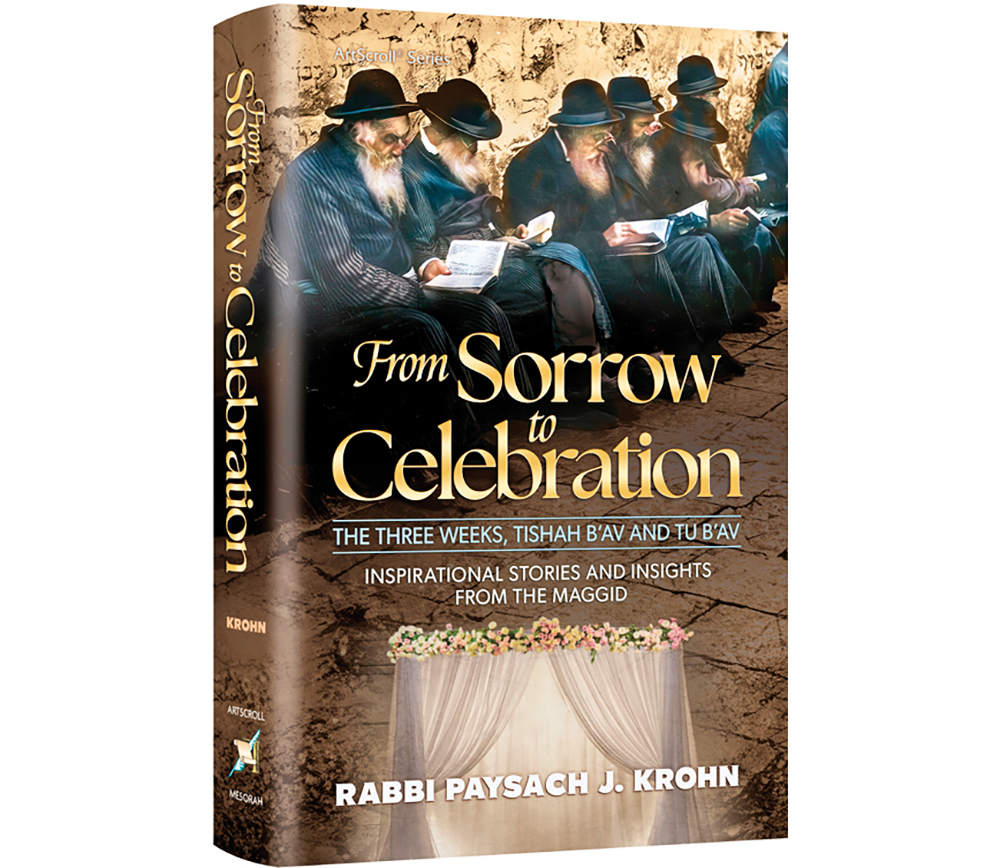

Excerpting: “From Sorrow to Celebration” by Rabbi Paysach Krohn. Mesorah Publications Ltd. 2024. Hardcover. 600 pages. ISBN-13: 978-1422641118.

(Courtesy of Artscroll)

Shabbos Sanctity

It is interesting that of the sixteen pesukim read in the haftarah on fast days (Yeshayahu 55:6-56:12), three mention the importance of shemiras Shabbos. The Radak (ibid. 56:2) explains that Yeshayahu HaNavi was addressing the tribes that had been exiled, urging them to strengthen their Shabbos observance so that they would be redeemed and permitted to return to Eretz Yisrael. As Chazal teach, “Yerushalayim was destroyed only because Jews desecrated the Shabbos” (Shabbos 119b).

It behooves us then, during this mourning period of the Three Weeks, when we read this haftarah on Shivah Asar B’Tammuz, that we make a concerted effort to improve our Shabbos adherence.

The following story depicts a man’s love for and dedication to Shabbos. It was told to me by Dr. Ephraim Bartfeld, a pediatrician in Waterbury, Connecticut, about his paternal grandfather, Yosef (Jose) Bartfeld, who lived in Mexico and had great mesirus nefesh for Torah and mitzvos.

In the 1960s, Yosef Bartfeld and his wife Baila (Berta) had a thriving business in the central shopping district of Mexico City. They owned a leather goods and silver shop at the corner of Avenida (Avenue) Juarez and Bulevar (Boulevard) Alameda. The shop was a major tourist attraction, as it had a beautiful array of popular Mexican souvenirs, medallions and memorabilia. Many shoppers who were attracted to the Bartfelds’ Tienda de Plata (silver shop) would also browse and shop at neighboring stores as well.

