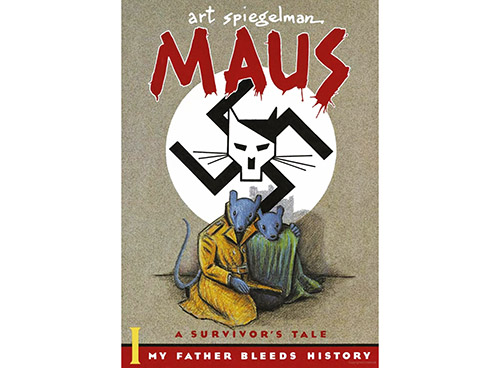

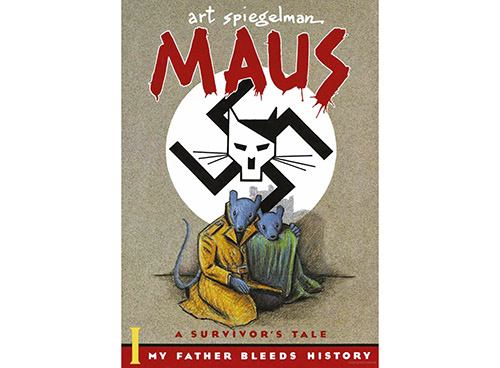

Highlighting: “Maus I: A Survivor’s Tale: My Father Bleeds History” by Art Spiegelman. Pantheon. 1986. English. Paperback. 159 pages. ISBN-13: 978-0394747231.

A teacher using the Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic comic “Maus” for the first time to instruct students about the Holocaust found the experience left a lasting impression on the young teens about the horrific consequences of dehumanizing and marginalizing others.

Caroline Guinee, who teachers freshmen and sophomore English at Summit High School, said Art Spiegelman’s depiction in his comic books of the horrors his parents experienced during the Holocaust was amplified by having the granddaughter of an Auschwitz survivor speak to students, combining to make a powerful impact on them.

“We had a lot of focus on the process of dehumanization and how that doesn’t happen overnight,” said Guinee, adding that students discussed how images of Jews being hung in broad daylight couldn’t have happened without such dehumanization.

Guinee said teaching “Maus,” although new to her, has long been part of the school’s curriculum. It was also a coincidence that she began instruction about the same time as her participation in a March 3 virtual workshop for middle and high school teachers offered by Rutgers University’s Allen and Joan Bildner Center for the Study of Jewish Life and its Herbert and Leonard Littman Families Holocaust Resource Center.

The program was led by Barbara Mann, Chana Kekst Professor of Jewish Literature at the Jewish Theological Seminary and an expert on graphic Holocaust novels written in the aftermath of the groundbreaking “Maus.”

The program was organized in the wake of the national controversy that erupted after a school board in McMinn County, Tennessee voted unanimously to ban “Maus” from its eighth-grade curriculum. The book, which depicts Jews as mice and Nazis as cats, was objectionable to the board because of the nude image of Spiegelman’s mother after her suicide, and eight curse words. The outcry pushed “Maus” to the top of national bestseller lists.

Mann cited the value of using graphic novels and comics as tools in teaching the Holocaust now that the first generation of survivors and eyewitnesses has largely passed.

Those writers, such as Elie Wiesel, “carried a sort of moral authority,” while the second generation, such as Spiegelman, have “inherited trauma.”

“In the work of the second generation we get the aftereffects and see how the aftereffects reverberate through families in the second generation,” said Mann.

Comics, which largely were the product of Jewish immigrants, have often depicted evocative drama. She explained that inherited trauma came into play with Spiegelman.

“Art Spiegelman didn’t set out to necessarily write of the Shoah or his family experience, but simply wanted to produce a long-form comic where readers would need a bookmark,” said Mann. “He wanted to write something serious in long form.”

Mann pointed out that it was important for students to understand that Spiegelman’s use of Jews as mice was a deliberate reference to the classic European depiction of Jews as rodents or vermin.

Guinee said her students were taken aback by the book’s banning and, in fact, understood and loved its message. The virtual conversation with the granddaughter of the Auschwitz survivor also seemed to parallel what students had read.

“It’s one thing to read about it, but to hear someone actually speak about it added another layer of impact,” said Guinee.

The students were not unfamiliar with Holocaust survival, having read “The Diary of Anne Frank” in eighth grade, but hearing another real story of survival really affected them.

“Afterward they were all kind of silent,” Guinee said. “They asked her questions and let it soak in. The next day, I don’t know, they seemed sort of humbled, but I could see it affected them a lot. They expressed appreciation that she was able to tell her story.”

Guinee said she would “definitely” teach “Maus” again next year and said both she and her students learned a lot from it. “We’ve had a lot of conversations about marginalization,” she said. “The students seem to be very aware of how outcast groups are treated in society.”

By Debra Rubin