A nazir may not eat any part of the grape, from the חַרְצַנִּים unto the זָג (Bemidbar 6:4). But what are these? Zugt Rashi, the plural chartzanim are the kernels while the singular zag is the grapeskin. While this translation choice matches that of Midrash Aggadah, a source Rashi had just previously used, Ibn Ezra points out that this is a matter of dispute. After all, these are hapax legomena, words which aren’t found elsewhere in the biblical corpus, at least in grape-context. Often for such terms, we need to apply guesswork, based on similar roots, just the immediate context, or cognates in other languages.

The Mishna (Nazir 34b) records a dispute between fifth-generation Tannaim. Rabbi Yehuda (ben Illai) says that the chartzanim are the chutzim/skins, outsides (perhaps note the word similarity) and the zagim the seeds/seeds. Rabbi Yossi (ben Chalafta) reverses these identifications (perhaps note the singular vs. plural)—“So that you should not err, it is like a bell (zog) worn by an animal, where the outer part is called זוֹג and the inner part is called עִינְבָּל.”

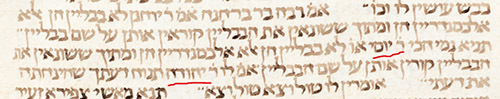

On Nazir 39a, the third-generation Amora, Rav Yosef (bar Chiyya) notes that the traditional Aramaic translation of the verse, מִפּוּרְצְנִין וְעַד עִיצּוּרִין, accords with Rabbi Yossi. (Indeed, Rav Yosef often discusses Targum.) That is, חַרְצַנִּים = פּוּרְצְנִין = seeds, and זָג = עִיצּוּרִין = skins. This matches our Targum Onkelos. Perhaps note the phonological similarity between חַרְצַנִּים and פּוּרְצְנִין. We’ll note Targum Pseudo-Yonatan reverses this, writing מִקְלוּפִין וְעַד זַגִין, thus taking חַרְצַנִּים as skins.

The written corpus of 24 biblical books can provide insight into the meaning of biblical terms, but that records a tiny slice of what was written and spoken. We should not dismiss the validity of the spoken language of the people of Israel. Even an illiterate vinedresser and his family, and descendants would refer to the grape parts by their correct names. Indeed, common folks eating grapes may use these words in their regular speech. Even generations later, the spoken language could indicate the meaning of words. Thus, Megillah 18a (with one instance transferred to Nazir 3a) describes various unknown Mishnaic or biblical Hebrew words which the rabbis were uncertain about until Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi’s maidservant used the word, e.g. “until when will you mesalsel your hair?” to a scholar curling his hair. Thus, rabbinic Hebrew and Aramaic, while not entirely secure, can occasionally shed light on the meaning of biblical verses. We needn’t dismiss a word-sense for a biblical because we only have evidence of such usage in the Mishna or Gemara. The word-sense is less sure, but is still possible or even plausible.

Jacques Gousset was a French Protestant theologian and philologist who wrote Lexicon linguae hebraicae, a Latin dictionary of biblical Hebrew. He believed that one didn’t need comparative or historical study of the Hebrew language to understand the Hebrew Torah. Gousset defined chartzanim as nuclei acinorum, grape seeds, and zag as “cortex, cutis uvarium,” thus the grapeskin. In the zag entry, he used the Rabbi Yehuda/Rabbi Yossi argument to undermine faith in Chazal’s knowledge of Hebrew. “But the real thing, the grape, I say, and its parts, are always in the hands and in the mouth, so that the names, use, and validity of those pertaining to them, should have been retained. This admonition is useful, so that no one believes that he is submissive to them…” After all, everyone ate grapes, so how could they be uncertain of these grape-part terms?

I don’t find his argument persuasive, in terms of extrapolating from one uncertainty to general lack of linguistic knowledge. Languages evolve across time, and individual words change. Sukkah 34a has Amoraim explain how, since the Temple’s destruction, pairs of words switched meanings: chalafta and aravta (willow) transposed, with implications to lulav; trumpet and shofar, with implications for Rosh Hashanah, petorata and petora, as big and small table with implications for sale; ruminant stomach chambers of bei casei and huvlilei, with implications for kashrut; and Bavel and Borsif, with implications for get. We can add Tvi and Ayal, for gazelle and deer. In “The American Language,” H.L. Mencken discusses how Americans reversed the terms for rabbit and hare. Other terms have experienced semantic shift as well. Consider how “awful” and “awesome” initially both meant awe-inspiring, and “terrible” and “terrific” both meant inspiring.

For precise terms for which broader terms are available, must we assume that people will recall? Grape seeds are also called grape stones or pips, but what if, over time, people forget this? The grapeskin might scientifically be called the exocarp, but regular folks may call it the skin. Thus, if the meaning of words are agreed upon, or have continued their usage into the present day, then it is valid evidence. But if one word pair is a matter of dispute, we shouldn’t extrapolate and believe that Chazal never knew the meaning of words.

Shadal defines chartzanim as grapes which have already been trodden to produce wine, thus encompassing both the skin and seeds. He points to Yerushalmi Demai, בראשונה היו ענבים מרובות ולא היו חרצנים חשובות, ועכשו שאין ענבים מרובות חרצנים חשובות. The implication is that when full grapes abound, who cares about chartzanim? You can make wine. But with a lack of grapes, chartzanim are valuable, because you can make temed by steeping those crushed grapes in water. So too, Berachot 22a, Rabbi Yoshiya says he’s not liable until he sows a wheat, a barley and a chartzan in a single thrust, the intent being the grapeskin with the seed within. While only the grapeseed has the reproductive capacity, someone won’t bother to remove the seed from the skin. Zag, meanwhile, is just a seed. Shadal says his explanation thus sides with Rabbi Yehuda, and against Rabbi Yossi/Onkelos.

Shadal rejects Gousset, calling it sheker mefursam, blatant falsehood! We see from Demai that they weren’t in doubt in their usage of the term; similarly, the Jerusalemite Targumim translated according to the implication of the common language. Here is where we get to the rabbinic biography part of it. Shadal suggests that Rabbi Yossi, who was born in a country which didn’t preserve their Hebrew language well, didn’t wish to rely on the natural common contemporary speech, and made himself clever to explain based on his own reasoning—with the people of Bavel following him, in the Targum attributed to Onkelos.

Was Rabbi Yossi was born in a foreign land? His father Chalafta was prominent in Tzippori (Taanit 16a) and interacted with Rabban Gamliel of Yavne in Teveria (Shabbat 115a). Actually, he was born in Tzippori. Still, he once violated a Roman decree and fled to Asia Minor. Also, Mishnayot describe crude practices of Babylonians, namely plucking at the scapegoats hair to encourage it to go (Yoma 66a) or eating the goat-chatat meat raw (Menachot 99b), Rabbi Yehuda says these were actually Alexandrians, and Rabbi Yossi says “you have comforted me.” This at least suggests Babylonian familial ancestry for Rabbi Yossi, so Shadal has ground upon which to stand. However, the respective printed sugyot actually contradict each other regarding the identity of comforter and comfortee, presumptively as a scribal error as both can be shortened to R”Y. And manuscripts of Yoma, e.g. Rab 1623 and Munich 6, have Rabbi Yehuda as comfortee, matching Menachot. Thus, we could instead ascribe Babylonian ancestry to Rabbi Yehuda, diminishing his linguistic surety, contra Shadal.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.