There is no doubt that we are in the fight of our lives. If the virus hasn’t gotten us directly, it has taken or affected someone we know. Sleeplessness, worry, terror and grief are our daily companions. As many among us, many close friends, prepare to get up from shiva alone to begin Pesach in unimaginable circumstances, others add names to our tehillim lists, and learn in the merit of a refuah sheleima for a dear relative or friend, all the while fighting against dark thoughts. Tears and prayer are with us as we beseech Hashem for rachamim (mercy). Every life that has been torn from us, or hangs in the balance, is essential; and each life has an entire world attached to it. These losses and pain cut deep, for many they cut deeper than we have ever known.

In this new reality, we must take comfort that the heroes among us are numerous. Our rabbis and heads of schools, who shut down our shuls and yeshivot weeks ago to make social distancing an absolute necessity, are heroes. They have saved more lives than we will ever know. These same rabbis are risking their lives—while keeping to extremely strict social distancing guidelines—to conduct private funerals as well, to honor those who passed away when we cannot. They are doing chesed for us and on our behalf, that we will literally never be able to repay.

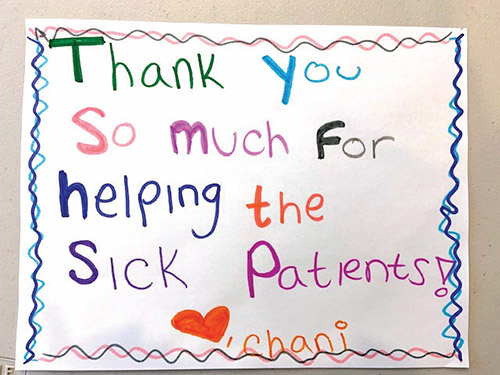

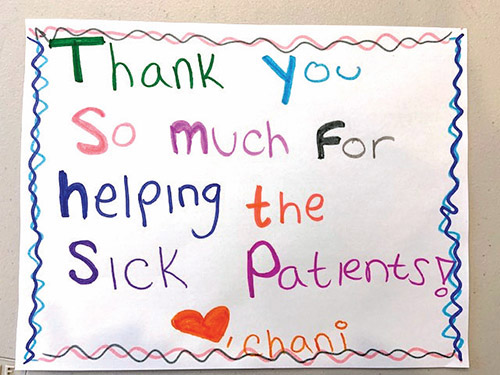

The heroes, also, are our civic leaders, doctors, nurses and the staff of our hospitals and grocery and drug stores. So too are the brave delivery people. To paraphrase last week’s Cedar Market ad on our back cover, not all heroes wear capes, but they are hopefully all now wearing masks and gloves. The “doordashers” are out while everyone else stays home, making sure that everyone is getting what they need. Who would ever have thought that a mailman or Amazon delivery truck man would bravely risk their lives, for people whose names they don’t even know? We have to remember that from within our narrowed worlds, these are silent giants among us who are keeping our worlds moving.

I write as Pesach approaches. I take comfort in having cleaned my own house, with only my husband and children for “cleaning help.” A bright spot is, even though we have been making seders at home for the past 11 years, the lack of other activities means our children have truly learned this year what has to be done to ready our home for the simchat yom tov. Maybe it is a small thing, but it is something for which I am grateful. Our children now understand what has to be done to welcome Pesach.

These small places we currently inhabit remind me of the dvar Torah written last week by my friend Miriam Gedwiser, a member of The Ramaz School’s faculty (“Out of the Narrow Places: Nissan 5780,” April 2, 2020), about the narrowed space that represents slavery, and the expansive feeling of the geulah (redemption) of the exodus. She wrote: “Chassidic commentators (see, e.g., Sfas Emes on Pesach, 1870) connect Mitzrayim (Egypt), to places of narrowness (metzarim). Yetziat Mitzrayim, leaving Egypt, includes being extricated from a place of narrowness, constriction, or pressure, to a place of openness and space to breathe.”

Several years ago, Rabbi Zvi Sobolofsky spoke to us in a Shabbat HaGadol drasha about what it really means to sit at the seder table and feel as though we had personally experienced Yetziat Mitzrayim, the exodus from Egypt. While I know this is part of our Haggadah, I ask now as I did then: How can we truly do this? In 2020, how can we feel that we were slaves in Mitzrayim, downtrodden and broken, and were suddenly taken out, under cover of darkness, and given our freedom?

Can it be so, that when Rabbi Akiva’s 24,000 plagued students stopped dying on Lag B’Omer, that the geulah of Yetziat Mitzrayim was, in Rabbi Akiva’s time, somehow comparative to what the redemption and rebirth of their community felt like? Will it be, when a vaccine against COVID-19 is made available to us, and we are able to again daven b’tzibbur, and dance with and kiss our Torahs and hug one another, that we will more completely understand the sweetness and joy of our ancestors’ exodus? And, if the Gemara of Megillat Esther, which explains Hashem’s placement of Esther in her position as queen for the specific purpose of saving the Jews of Persia, then we extrapolate that Hashem engineers our world’s solutions before the problems are visible to us? If this is so, the solution from our current predicament will present itself at Hashem’s determined time, and for that we can feel joy. The question is not if, but when.

In Talmud Brachot 5a, which I learned with my husband on Sunday, in the merit of a refuah sheleima for our friend Chana Dina bat Chava, the rishonim discuss why righteous people suffer. Rabbi Shimon ben Yochai teaches that Hashem gave three gifts to Israel, all of them given through suffering: The Torah, the land of Israel and the World to Come.

In some parts of this gemara, the word suffering is compared to the effects of salt. According to Pnei Yehoshua, “Just as salt removes impurities from meat and renders it for its intended purpose, so too suffering purifies the soul and renders it fit for the World to Come.”

May it be the case that the afflictions we feel now will purify our souls, and that the souls we have lost will enter the World to Come with no further punishments or suffering. We pray that the exodus we revisit on seder night will be a true simcha in line with a greater understanding of what it means to be free from affliction and torment; to be granted the gifts Hashem gave us, free of afflictions in all its forms.

By Elizabeth Kratz