I am fascinated by names, especially Biblical names. Names reveal a great deal about the beliefs, hopes, superstitions and fears of the people who bear them.

With the birth of Zionism and the first and second aliyah, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Jewish settlers in Eretz Yisrael began giving their children names that probably had not been utilized since Biblical times. For the first time in Jewish history since the days of the Bible, nice Jewish boys were walking around with such names as Nimrod (a particularly evil Mesopotamian king who some identify with Gilgamesh), Omri (another evil Israelite king), and Amatziah (an evil Judean king).

But is it true that these names (among many others) were considered non-kosher throughout Jewish history until the Zionist movement made them kosher again?

Let’s first begin with the name Nimrod and its seemingly inexplicable popularity in Israel. The following article sheds some light on that particular phenomenon.

The main founders and leaders of Zionism in the late 19th and early 20th century were mostly non-religious, sometimes anti-religious. Zionist thinkers, historians and writers reinterpreted the whole of Jewish history (including, and especially, the Bible) from a secular nationalist viewpoint considerably different from and sometimes diametrically opposite to the religious Jewish tradition.

Specifically, the search went on for past historical or mythical figures who could be depicted as national heroes, such as those that inspired the European national movements of the 19th century. Those fitting the role were often placed on pedestals even when Jewish tradition frowned upon or strongly condemned them (for example King Omri of ancient Israel, which the Bible describes as an evil idolater but which Zionists approved of as a victorious warrior king and the founder of a strong dynasty).

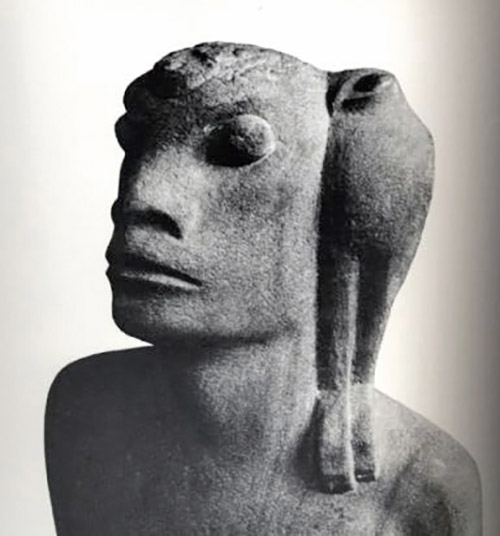

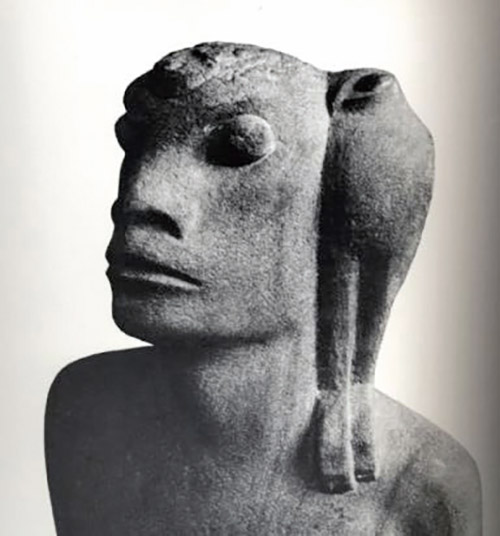

Sculptor Yitzhak Danziger, who was born in Germany and emigrated to the then British Mandate of Palestine, created his statue “Nimrod” in 1938-1939 (pictured).

The “Nimrod” statue is 90 centimeters high and made of red Nubian Sandstone imported from Petra in Jordan. It depicts Nimrod as a naked hunter, uncircumcised, carrying a bow and with a hawk on his shoulder. The style shows the influence of ancient Egyptian statues.

The unveiling of the statue caused a scandal. The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, which had commissioned Danziger’s statue, was not happy with the result, and religious circles made strong protests.

Within a few years, however, the statue was universally acclaimed as a major masterpiece of Israeli art, and has noticeably influenced and inspired the work of later sculptors, painters, writers and poets up to the present.

The Nimrod statue was also taken up as the emblem of a cultural-political movement known as “The Cannanites,” which advocated the shrugging off of the Jewish religious tradition, cutting off relations with Diaspora Jews and their culture, and adopt in its place a “Hebrew identity” based on ancient Semitic heroic myths—such as Nimrod’s. Though never gaining mass support, the movement had a considerable influence on Israeli intellectuals in the 1940s and early 1950s.

One tangible lasting result is that “Nimrod” has become a fairly common male name in present-day Israel. In the 1940s, bestowing it upon a newborn child was something of a political statement. In the present generation, however, it is taken simply as a name like any other (as English-speaking parents giving their child the name “George” do not necessarily spend much thought on the legendary dragon-slaying saint who bore that name).

