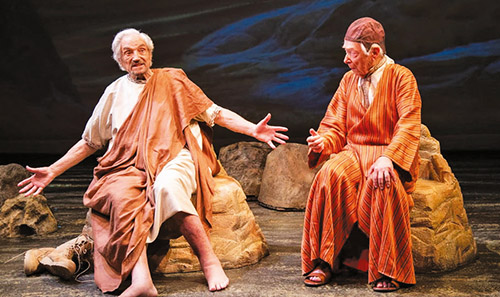

They’re bright, talented, and exceptionally funny—also unpretentious and famous, which is not an oxymoron here. Actors Hal Linden and Bernie Kopell, who are 91 and 89, respectively, star in Two Jews Talking, written by Ed Weinberger and directed by Dan Wackerman. It runs at Manhattan’s Theatre at St. Clement’s through October 23. Linden and Kopell are consummate professionals–and “heimish,” so our Zoom session is more a genial conversation than an interview.

Linden may be best remembered for his title role in the long-running television series Barney Miller, preceded by a distinguished stage career that includes a Best Actor Tony Award for his portrayal of Mayer Rothschild in The Rothschilds, with roles in The Bells are Ringing and Anything Goes. Kopell starred as “Doc” Adam Bricker during The Love Boat’s 10-year run and as a recurring character on Get Smart and other popular television shows.

I ask about their upbringing and if and how Judaism shaped their lives. Both men have deep New York Jewish roots and were raised in traditional, kosher homes. Their mothers lit Shabbos candles; for Linden’s father, Jewish identity was more tribal than religious. “He was a two-day-a-year Jew,” but such an ardent Zionist (a founder of the Order of the Sons of Zion, now Bnai Zion) that the family’s living room was off limits to his son, used only for the group’s meetings or landsmanshaft. Linden’s connection to Israel, like his father’s is unwavering; for the past 20 years, as JNF’s spokesman, he’s made multiple trips to Israel. JNF recently created a tribute video for his 91st birthday (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UrPCUaTrTSM).

Linden’s neighborhood and upbringing was, as self-described, “provincial,” with one-third each of Italian, Irish, and Jewish–but no minority–residents. There was, he remembers, a very short walking radius beyond which one “fell off” the earth. Kopell lived on Ocean Parkway, near Church Avenue. Later, the family relocated near Sheepshead Bay, and entered a less provincial but antisemitic world, one where “the bad guys…had a swell time” roughing up yarmulka-wearing boys in the synagogue lobby. The Kopells moved back to Ocean Parkway, where his father, a member of Flatbush Jewish Center, had always raised money for Israel. His loving reminisces of his mother and her delectable chicken contrast with Linden’s humorous description of his mother’s “gedempte” cooking.

Did their parents, like most Jewish parents, prioritize education? Yes, Linden emphatically affirms. College was a given in his musical family. The only question was, “which instrument?” In high school, as a professional clarinetist, he dreamed of leading a Big Band. After graduation, he became Hal Linden; Harold Lipshitz, bandleader, didn’t have quite the right ring to it. Linden studied music at Queens College and later business at City College. He began acting during his Korean War days, when he performed in skits and musical numbers, and his career took off after discharge because the Big Band era had ended.

Kopell, in contrast, cut his acting teeth while attending Erasmus Hall High. His teacher’s encouragement helped him choose acting rather than his father’s jewelry business. He graduated NYU, served in the Navy just after the Korean War, and prepped sailors there for the GED. He’s gratified, he says, that some of “the boys” graduated high school and were reading.

Had either man experienced antisemitism in the military at that time, it wouldn’t have been surprising. Linden, though, answers “not really,” because he was already Linden. On Kopell’s battleship, a rabbi conducted services. “They made a synagogue on Shabbos. So that was very sweet.” He laughs, “forgive me, Rabbi, if I say this,” and he laughs again, “but I ended up being a deacon for the Catholic Church…the last thing I did before I came here…I played a Catholic priest on Grey’s Anatomy…my Jewish friends, believe me, I am not about to convert, Okay? I’m going to remain a Yid.” We laugh.

Did they have to downplay Judaism in their careers and public personae? Kopell describes playing a nice Jewish boy on the Marlo Thomas Show concurrent with portraying a miserable Nazi on Get Smart. “I never found the humor in Nazis…” he says, and segues to an anecdote about Mel Brooks, Get Smart’s creator. Brooks came to the Get Smart set and said, “Bern, you got any kids?” Kopell answered, “No, not yet,” to which Brooks barked, “Read the Manual! Read the Manual!” “Now I got kids,” Kopell added, and we all laugh again.