Mr. Bartfeld’s store was closed on Shabbos. One day, officials of the local Mexican City Business Council instructed him to keep his store open on weekends. They claimed that because the prestigious Tienda de Plata was closed, the surrounding stores lost business, as fewer customers came to shop in the area.

Mr. Bartfeld told the officials that there was nothing more important to him than Shabbos, and money was not what he lived for. He assured them that he would come from his home, a block and a half away, the moment Shabbos was over to open the shop and keep it open until midnight.

That did not satisfy the delegation; they insisted that merely opening on Saturday night was not good enough. Most people shopped during the day, and there was not enough street traffic on Saturday night to compensate for the daytime losses. They threatened to fine Mr. Bartfeld for every Shabbos the shop was closed. They left the shop angrily after issuing their warning.

The next Friday afternoon, Police Officer Roberto Beltran* approached Mr. Bartfeld and asked if the shop would be open on Shabbos. Without hesitation, Mr. Bartfeld responded that as a religious Jew he could not possibly violate the Sabbath.

Roberto whispered to Mr. Bartfeld, “Look, this is my district; if you take care of me, I’ll take care of you, and the authorities will leave you alone.”

Mr. Bartfeld understood the implication. If he paid the officer, he would not be reported for keeping the store closed. It was common knowledge that if someone was stopped for going through a red light, the driver merely had to hand the policeman a certain amount of billetes de dólares (dollar bills) and there would be no summons. This interaction applied to many other infractions. It was considered part of the officers’ income, since their salaries were low. Cynically, it was regarded like tips to waiters, a normal supplement to their salaries.

Mr. Bartfeld nodded to Roberto, promptly put money into an envelope, and gave him the first payoff. This went on regularly for months.

The corner of Avenida Juarez and Bulevar Alameda was a busy intersection. One Shabbos afternoon, there was a horrific car crash when someone ran a light and a car careened onto the sidewalk and crashed through the huge plate glass window of Mr. Bartfeld’s store. Glass was strewn everywhere and the store was totally unprotected from looters.

Fernando Hernandez,* the owner of a neighboring store, hurried to Mr. Bartfeld’s nearby home and told him about the crash and the shattered storefront. “It is my Sabbath and I am not going near my store,” Mr. Bartfeld said to the astounded Fernando. “I’ll be there tonight after the Sabbath ends.”

That night, after Havdalah, Mr. Bartfeld rushed to his store. He was stunned by what he saw! Standing outside in the doorway of his store with his hand on his gun was Roberto Beltran, the police officer whom Mr. Bartfeld had been paying every week, now ensuring that no one entered the store. He had been there for hours, protecting the premises and waiting for Mr. Bartfeld to return.

Mr. Bartfeld was shocked! “What in the world are you doing here?” he asked Officer Beltran.

“I know how much the Sabbath means to you and I did not want you to suffer any losses because of your religion. Now that you are here, I will be on my way.”

Mr. Bartfeld would often say afterward, “Had I come to the store that Shabbos afternoon, there was nothing I would have been able to do to protect the store. Only the policeman with the drawn gun could have done that for me.”

On Shabbos, there are many who sing, “Ki eshmerah Shabbos kel yishmireini, If I safeguard Shabbos, Hashem will safeguard me.” This episode is prueba positiva — proof positive.

•••

Yosef and Baila Bartfeld were so committed to the Torah growth of their children that even before his bar mitzvah they had sent their son, Yisroel Yehuda (Leon), to the Telshe Yeshiva in Cleveland. (Dr. Bartfeld, who told me this story, is his son.) Their other son, Rabbi Avrohom Bartfeld, who learned in Gateshead, Ner Yisroel, and Mesivtha Tifereth Jerusalem, is today the Rav of Congregation Bais Dov Yosef in Toronto.

For the sanctity of Shabbos, Hashem showered blessings on His loyal servants.

It’s food for thought on a fast day.

*Names were changed

Reprinted from ‘From Sorrow to Celebration’ by Rabbi Paysach Krohn with permission from the copyright holder, ArtScroll Mesorah Publications.