An alternate explanation offered for the popularity of Nimrod has to do with the politics of the yishuv during the British Mandate. The name Nimrod, which means “rebellion,” was used as just another weapon in the Zionist struggle against British rule.

Dr. Nimrod Raphaeli, a senior editor at MEMRI, was born in Iraq in 1933. Perhaps his parents gave him the name for the reason mentioned in the article, or maybe Nimrod was an acceptable name for a nice Jewish boy living in Iraq in the ‘30s.

An article on popular Israeli given names in the Maariv newspaper in Israel also pointed out the curiosity of the name here:

המסורת היהודית הטילה הגבלות רבות על שמות שמותר לתת לילדים. כריבוי ההגבלות, ריבוי ההיתרים והחריגים. הקבוצה האסורה איסור מוחלט, כפי שסיפר החוקר חיים ריבלין, היא קבוצת הרשעים, אויבי העם היהודי, ועל כך נאמר במדרש: “וכי יקרא אדם שם בנו פרעה, או סיסרא, או סנחריב?” . ברשימת משרד הפנים של שמות שאסור לאשרם נמצאים אדולף היטלר, אוסמה בן לאדן, ודמות אקטואלית השבוע: המן. עם זאת, רשעים שונים זוכים להקלות. למשל, ישמעאל, שעשה תשובה. יש הסכמה שנמרוד, עשיו, עמלק ודואג היו רשעים, אבל נמרוד הוא כידוע שם שניתן לילדים ישראלים לא מעטים, כהתרסה למסורת היהודית

Partial translation: Jewish tradition sets limits on the types of names permissible for Jewish children. A group of names that sit “beyond the pale” and are in fact illegal according to Israeli law are: Adolf Hitler, Osama bin Laden and Haman (!). Despite this, a more liberal approach is applied to names like Ishamel (who, tradition has it, repented toward the end of his life). Although the historical figures of Nimrod, Esau, Amalek and Doeg were wicked men (at least as depicted in the Bible), Nimrod remains a very popular name among contemporary Israelis in opposition to Jewish tradition.

Looks like the editor over at Maariv could have delved a little bit more into the history of this name among Jews before jumping to his conclusion…

I came across another instance of the name; in the year 1969, 14 Iraqis, nine of them Jews, were falsely accused of spying for Israel by the Baath regime under Saddam Hussein. All of them were hanged in the public square. One of the unfortunate victims was a Jew by the name of Yaaqov (George) Nimrodi (transliterated into Arabic as Yacoub Gourji Namerdi). The names of the nine Jews are now inscribed on a stone monument (see photo) in the Israeli city of Or Yehuda, where many Iraqi Jews settled upon their arrival in the Holy Land.

In English, Nimrod has a very negative connotation. From the Dictionary of American Slang and Colloquial Expressions by Richard A. Spears, Fourth Edition, 2007:

nimrod [ˈnɪmrɑd]

n. a simpleton; a nerd: What stupid nimrod left the lid off the cottage cheese?

Controversy

In 2007, Rabbi Avraham Yosef, chief rabbi of the city of Holon and the son of former Sephardic Chief Rabbi Ovadia Yosef, came under heavy criticism after he publicized a ruling on his weekly radio show stating that people who possess such “wicked names” as Herzl (in Israel, Herzl as a proper name used to be quite common especially among Mizrachi Jews) and Nimrod must change them immediately.

It was his condemnation of Herzl that aroused the ire of many. Religious Zionist commentator Uri Orbach took issue with Yosef’s characterization of Herzl as wicked and accused him of pandering to anti-Zionist charedim.

One of the stranger recurring names throughout Jewish history is that of Yishmael. In the Bible, Yishmael is considered to be the wicked son of Abraham and is banished from his household along with his mother Hagar. In later Rabbinic tradition, Yishmael is considered to be the ancestor of the modern Arab nation.

In the Midrashic tradition, however, Yishmael repented toward the end of his life and reconciled with his brother Isaac, thus rendering the name kosher (?).

The question still remains why the name Yishmael pops up even after the rise of Islam, when the name would probably have taken on a “heavier” connotation. Yet we see at least two Yishmaels, one in 18th-century Italy and one in 16th-century Egypt. S. from the onthemainline blog opines that Yishmael was an acceptable name only among kohanim because of Rabbi Ishmael the High Priest who was martyred in circa 70 c.e. (the aforementioned two were indeed kohanim).

Joel Davidi Weisberger is an independent researcher and translator. He also runs the Channeling Jewish History group and can be reached at yoelswe@gmail.com.