Linden never experienced antisemitism, and “certainly not in the theater. As a matter of fact, I probably did it to myself, in terms of self-identification,” referring to his role in the The Education of Hyman Kaplan, about Jewish immigrants in America, in which he played the villain. “But I guess I did well enough…” because after that, a string of Jewish roles, beginning with Mayer Rothschild, followed.

I read aloud an excerpt from Sander Vanocur’s 1977 interview with Barney Miller producer Danny Arnold (https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1977/02/23/why-no-jewish-heroes/efe549da-2c63-4d2c-9b6c-8ebb15403bcc/) on the lack of on-screen Jewish heroes, largely attributable, Arnold maintains, to powerful Jews in in television and film, Linden remarks, “Well. certainly, Jewish antisemitism is classic. Jewish self-hatred is classic.” Arnold references producer Harry Cohn, who refused to hire actors with Jewish names. Linden surmises that Cohn worried that his majority non-Jewish audience would not accept Jewish heroes, “and that pervaded Hollywood for ages—that attitude.”

Arnold, Linden maintains, hired him for Barney Miller straight out of The Rothschilds. When Linden asked him why, Arnold said that “he wanted to give Barney a sense of Talmudic justice, that is ‘there but for the grace of God knows what go all of us, so that there’s respect on both sides of the table, not only the cops but the perps, and that was his intention all the way through. But Danny was a pioneer, if you will. Other producers, creators would have not gone in that direction, that’s for sure.”

Kopell explains, “I like to generalize this. In our funny business…you may not have any hint of ethnicity, whether it was Jewish or Italian or anything else…heads of studios would have people change their names…” (e.g., actor John Forsythe a.k.a Freund) or lighten their hair, as with Danny Kaye.

And today, do they feel identifiably Jewish characters, stereotyped or not, are accepted? Both men see change. Kopell begins, “Mel Brooks has made a whole different world featuring Jews—Jews, Jews, Jews. When Brooks got one of his awards, he said, ‘Behind me you can see a phalanx of Jews.’ Linden remarks that we’re not talking about Jewish immigrants anymore, and by the third generation,“…whether you like it or not, the process of assimilation has taken its toll on the Jewish community, and it’s now looked upon, I suspect, as part of the establishment.” I don’t challenge this.

“The idea of Jews playing Jewish characters,” Linden continues, “We’re stuck in a bind here…the whole thing about non-Latinos playing Latinos in West Side Story…but if we’re limited to play our own ethnic types, our own ethnic characters, I wouldn’t have played a hundred different roles…if Morgan Freeman can play King Lear, why can’t a Catholic play a Jew or a Jew play a Catholic? It’s always been a problem.”

Our discussion switches to their current show, Two Jews, Talking. There seems to be, I note, a thread connecting one act and one period (Jews wandering the desert) to another (Jews in the Millennium). Kopell is the straight man/traditionalist, more grounded and accepting, and Linden is the sceptic/agnostic. The tensions and character quirks that distinguish them make them both comic–and poignant.

Despite the disparity in the characters’ nature, Linden’s character in Act I follows Kopell’s back to Moses and the community and in Act II, his modern-day counterpart takes a yarmulka from his acquaintance. They recite Kaddish for their relatives, together. When I mention how moving this is, and that it brings out the pintele Yid in the skeptic, Linden adds: “The play is also about friendship, and personal bonding…I suspect that may be more of what the play is about…more the motivation…the acceptance or the joining in on the prayers…than being a Jew—although, he knows the prayer. He probably said the prayer many times for his parents, but ever since his wife died, he kind of lost his faith.”

How does Kopell elicits the comic aspects without stereotyping and balances the poignance? Did he have any models? “Well, my career has been a lifetime of comedy…accent after accent…” He praises Sid Caesar, master of accents, writing team Carl Reiner, Mel Brooks, and others for their brilliance. “So you either have an ear, or you don’t.”

Linden has left for an appointment, so only Kopell hears my compliment. “You had beautiful characters…they were really funny… and the way that you related to this guy who was going to go off the rails was amazing.” He continues his praise of Sid Caesar’s brilliant team “Jews are outstanding in comedy…not that other people don’t do comedy, but there’s a lot of Jews in comedy.”

In Two Jews Talking, these down-to-earth veterans of comedy, candid and forthright, carefully craft their characters and imbue them with a humanity that transcends time, challenges, and locations. Hal Linden’s and Bernie Kopell’s Jewish creations, whether skeptics or believers, are caught up in the larger reality of a shared heritage and the ability to see humor even in adversity. Onstage and in real life, when these two Jews get talking, that heritage and their humor are what keep them vibrant and there for each other.

Rachel Kovacs is an adjunct associate professor of communication at CUNY, a PR professional, theater reviewer for offoffonline.com—and a Judaics teacher. She trained in performance at Brandeis and Manchester universities, Sharon Playhouse, and the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. She can be reached at [email protected].