Our people are facing a gut-wrenching decision and an unimaginable dilemma. There are currently 116 hostages imprisoned in Gaza who have suffered through over 300 days of unspeakable cruelty and torture. They are citizens of our state, and we have a national and moral responsibility to bring them home. It appears as if the only way they can be released is through a ceasefire agreement with Hamas murderers. The only path to their release is a treaty with monsters whose hands are stained with the blood of thousands of Israelis.

On the other hand, if we don’t finish this just and moral war, these maniacs will regroup, re-entrench themselves, and recover their capacity to attack us. We have invested far too much effort and suffered far too much loss of life to leave this incredibly important job unfinished. Our survival depends upon it.

There have been countless shiurim delivered surrounding the halachot of pidyon shvuyim (redeeming captives) and how it impacts our difficult dilemma. Of course, each shiur concludes in the same manner: The conventional or typical halachic guidelines of pidyon shvuyim are not applicable to this situation. There are broader issues at play, such as, the morale of the country which would be lifted by freeing hostages after their prolonged suffering. Improved national morale is a strategic asset, especially after such a long and draining war. Alternatively, a hostage release will cause deep anguish to families of fallen soldiers for whom anything less than total victory makes their sacrifice feel hollow. The long-term effects of a hostage exchange are also frightening, as any deal will release hundreds, if not thousands, of murderers who will execute future attacks. Of course, international opinion must also be factored in as we desperately need the support of our allies, many of whom demand a hostage exchange. None of these factors appear in the Gemara in Gittin which discusses releasing captives, and these issues are similarly absent from the ensuing discussion in the Rishonim and Acharonim.

Ultimately, the sheer diversity of complicating factors renders the direct application of the halachot impossible. In 1976, when initially asked about releasing Israeli hostages held in Entebbe, HaRav Ovadia Yosef concluded that there was no indisputable halachic mandate and that the decision must be taken by military and political experts. Whatever these experts felt was best for our country would be halachically mandated. Of course, Hashem provided a miracle and liberated our hostages through the heroism of the IDF.

The very fact, however, that there are so many shiurim being delivered about the halachot of pidyon shvuyim, even though the halachot are “inapplicable,” reflects a broader phenomenon. We are becoming more committed to halachic observance but less sensitive to employing non-halachic reasoning. Our default and sometimes only response is halachic assessment. Sometimes halacha has little to say and we must apply different analyses.

Halacha-ization of Religion

Over the past several decades, halachic observance has, b”H, spiked in the Orthodox community. More people are keeping halacha more strictly than in previous generations. In part, the stiffening of halachic standards was a reaction to the rupture in our mesorah caused by 19th and 20th century secularization and by the Holocaust. Professor Chaim Soloveitchik claimed that, traditionally, halachic information was delivered through a mimetic tradition whereby practices and teachings were passed down through generations by example and through oral transmission. Mitzvot and minhagim were learned through observation and participation.

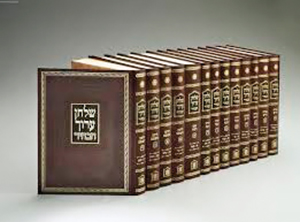

When this mimetic transmission ruptures, halachic practice is reconstructed through books and texts in a more formalized and codified manner. The widespread availability of seforim and effortless exchange of information facilitated by the internet have each contributed to the surge in halachic commitment.

Yet, primarily because halacha has been centered, other forms of religious calculus have become neglected. There are questions which lie beyond the domain of strict halachic categories. Rabbi Soloveitchik authored a landmark philosophical sefer, entitled “The Halakhic Man,” describing a religious Jew as someone who approaches life through the lens of Halacha, allowing it to shape their worldview, ethics, behavior and decision making. It was a supremely important work when first published in 1944 and articulates crucial and timeless elements of Jewish faith and practice.

However, 75 years later, it is fair to question whether we have become imbalanced “halachic men” who ignore or even stifle other forms of religious processing.

Moral Instinct

Last week’s parsha, V’etchanan, describes the value of “lifnim mishurat hadin” or preserving the moral spirit of halacha, not just the legal mandates:

ועשית הישר ו הטוב בעיני ה’

Though we are commanded to adhere to a comprehensive system of 613 mitzvot, many issues transcend the boundaries of strict halachic parameters. The value of lifnim mishurat hadin demands that we don’t just consider what we are obligated to do but also ponder what we ought to do morally and ethically. Hashem imbued us with an ethical spirit and inner moral compass, and He wants us to employ them to navigate issues which halacha doesn’t directly address.

