Germany is known for a strong state-level commitment to atoning for its Holocaust past, manifested through formal ceremonies, museums, and monuments. At the same time, in a seemingly growing trend, the extremist anti-Israel analogy of the Israeli government to the Nazi regime can often outweigh Germans’ Holocaust guilt.

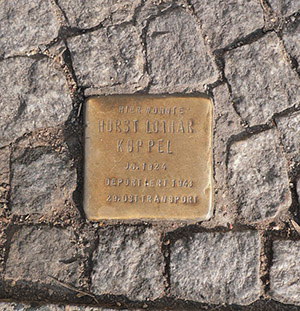

Earlier this summer, a debate engulfed the German city of Munich over whether to embed the “Stolpersteine”—plaques naming Holocaust victims that are also known as “stumbling block” memorials—into street sidewalks. In July, Munich’s city council voted to ban the memorials due to complaints that stepping on such stones would be an insult to Holocaust victims.

According to reports, some representatives of the Stolpersteine initiative, which exists in multiple other German cities, have exhibited anti-Israel sentiment. For instance, in the city of Kassel, one organizer said in 2014 that “death is a master today from Israel” and that there should be “stumbling blocks” for murdered Palestinians.

Many German intellectuals and populist politicians “have adopted the European trend that demonizes Israel and repeats the Palestinian victimization narrative,” Prof. Gerald Steinberg, head of the Jerusalem-based NGO Monitor research institute, told JNS.org.

This also extends to education. A study published in June by a joint Israeli-German commission, reported by the daily newspaper Tagesspiegel, showed that some German school books present an image of Israel as an aggressive and warmongering country. The books that were examined made partisan representations of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and included “tendentious and one-sided photographic presentations” of Israeli soldiers inflicting violence on Palestinians, among other biased aspects, according to the study.

Steinberg explained that for some Germans, “the image of Israelis as ‘war criminals’ like the Nazis offsets the unimaginable horror of the Shoah (Holocaust), and of German guilt and moral responsibility.”

Back in 2011, the German Holocaust foundation Remembrance, Responsibility, Future (EVZ) was shown to have financed student exchange programs in which Israel was equated with the former East Germany and its repression, and through which students published controversial cartoons of Jews.

EVZ also financed a program at an Anne Frank School in which a Holocaust survivor told students that Israel is a “criminal state,” NGO Monitor revealed. In such cases, said Steinberg, those seeking to manipulate students “use a fringe [anti-Israel] Jew or Israeli… as a fig leaf.”

Additional evidence for this phenomenon came in a January 2015 survey by the Bertelsmann Foundation, which revealed that 58 percent of Germans said the Holocaust should be left in the past. Forty-eight percent said their opinion of Israel is poor and 35 percent said they see Israeli policies toward the Palestinians as equal to the Nazis’ policies toward Jews. The latter figure was 30 percent in a similar study in 2007, the Times of Israel reported.

Peter Ullrich, a sociologist at Technische Universität Berlin (Technical University of Berlin), told JNS.org that “for people who need national identification as a source for personal wellbeing and pride, and on a collective level for the ‘nation’ while pursuing its interests, being confronted with [that nation’s own] crimes is always a moral threat.”

In Germany, “two extremes of handling this specific German post-fascist situation have developed and often compete with one another or co-exist,” said Ullrich. On the one hand, there is a tendency to “strongly identify with the [Holocaust’s] victims or with those perceived as their equivalent,” he said.

This mindset may help explain the German government’s construction of memorials and holding Holocaust commemorations, paying reparations to the victims and their descendants, as well as the government’s condemnation of anti-Semitism. It can also serve to elucidate Germany’s tendency to officially support Israel, with Chancellor Angela Merkel saying in May that her country has a “special obligation” to do so.

But this type of discourse can be “morally ambiguous,” Ullrich said, because it has sometimes resulted in people “turning around anti-Semitic prejudice into the opposite” by taking a stereotype like the Jewish haggler and converting it into a positive image like a “very good businessman.”

On the other hand, there is “the so- called post-Holocaust anti-Semitism, which downplays or denies German guilt,” according to Ullrich.

“Both options result in the same: they seem to prove that you’re on the good side” and “serve a purpose for those who campaign for it,” yet they also “deny complexity,” he said.

In a 2013 scholarly paper titled “Antisemitism, Anti-Zionism and Criticism of Israel in Germany,” Ullrich explained that beginning in 1960s Germany, “the [political] left demonized Israel, often equating it with National Socialist Germany.” But today, he wrote, “we only find traces of such hatred” on the “very fringes” of the left.

NGO Monitor’s Steinberg cited some politicians from Germany’s Green Party and Die Linke, as well as German far-left members of the European Parliament, who have promoted the analogy of Israel to the Nazis. But other politicians, such as Green Party MP Volker Beck, have strongly opposed that comparison.

These days in Germany, in between the pro-Israel camp and the anti-Zionists at both ends of the spectrum, there is a moderate societal majority that tends to criticize both Israel and the Palestinians, Ullrich told JNS.org.

Ullrich also warned against the tendency to trace all criticism of Israel to latent guilt over the Holocaust.

“To remember the Holocaust is necessary, and there is no excuse for denying or downplaying or getting rid of remembering it. There is much proof that some people play that out by bullying Israel,” he said, but added that “the whole discursive field is much more complex” and that criticism of Israel can have different roots.

Yet according to Austrian-born Holocaust and anti-Semitism scholar Dr. Manfred Gerstenfeld, the phenomenon of “Holocaust Inversion” is more widespread in Germany than meets the eye. In a recent op-ed for Israel National News, Gerstenfeld wrote that manipulation of the Holocaust narrative has become “a mainstream phenomenon in the European Union,” and that specifically in Germany, a number of studies such as the Bertelsmann survey have demonstrated “the presence of large numbers of Holocaust inverters.”

Another such study, conducted by the German Social Democratic Friedrich Ebert Foundation, showed that in September 2014, 27 percent of Germans agreed with the statement, “What Israel does today toward the Palestinians is no different than what the Nazis did toward the Jews.”

Benjamin Weinthal, a fellow for the Foundation for Defense of Democracies think tank, wrote in a Jerusalem Post op-ed this month that German Holocaust memorials have taken “bizarre new directions.”

“Like other Holocaust memorials, the Stolpersteine project also functions, one can argue, as a kind of phony resistance to Germany’s Nazi past. … There are no memorials in Germany for Palestinian, Hezbollah and Iranian lethal anti-Semitism committed against Jews and Israelis. When an attempt was made years ago to show Israeli victims in train stations, there was an uproar and the plan was quashed.”

The trend, he wrote, marks a “fitting update” to the famous sarcastic quote from Israeli psychoanalyst Zvi Rex that “the Germans will never forgive the Israelis for Auschwitz.”