How the Temple Was Almost Rebuilt in Time for Sukkot in the Fifth Century

In the biography of the monk-soldier Bar Sawma who was active in the Land of Israel in the fifth century, it is told that Jews and Samaritans virtually governed the land and they persecuted the Christians. Bar Sawma led a campaign against this Jewish-Samaritan front, presumably with the assistance of a Byzantine army. The Jewish-Samaritan forces were said to have consisted of 15,000 armed men. The Jews were defeated and Bar Sawma describes the ensuing destruction on the Jewish towns and villages. Regarding one synagogue in the city of Reqem of Gaya (Petra), he remarks, “It could bear comparison only to Solomon’s Temple.”

In about the year 425, the Jews of the Galilee and its surroundings applied to the empress Eudocia to permit them to pray on the ruins of Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem, as they had forbidden to do so since Constantine. The empress relented. The author of the aforementioned biography cites a letter purportedly written by the Jews of Galilee to the Jewish communities in Rome and Persia:

“To the great and elevated nation of the Jews, from the Priest and Head of Galilee, many greetings. Ye shall know that the time of the dispersion of our people is at an end, and from now onwards the say of our congregation and salvation has come, for the Roman kings have written a decree to hand over our city of Jerusalem to us. Therefore come quickly to Jerusalem for the coming holiday of Sukkot, for our kingdom is established in Jerusalem.”

And indeed 103,000 Jews came and gathered in Jerusalem but they were struck by calamity where—in the biographer’s version—”big stones rained from the sky,” whereas the Jews complained to the empress that they were attacked by hostile monks.

Some historians have understandably cast doubt on the version of events cited there. Some have cast serious doubt on the stories relating to the Jews since he lived a century after the events described. Moshe Gil retorts that “this is a facile way of dismissing ancient sources. We must not disregard or refute their contents even if they appear legendary in character; they still retain a germ of historical truth.”

Culled from Moshe Gil, “Palestine” p. 3

The coin in photo 1 is of special interest and historical value. It was minted during the third and last year of the Jewish revolt against Rome (year 134/135 CE). Lulav holder with three minim and etrog on his left. Hebrew inscription around: For the Freedom of Jerusalem.

This arrangement follows (unsurprisingly) the opinion of Rabbi Akiva in the Mishna. (1)

Also interesting to note, the sort of basket that is meant for holding all the species together. This is still followed by Ashkenazim.

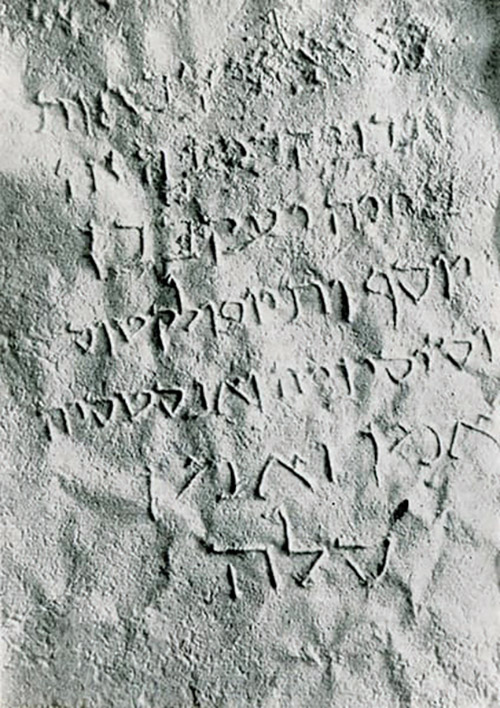

The coin in photo 2 depicts a palm tree and the legend: Elazar the High Priest. Many scholars identify him with Elazar Hamodai who was, according to the Talmud, an uncle of Bar Kochba.

What’s interesting about this coin is that the writing is in Paleo-Hebrew while R’ Elazar championed the superiority of the “modern” Assyrian script. (2)

It seems that Jewish nationalists (this is evident from Maccabean coins as well) actually deemed the older script to be more authentic—and the reintroduction of this script, at such a late date, may have been part of a nationalist revival on the part of Bar Kochba.

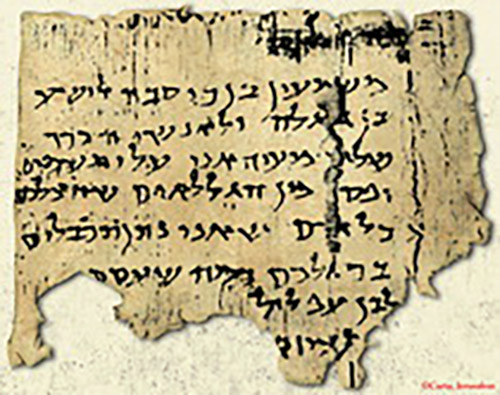

The fragment is part of a letter written by Bar Kochba to a district commander requesting the immediate delivery of four species to supply his troops for the� upcoming Sukkot holiday.

This is the text of the letter:

English:

Shimeon to Yehudah bar Menashe in Qiryath ‘Arabaya.

I have sent to you two donkeys, and you must send with them two men to Yehonathan, son of Be’ayan and to Masabala, in order that they shall pack and send to the camp, towards you, palm branches and citrons. And you, from your place, send others who will bring you myrtles and willows. See that they are tithed and sent them to the camp. The request is made because the army is big. Be well.

By Joel S Davidi Weisberger

