Educational research is often quite valuable. However, sometimes it seems to be a waste of time, energy and communal money. Every decade or so, “new” research directs us to fund new initiatives that didn’t work the last time they were tried, or to experiment with insufficiently proven theories. Worse still are those who publish to justify their existence as researchers or professors. Let me state at the outset that Dr. Alex Pomson and Prof. Jack Wertheimer are both highly regarded professionals who have made major contributions to Jewish education and to understanding Jewish life in America. What I fail to comprehend is why the AviChai Foundation commissioned this study in the first place.

Over a decade ago, The Memorial Foundation For Jewish Culture, under the leadership of Dr. Jerry Hochbaum, with the support of major internationally known academic figures, proposed a theory that if we could find a viable way of introducing Hebrew into the day schools and get an entire community to buy into it, it could be replicated and the Hebrew language could be restored to its rightful place in our schools.

First they commissioned scholarly studies to elucidate and expound on why Hebrew is so important to us as Jews. Then they commissioned scholarly studies to document and verify that Hebrew was in fact not a major component in our day schools. Their findings were confirmed. American Jews are tourists in their own culture. They cannot navigate the treasures and classics of our heritage, nor can they communicate in Hebrew even after 12 years in a day school.

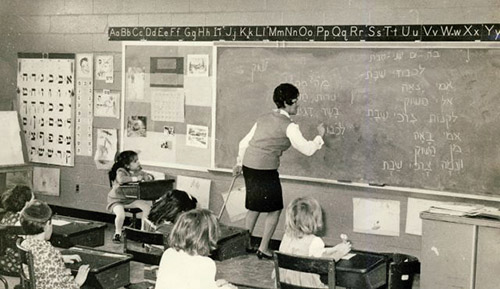

The next step was to find a community to undertake this challenge. Our community was selected because of the large number of day schools, because we had a highly regarded professional staff of senior educators (who were later re-prioritized out of existence) to carry out this task, and because we were able to convince our federation to support this project. It was a five-year grant. Without going into the technical specifics, this is what happened. We decided on several basic operating principles—teach Hebrew as a second language using second-language acquisition techniques (specifically Japanese); utilize the latest brain research on how children learn; start the project in preschool; train teachers how to teach Hebrew as a second language; and create a community of practice by bringing teachers together on a regular basis to share what works and what doesn’t work in their classrooms and to tweak the process.

The basic research and curriculum design was done by master educator Shoshana Glatzer, followed by Dr. Drora Arussy. We initially paid teachers to participate in the program. Eventually they came on their own. We took one cohort for intensive training at Ulpan Akiva in Israel, we had teleconference sessions with Israeli experts and, most importantly, we developed three separate modules of instruction depending on the teacher’s command of Hebrew. Not every native speaker knows how to teach Hebrew, and many schools do not make fluency a condition of employment, so there are varying levels that needed to be taken into consideration to make this successful. It is not enough just to teach Ivrit B’Ivrit, but there must be a well-thought-out instructional methodology.

The program also included a Hebrew-language day camp and it received additional support from The Covenant Foundation, AviChai and The Mazel Fund, and was written up in the media. We had 12 schools participating in what was called Hebrew in America. By the time children reached the first grade they were fully fluent Hebrew speakers and were helping their older siblings with their homework. The success of the program was validated in an in-depth evaluation by JESNA. The teachers loved it, especially the veteran Israelis in the group. They learned that there were very specific techniques to use to teach Hebrew as a second language.

So, what happened? After five wildly successful years, the grant funding ran out. Teachers begged for more, yet the schools were unwilling to share in the expense of maintaining the program, which included ongoing training and mentoring. Simply put, Hebrew language proficiency is not important. Not all schools require it of teachers and many native speakers are not trained to teach Hebrew. Some schools may have Ivrit B’Ivrit in the lower grades but it becomes difficult to find teachers who can teach in Hebrew in the upper grades. This problem exists on many levels. I have had extended conversations with the president of Yeshiva University and the dean of the YU’s Azrieli School of Education. Why, I asked, was it possible to graduate college with a major in Jewish education or Jewish studies, or get an advanced degree in Jewish education, without being proficient in Hebrew? The answer was that the schools don’t require it. The question remains—who sets the standards?

The schools and Hebrew-speaking camps of the previous (i.e., my) generation are no more. The current crop of school leadership may not have been exposed to the Hebrew-speaking teachers who came here following World War II. Hebrew is or should be our national language as a people. It’s the language of our sacred and non-sacred Jewish literature. It connects us to our past. Somehow it didn’t make the priority list. The shamash of a large shul was feted on his retirement after 50 devoted years of service. He remarked that when he first came here we were still the am hasefer, the People of the Book. Israel and Zionism soon became priorities and we are now am ha’aretz. He sat down to thunderous applause.

The problem is easy to solve even without funding. Just do it! Hebrew immersion (even without training) will work if it is consistent. Some schools do it. Most do not. School administrations are responsible to their boards, who in turn are responsible to the parent body. Lab School founder and great educational philosopher John Dewey wrote in “School and Society”: “What the best and wisest parent wants for his child, that must we want for all the children of the community.”

By Wallace Greene

Dr. Wallace Greene was the director of UJA’s Jewish Educational Services for over a decade. He and Shoshana Glatzer piloted the Halav UDvash preschool Hebrew program.