The Flagpole and the Plumbing

Forty years ago, as a young semicha student at Yeshiva University, I walked home one wintry evening as the flagpoles high above the street were swaying dangerously in the wind. A young boy rushed over to me asking whether he had a chiyuv or a halachic obligation to notify the police. I responded that I didn’t know whether he had a chiyuv but it was certainly a good idea. Not every good idea is grounded in halachic demands.

Fast forward about 35 years, when I visited a community for Shabbat which, evidently, was struggling with plumbing complications in their shul caused by paper towels and wipes being flushed down the toilet. In response, the bathrooms were plastered with signs warning that disposing non-flushables is considered theft or gezeila as it would clog the pipes and require costly maintenance. I remember how disappointed I was that the signs implored proper behavior based upon avoiding gezeila rather than because of common courtesy and decency.

As halachic commitment has increased, the halacha-ization of Orthodox Judaism has also increased, sometimes obscuring other important forms of religious reasoning such as moral instinct and menshlichkeit.

Halacha and Geulah

This halacha-ization of Judaism has also impacted the way we analyze the redemptive process. Redemption is a new experience about which we have little tradition or mesorah to guide us. Simply defaulting to halachic concepts to process the mysteries and demands of geula is insufficient. Mori V’Rabbi, HaRav Amital, was staunchly opposed to conditioning our love for Israel and our commitment to settling the land upon the existence of a mitzvah to live in Israel (the Ramban asserts a mitzvah whereas the Rambam omits mention). Hypothetically, if there weren’t a mitzvah to settle Israel would living in Israel be less important? At this stage of history, our relationship with Israel and with Jewish history can’t be reduced to purely halachic calculus. More is demanded of us, and it lies beyond halacha.

I am similarly disappointed when the discussion surrounding Yom Ha’Atzmaut is pitched entirely around the halachot of reciting Hallel. The micro question of Hallel is important and should be analyzed through halachic processing. However, there are many who choose not to recite Hallel who still deeply identify with Israel and its redemptive potential. You cannot quantify participation in our joint historical project through halachic calculation. Navigating redemption requires different compasses. Halacha can’t always guide us. Sensitivity to Jewish history comes from our ability to hear the silent music of past generations, its gentle strains resonating within every Jewish heart and our newly established homeland.

Contraction or Expansion

The Gemara in Berachot (8a) claims that

מיום שחרב בית המקדש אין לו להקדוש ברוך הוא בעולמו אלא ארבע אמות של הלכה בלבד

After the destruction of the Mikdash, Judaism retreated into the insular study halls of Torah and the bracketed performance of mitzvot. Fortunately, Torah and mitzvot are vast, infinite and self-sufficient. For centuries, we constructed a rich and robust religious experience based solely upon that “small” but vast world of the Beit Midrash. Not only is halachic commitment foundational to religious experience but without strict and unflinching halachic observance we would not have survived, nor would we have retained our national identity. We would not have outlasted exile without passionate devotion to halacha.

Now that we have returned to Israel, even though we haven’t fully returned to a Mikdash-like state, many Jews, particularly in Israel, are experimenting with religious expression outside of Torah study and formal mitzvot. What role does commitment to land and history play within religious consciousness? Now that we live in a broader Jewish society, what role does music and art play in amplifying the Jewish spirit and, ultimately, in enriching religion— with the assumption being that the deeper the Jewish spirit the more profound the religious expression? Does our relationship with the geography and topography of our motherland impact our religious experience? People are stretching their avodat Hashem beyond halacha.

This is precisely the danger and the challenge of living in Israel, something which many who live overseas have difficulty fully understanding. Halachic observance is the cornerstone of religious experience. If it erodes religious experience, it is hollow. Searching for religious meaning outside of halacha can potentially subvert the primacy of halacha and may diminish halachic fidelity. Sadly, this has occurred. If halacha is everything, it is more likely to be strictly preserved. If there are additional voices and new expressions, there is a danger that halacha becomes decentralized.

Alternatively, if we remain limited to halachic reasoning we lack the processing tools for non-halachic issues and are incapable of stretching religious experience beyond the boundaries of halacha.

Ultimately, our challenge is to augment halacha without diminishing its importance or diluting its observance. To be “halachic men” but to go beyond. Everything must start with halacha but not everything ends with halacha.

The writer is a rabbi at Yeshivat Har Etzion/Gush, a hesder yeshiva, with ordination from Yeshiva University and a master’s in English literature from CUNY. He is the author of Dark Clouds Above, Faith Below (Kodesh Press), which provides religious responses to Oct. 7.