Two weeks ago, we considered Rav Shizvi and suggested that his rabbinic karet (cutting-off) was no joke, but reflected his teacher, Rav Chisda’s approach, by which rabbinic law has standing on a biblical level. A small piece of that discussion was Rav Chisda’s interpretation of Rabbi Yossi in a mishna, so we will now consider that sugya in greater detail.

The mishna (59a-b) declared various matters instituted because of darchei shalom, the ways of peace. A small subset of these are: (A) Animals, birds and fish caught in traps are not technically acquired by the trapper. Also, even if they are merely being caught in the trap, until he takes physical possession, this still prohibits someone from taking them because of darchei shalom. (B) Technically, a deaf-mute, imbecile and minor lack the intellect required to effect an acquisition, so if they find a lost item, someone else might grab the item from them, if not for darchei shalom. (C) Technically speaking, if a poor person—gleaning olives atop an olive tree—shakes the branches so that the olives fall to the ground, he hasn’t acquired them until he physically takes them in his hand, so someone else might grab them, if not for darchei shalom. For this subset (A, B and C), Rabbi Yossi—a fifth-generation Tanna—argues that these are gezel gamur, absolute theft, rather than mere darchei shalom.

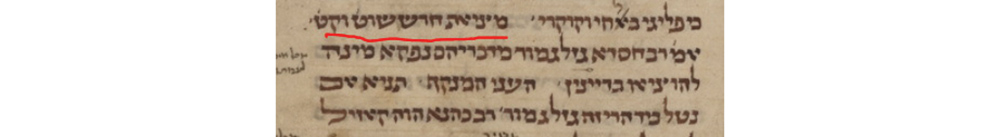

This section of mishna is analyzed in Gittin 60b-61a. Three piskaot (A, B and C) appear. Piskaot are Geonic-era citations of the mishna, which tell us which Amoraic or Savoraic statement accords with which portion of the mishna. (A) The Talmud narrator states that the Tanna Kamma and Rabbi Yossi agree regarding nets and woven traps (that it’s absolute theft), only disagreeing regarding fishhooks and other traps. (B) Rav Chisda’s statement, גָּזֵל גָּמוּר מִדִּבְרֵיהֶם, that gezel gamur means “rabbinically.” (As Rashi explains, even Rabbi Yossi doesn’t maintain it’s biblically prohibited.) The Talmudic narrator gives the distinction (between darchei shalom and rabbinic absolute theft): one can recover the money by appealing to judges. (C) תָּנָא—a baraita which elaborates on a mishna—that if the pauper gathered in his hand and placed on the ground, grabbing this, certainly, is gezel gamur.

At least, that is how we have it in our printed texts and in every manuscript on Hachi Garsinan, with the piska for B referring to the cheresh, “shoteh vekatan.” However, Maharam Schiff writes that he believes this to be a scribal error. The piska should simply quote Rabbi Yossi that “it’s gezel gamur.” This would then associate Rav Chisda’s comment with segment A—aligning with how the Rif and Rosh quote and understand it—as referring to traps.

Rav Chisda’s Scope

We might wonder whether Rav Chisda’s statement—ascribing a rabbinic level to Rabbi Yossi’s gezel gamur—only applies to case B. After all, Rabbi Yossi uses the same term, “gezel gamur,” in A and C. The piska (ignoring Maraharam Shiff, Rif and Rosh’s girsa) seems to restrict it to B. Also, the Talmudic narrator in A asserts that the Tanna Kamma agrees regarding nets and woven traps that it is gezel gamur. Conversely, Rav Chisda is an Amora while the piskaot are Geonic, and the Talmudic narrator is Stammaic. Still, the baraita in C asserts that prior to gathering it in his hand converts it to gezel gamur for the Tanna Kamma. The implication is that, the Tanna Kamma is agreeing to a biblical gezel gamur.

Related to this is the fundamental dispute (Yevamot 89b) between Rabba and Rav Chisda. Rav Chisda maintains that rabbinic law has standing on a biblical level. For instance, a rabbinic decree would return produce to a tevel state (lest he be negligent and not separate terumah a second time); a rabbinic mamzer can marry a biblical mamzeret. If the Sages empowered a cheresh to acquire on a rabbinic level, or the traps to acquire for the trapper on a rabbinic level; then, it could be deemed theft, even biblically, מִדִּבְרֵיהֶם.

Parallel Sugyot

If this statement results from Rav Chisda’s unique approach (and, perhaps, that of Sura academy, against the Pumpeditans), then we might understand why this understanding of Rabbi Yossi had to wait for a third-generation Babylonian Amora to utter. But then, perhaps, other Amoraim would dispute it!

Let’s consider parallel sugyot: In Bava Metzia 12a, Shmuel explains why a minor’s acquisition belongs to his (or her) father, implying (for the Talmudic narrator) that he doesn’t acquire by Torah law, yet elsewhere rules like Rabbi Yossi regarding a minor gleaning after his father—implying that the minor acquires, and by Torah law. The Talmudic narrator then contrasts this with our mishna in Gittin, where Rabbi Yossi declares seizing a minor’s find to be gezel gamur, and also quotes Rav Chisda, that it is on a rabbinic level. This leads to (the two Pumbeditans) Abaye and Rava’s interpretation, working with a minor’s acquisition on a rabbinic level.

Likewise, in Shavuot 41a, the Talmudic narrator tries to determine the practical difference between debt owed according to Torah and rabbinic law. The first suggestion was that we enter the debtor’s property to collect. But, the Talmudic narrator then cites Gittin 61a, and asks: “According to Rabbi Yossi—as explained by Rav Chisda—where the claimant on a rabbinic level can litigate in court, what is the distinction then?”

These parallel sugyot would, perhaps, answer Maharam Schiff, or else argue in favor of Rav Chisda applying to A, B and C. They also imply a general endorsement of Rav Chisda’s explanation—at least, as understood by the Talmudic narrator.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.