A Baker’s Dozen Occurrences

Who is Kedi? This sage is offered as an alternate attribution in several sugyot, such as Yevamot 90a:

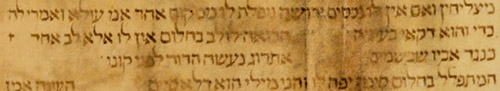

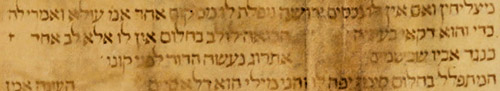

וְאָמַר רָבָא וְאָמְרִי לַהּ כְּדִי חַסּוֹרֵי מִיחַסְּרָא וְהָכִי קָתָנֵי, ““:And Rava said, and some say Kedi: The brayta is deficient, and this is what it means to say..” Kedi appears eleven times across the Talmud, though never as a standalone sage: Bava Metzia 2a; Yoma 44a, 72b; Moed Katan 19a; Megillah 2b; Horayot 8a; Chullin 73a, 81a, 118a; Gittin 54a, and Yevamot 90a.

Rabbi Yechiel Heilprin, in Seder HaDorot, cites Halichot Olam of a twelfth instance, “Ulla said, and alternately Kedi” in the ninth chapter of Berachot. Heilprin says it’s not found, but I discovered it in Berachot 57b: “If one sees myrtle in a dream, it indicates his property will prosper, and if he doesn’t own property, that he’ll inherit property. Ulla said, and some say it was taught in a brayta, וְהוּא דַּחֲזָא בְּכַנַּיְיהוּ, that this is only when he sees them on their stem.”

It is slightly strange, though not impossible, for a brayta to be in Aramaic. The Bologna text replaces בְּמַתְנִיתָא תָּנָא with וְאָמְרִי לַהּ כְּדִי.

There’s also Nazir 2a. Perhaps they missed it because it’s וְאִיתֵּימָא כְּדִי instead of וְאָמְרִי לַהּ כְּדִי.

Sage or Nobody?

Heilprin also notes that Beer Sheva (on the Horayot instance) says that Rashi frequently explains Kedi as a Sage’s name, and others explain that the Talmudic statement stated it unattributed, unattached to any Sage’s name. (So too Chochmat Shlomo on the Bava Metzia instance.) Heilprin says that Rashi doesn’t actually state this in any of the eleven instances.

The Chida (Ayin Zocher) notes Gittin 85b, where Abaye states that, in a bill of divorce, one should extend the vav of כַדּוּ so it shouldn’t resemble a yud and be mistaken for וּכְדִי, meaning “nothing”. Rashi there writes וכדי כלומר בולא כלום באין ספר כמו כדי נסבה וכמו ואמרי לה כדי שם חכם, and suggests that these words are not from Rashi. Indeed, I’d say that the point of that Rashi is that it means “nothing”, so שם חכם contradicts this, and must be a scribal error. I’d suggest that reading Chochmat Shlomo in context, his intention is that for weird or otherwise unknown names, Rashi often suggests this as a שם חכם, rather than saying Rashi explicitly says it about Kedi.

Kedi Throughout Talmud

I agree that Kedi means lack of attribution. If he were a Sage, we could try to place him temporally and geographically based on who he interacts with, and find out if the imposed constraints were consistent in all dozen cases. Instead, we’ll explore a few of the interesting occurrences and consider what may have prompted them.

In Bava Metzia 2a, the Mishnah gives “two cases” where two are grabbed onto a tallit, each claiming (a) I found it and (b) it’s all mine. The opening sugya is deeply Stammaic, from the Talmudic Narrator, finally establishing via argumentation that (a) and (b) are separate claims, rather than a compound claim. Immediately following is: אָמַר רַב פָּפָּא וְאִיתֵּימָא רַב שִׁימִי בַּר אָשֵׁי וְאִמְרֵי לָהּ כְּדִי רֵישָׁא בִּמְצִיאָה וְסֵיפָא בְּמֶקַח וּמִמְכָּר. (“Rav Pappa or alternatively Rav Shimi bar Ashi (both fifth-generation Pumpeditan students of Abaye and Rava), alternatively Kedi, said: the first case is finding an object and the second case is purchasing.”) While there is a general interesting question of the relationship of Rav Pappa to the Stammaitic text, at issue here is whether fifth-generation Amoraim are subscribing to the Stamma’s separate claim theory, or whether the Stamma himself elaborates on the theory.

Here, I believe Rav Pappa / Rav Shimi bar Ashi did say it, but their (a) case is where the disputants have seized a tallit and say the joint statement of finding it and it being entirely theirs, while their (b) case of the Mishnah is either where “one says half is mine” (for who seizes an article in order to only acquire half?) or where the disputants are riding an animal, and only say “It is all mine”. That their statement possesses a potential hidden meaning, reinterpreted by the Stamma suggests this statement earlier and Amoraic. That the redactor isn’t certain if it’s from the Stamma suggests that ambiguous attribution is a rather late redaction.

In Megillah 2b, first Rava sources the Mishnah’s law that those in cities walled since Yehoshua bin Nun’s time read on the fifteenth. Although the preceding verse explicitly mentioned Shushan celebrating that year on the fifteenth, he cites a verse about unwalled villages celebrating on the fourteenth, implicitly signaling that walled cities would read on the fifteenth. A long Stammaic passage ensues, followed by a question of Shushan itself, walled but not since Yehoshua’s time. The answer: אָמַר רָבָא, וְאָמְרִי לַהּ כְּדִי: שָׁאנֵי שׁוּשָׁן — הוֹאִיל וְנַעֲשָׂה בָּהּ נֵס. Rava, or unattributed, says Shushan is different, since the miracle occurred in it on the fifteenth. If from Rava, his statements are joined and work together, and the Stamma later interjects intervening exposition. If from the Stamma, then the Shushan case works in context.

In a previous column, Just One Rava, I discussed how some scholars mistakenly believed there was a Savoraic Rava II, since Rava seemed to respond to the Talmudic Narrator’s discussion. In truth, sugyot developed over time, and often the Stamma interjected material to prompt / frame Amoraim’s ideas, The sugyot read smoothly with only Amoraic material. This is one such case.

In Horayot 8a, it is either Rava, Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi, or Kedi, who interpret a verse about unwittingly violating all mitzvot as referring to idolatry, because idolatry weighs in importance against all mitzvot. Generally speaking, to explain alternate attribution, we should inspect the Talmudic text before and after the statement, to see if these Amoraim occur and in what context. Indeed, earlier on 8a, the Stamma refers to Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi who teaches his son that idolatry is compared to the entirety of Torah for bringing a sin offering for unintentional violation. Meanwhile, the most recent Amora who directly spoke was Rava to Abaye, on 7b.

I’m somewhat stymied regarding our Yevamot 90a sugya. A brayta declared that a kohen’s minor wife (married rabbinically by her mother/brother) eat’s terumah on his account. The gemara clarifies this refers to rabbinic, rather than Biblical, terumah. As proof (תָּא שְׁמַע), it cites a troubling brayta, which it analyzes (וְהָוֵינַן בַּהּ) and proposes and answer (וְאָמַר רָבָא וְאָמְרִי לַהּ כְּדִי חַסּוֹרֵי מִיחַסְּרָא וְהָכִי קָתָנֵי) about amending the brayta, with the new reading acting as the proof. These textual features indicate a later stratum utilizing an earlier stratum. תָּא שְׁמַע means a proof from elsewhere; וְהָוֵינַן בַּהּ means it’s citing an external, often Amoraic analysis and reinterpretation which already occurred, and וְאָמַר instead of אָמַר means that Rava (or Kedi) is also part of that external citation. Alas, I don’t know where this earlier external sugya exists. The parallel is Gittin 54a, but that also has תָּא שְׁמַע, וְהָוֵינַן בַּהּ, and וְאָמַר, so it’s not the original either. Perhaps the original disappeared.

Why would we think Rava (vs. Kedi) is the one conducting surgery on the brayta? Perhaps it’s the subsequent appearance (in Yevamot / Gittin parallel) of Rav Acha bar Rav Ikka, a fifth-generation student of Abaye. He’d then be reacting to a stratum of Rava’s (fourth) generation. Indeed, the “havayot of Abaye and Rava” are an earlier stratum with which later generations dealt. Also, חַסּוֹרֵי מִיחַסְּרָא is often asserted by the Talmudic Narrator, but occasionally by Rava or Ravina, so he’s a likely candidate. Indeed, of the baker’s dozen, six – Yevamot 90a, Gittin 54a, Chullin 73a, 81a, 118a, Nazir 2a – involve Rava vs. Kedi and חַסּוֹרֵי מִיחַסְּרָא surgery. So, for our Yevamot sugya, both Rava and Kedi work well, but without knowing the original sugya context, it’s impossible to tell more.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.